Rising food prices are causing more and more people to go hungry in sub-Saharan Africa. My new research shows that an overlooked cause could be El Niño, a climate phenomenon in the Pacific that affects weather patterns globally.

Food inflation rates are between 20% and 50% in some African countries. Without urgent action to curb rising food prices in sub-Saharan Africa, millions more people face undernourishment and malnutrition, adding to the 239 million already affected. In a recent paper, I demonstrated that El Niño events can trigger increases in food prices and exacerbate food crises if other conditions, such as government policies, remain unchanged.

El Niño refers to a natural cycle in Earth’s climate centred on the equatorial Pacific Ocean. There are three phases: a neutral phase, El Niño (the warm phase) and La Niña (the cold phase). In the neutral phase, trade winds blow from east to west across the tropical Pacific, pushing warm surface water from South America towards Asia and Australia. Every two to seven years, this normal pattern is disrupted, leading to either an El Niño or a La Niña event.

El Niño events result in abnormally high sea surface temperatures in the Pacific which weaken or reverse these easterly winds, making them blow from west to east. La Niña strengthens the easterlies, resulting in cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures. The recent 2023-24 El Niño was among the five strongest on record.

Influence of El Niño and La Niña on the average global temperature since 1950

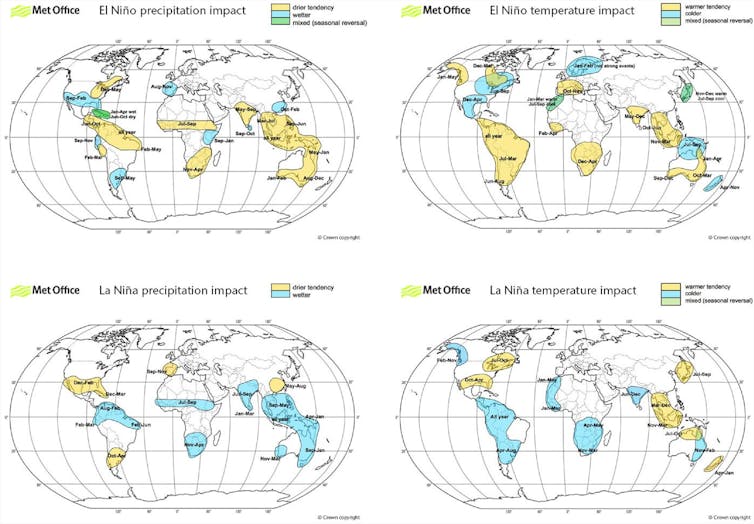

Although these events originate in the Pacific Ocean, their effects extend far beyond the region, like ripples spreading out across a pond. The 2023-24 El Niño resulted in heavy rains and flooding in eastern Africa and severe drought across southern Africa. These extreme weather conditions have damaged crops, reduced their yields and degraded the soil. The result has been significant food price rises in most of sub-Saharan Africa.

Where El Niño hits hardest

Southern, eastern, and parts of central Africa are more likely to experience significant fluctuations in the prices of staple foods as a result of El Niño. For example, the price of maize, the staple food preferred by most people in sub-Saharan Africa, doubled in South Africa and Malawi due to the El Niño-induced droughts of 2015-16 in southern Africa.

The negative effects of El Niño on food prices are amplified in countries that are already mired in conflict or political instability, such as Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Somalia.

However, I found that El Niño has a smaller impact on food prices in west Africa, where the climate is less sensitive to these events. Southern Africa’s climate meanwhile, which ranges from tropical to temperate, tends to face more significant disruption following an El Niño due to its effect on regional temperatures and rainfall.

Heat and moisture in African regions during El Niño and La Niña

The effects of El Niño vary by crop type. My study found that staples such as maize and sorghum are particularly susceptible to price increases during El Niño. A particularly strong El Niño event can cause price increases ranging from 2% to 20% for maize, with the impact being most pronounced in southern Africa.

Abroad, El Niño significantly weakens monsoon rainfall in India and Thailand, the two largest rice-exporting countries which account for more than 50% of the global rice trade. Reduced and erratic rainfall caused by the weakened monsoon can affect how much rice these countries produce.

Similar to maize, imported rice is a staple in many sub-Saharan African households. When El Niño affects yields in countries that export rice, it alters international rice prices which then affects prices in local markets of sub-Saharan Africa.

Preparing for the future

Some crops appear resilient to El Niño-induced price fluctuations. Prices of staples such as cassava, millet and local rice varieties tend to be more stable, thanks to, among other things, their deep roots that make the crops more resistant to drought. Little wonder countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo are turning to these “magic” crops to adapt to the changing climate.

Suppose historical data and trends are anything to go by. In which case, governments in climate-vulnerable subregions such as southern, eastern, and central Africa can learn from previous experiences and mitigate the impact of the recent 2023/2024 El Niño on the prices of weather-sensitive crops like maize.

At the same time, they should increase the production and preservation of weather-resistant crops such as cassava, to shore up food supplies as a La Niña event approaches. Both it and El Niño impact weather patterns in sub-Saharan Africa, causing droughts, floods and other challenges.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get our award-winning weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 35,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Lotanna Emediegwu does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.