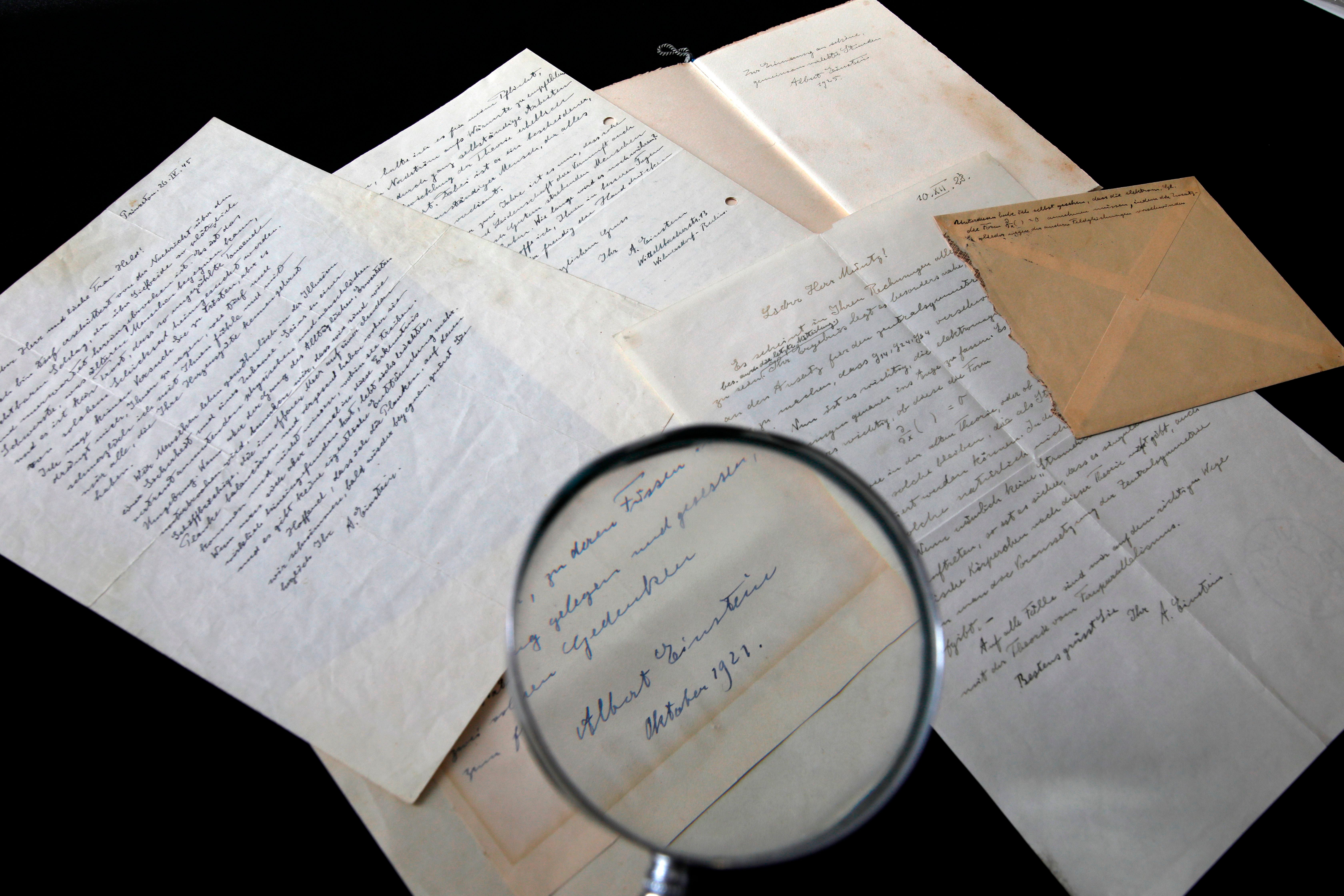

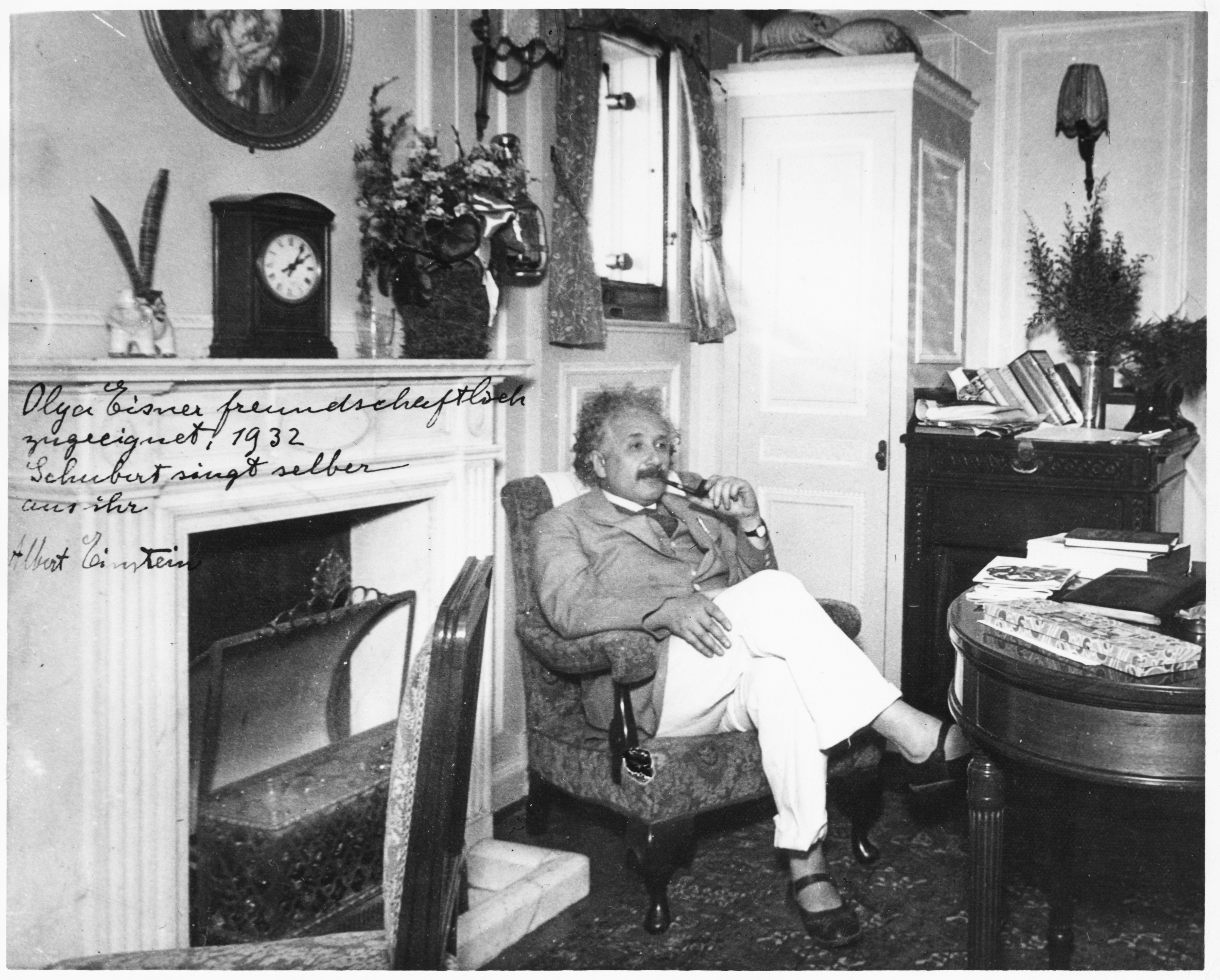

When an extraordinary cache of love letters written by Albert Einstein to his first wife between 1898 and 1903 went up for auction last December, the historic collection was expected to fetch up to $2 million.

At minimum, the Einstein letters —in which the Nobel Prize-winning physicist elucidated not only his amorous feelings for Serbian physicist Mileva Marić, but also his initial thoughts on the theory of relativity — were expected to sell for at least $1.3 million, the low estimate from Christie’s, the esteemed auction house handling the sale. The missives have been described as the “most important source for Einstein’s early life and intellectual development,” including “the only known information” about the illegitimate daughter he secretly fathered in 1902.

“I am more and more convinced that the electrodynamics of moving bodies, as presented today, is not correct,” Einstein wrote in one.

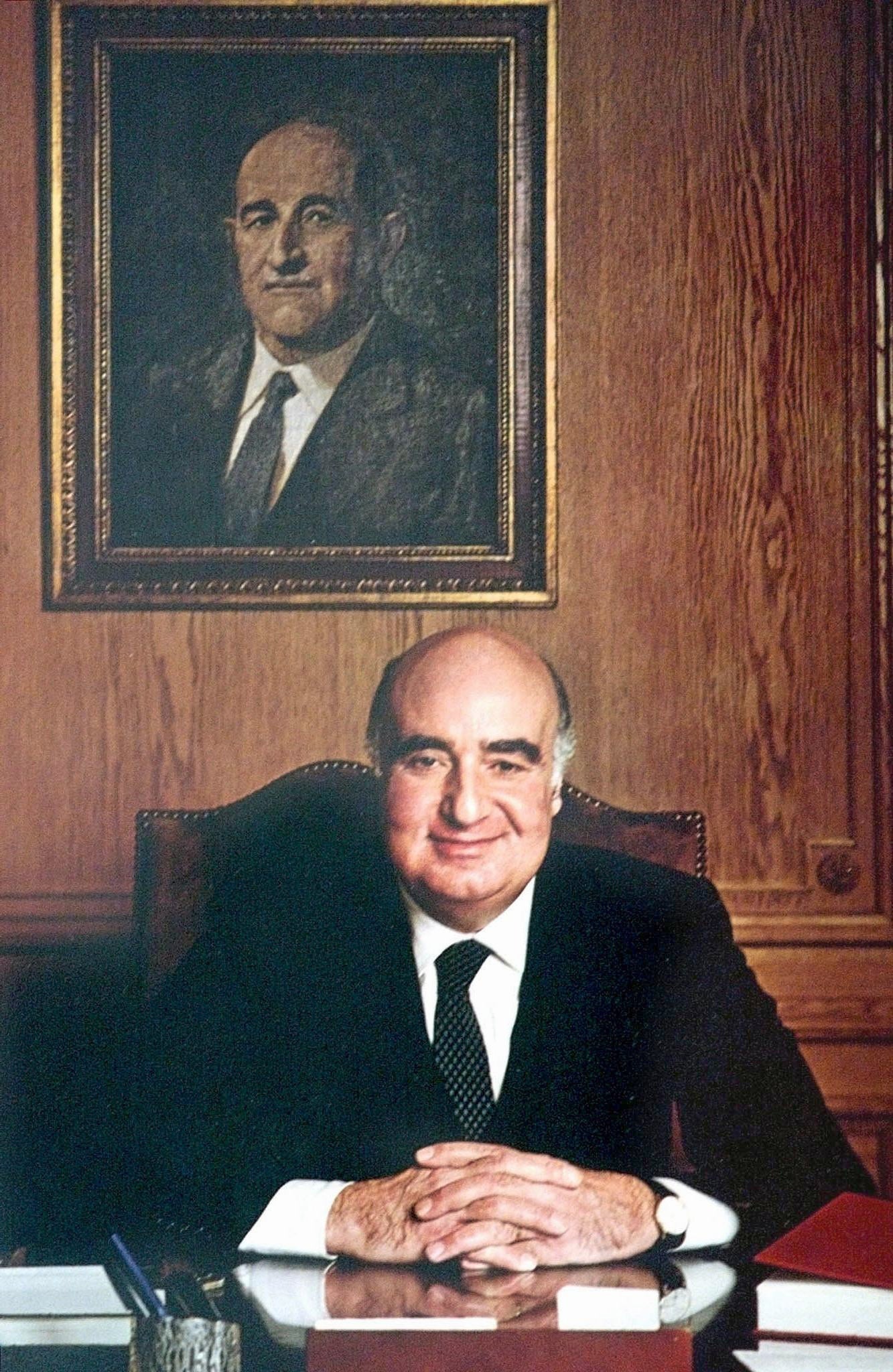

However, the lot of 55 letters brought just $430,000, a sum that deeply disappointed the previously anonymous seller, now unmasked in a tranche of legal documents obtained by The Independent as billionaire financier Jacqui Safra.

In the filings, the Encyclopedia Britannica owner, California vineyard boss, and sometime Woody Allen film producer says Christie’s did not have the right to sell the Einstein letters, and further blames the auction house for sloppily offloading them at just 35 percent of the low estimate, in what he dubs a “fire sale.”

“This is not merely a case of breach of contract,” states an affidavit filed Friday. “Christie’s actions represent a systemic betrayal of trust, wherein the world’s largest auction house manipulated its power over one of the most significant private collections of art and cultural artifacts in history.”

In an email on Sunday, Christie’s Chief Marketing and Communications Officer Gillian Gorman Round, said, “We have no comment to make on this matter.”

An application by Safra for a temporary restraining order asking a judge to halt the upcoming sale of additional artworks from his $100 million collection — $87 million of which he purchased from Christie’s — says the 78-year-old financier trusted the auction house to be a “steward” of his “unique works of unparalleled historical value.”

Instead, it alleges, Christie’s “exploited this trust,” and fabricated a “deliberate strategy to suppress the value” of the pieces by “mismarketing, undervaluing, and systematically failing to perform its contractual obligations — all while exploiting its position to siphon off fees and commissions in direct contravention of its agreements.”

The most recent example, the application says, was Christie’s bungled sale of the Einstein letters.

Safra says in the court filings that Christie’s put the Einstein letters on the auction block in spite of his objections, as they were tied to a $63 million loan he personally guaranteed, using his art collection as collateral. The items Safra pledged to secure the loan include “one-of-a-kind pieces of furniture, antiques, writings, manuscripts, and ‘Old Master’ paintings and drawings.” To ensure that the pieces would sufficiently secure the loan, Christie’s assigned expert valuations to each, according to the filings.

When Safra defaulted on the loan in 2022, Christie’s claims it was free to auction off any pieces it pleased. However, Safra argues that he had always reserved the right to decide which items would be put up for sale, and when, and that Christie’s knew he “never wanted to sell” the Einstein letters.

“Christie’s was well aware that the Einstein Letters were of tremendous sentimental value to Mr. Safra,” according to a complaint docketed alongside 28 separate court filings. “Indeed, prior to Mr. Safra pledging the Einstein Letters under the Agreements, Christie’s had approached Mr. Safra on multiple occasions to sell the letters. Mr. Safra declined each time.”

Safra claims that Christie’s, among other things, failed to put together a compelling auction catalog for the letters, failed to highlight the “scientific significance of the matters Einstein discussed in those letters,” and “failed to even state how many letters were in the lot,” according to Safra’s filings. When Safra brought up these issues, Christie’s refused to heed his warnings, he alleges.

By Christie’s purposefully letting go of the Einstein letters and other pieces at bargain prices, Safra says he has not hit certain repayment thresholds that would automatically halt the sale of additional items from his collection. Instead, according to Safra, a financially struggling Christie’s has liquidated the works collateralizing the loan at lowball prices in order to accelerate its repayment terms and creating “artificial obstacles” undermining Safra, who says he has been forced to pay Christie’s some $8 million in additional fees “not contemplated by the parties’ original agreements.”

Further, Safra claims, his missed targets allow Christie’s to continue “improperly” accruing default interest on the unfulfilled loan terms.

“The harm caused by Christie’s extends beyond financial losses,” Safra’s complaint states. “[His] collection includes irreplaceable cultural artifacts that hold historical, artistic, and personal significance. These treasures, once entrusted to Christie’s care, have been stripped of their rightful value and scattered in a reckless attempt to prop up Christie’s bottom line.”

The restraining order application seeks to halt the impending sale of 25 Old Master artworks from his collection on February 4 and 5, and several more on February 7.

In it, Safra claims there are “significant errors” in Christie’s latest catalog listings that, much like the Einstein letters, wipe out significant value from those works.

Since the first auction in January 2023 of items from his collection, Christie’s has sold 368 of Safra’s pieces, for a combined 20 percent less than its own low estimates, the application states.

He is demanding damages “equal to the difference between the fair market value and the hammer price” of the pieces sold by Christie’s, plus interest, punitive damages, plus attorneys’ fees.