People are obsessed with narcissism and narcissists. They want to know if they are a narcissist, if they are dating a narcissist, if their boss is a narcissist, if their dog is a narcissist – and on and on. But far fewer seem to be asking about the polar opposite of narcissism – echoism.

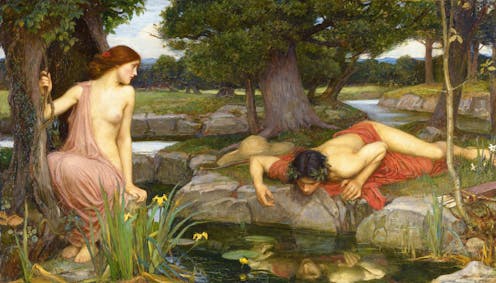

To understand this self-effacing trait, it’s worth first venturing into Greek mythology, whence the terms “narcissism” and “echoism” were derived.

Echo was a nymph with a beautiful voice – a voice she used to keep up a pleasant conversation to distract Hera, the queen of the gods, so that she wouldn’t notice her husband’s (Zeus) infidelities with Echo’s friends (other mountain nymphs).

Hera eventually understood Echo’s little game and punished her so that she no longer had control of her own tongue. Echo was only able to speak when spoken to, and she could only repeat the last words of the person who had spoken to her.

While the punishment took a heavy toll on Echo, her true suffering started when she fell in love with Narcissus, a hunter who had gained renown for his extraordinary beauty. Narcissus’s brutal rejection of Echo because of her inability to speak her own words caused her such grief that, in the end, there remained nothing of her except for her voice.

As in the myth where Echo helped other nymphs to mate with the king of the gods, echoists focus on meeting the needs of others to avoid considering their own. And they are unable to express their own desires and thoughts out of fear that this may lead to feelings of shame or loss of love. They tend to be empathetic, and they avoid or even reject attention.

Other characteristics of echoism may involve an inability to create boundaries, a tendency to take on substantial self-blame and to ask very little of others out of fear that this may burden them – or that it may be seen as an attempt to attract attention.

In the myth, Narcissus and Echo are opposites that are depicted as intertwined but separate entities. To understand echoism, you need to understand narcissism since the former is being perceived as being the opposite end of the narcissism spectrum.

Opposites attract

Echoists and narcissists may be attracted to each other. And while it may be easy to think of the narcissist as the assailer and echoist as the victim in a relationship, the truth is that both parties satisfy certain needs.

A narcissist will monopolise attention without any challenge or threat to their ego. Meanwhile, the echoist will hide in the shadows of the narcissist so their tendency to reject attention is satisfied.

Going beyond simplistic dichotomies between good and bad personalities, the moral of the myth, as well as the interpretation of recent findings on narcissism, suggest that too much or too little of anything can be catastrophic for the person and the people around them.

In the myth, both Echo and Narcissus die tragically at a very young age in despair caused by wrong choices and unmet needs. Today, both narcissistic personality disorder (the high end of the narcissism spectrum) and echoism (there is no echoism equivalent to narcissistic personality disorder) can contribute to mental health problems, isolation and loneliness.

On the other hand, a healthy – even slightly elevated – level of narcissism, mainly “grandiose narcissism” (an inflated sense of importance and a preoccupation with status and power), can contribute to positive outcomes, such as reduced mental illness and better performance under stress. This is because slightly elevated levels of grandiose narcissism have been consistently linked to increased resilience to mental disorders.

We have also shown that when under stress to perform in a cognitive test, grandiose narcissists seemed to have had the ability to ignore misleading feedback and focus on the task at hand.

But to understand how much of narcissism or echoism is needed before it becomes toxic, we need to change the way we perceive human nature. Instead of thinking about personality traits as something that is fixed (you are either an echoist or not), we should focus on understanding how our behaviour and personality changes from one day to the next depending on what is required of us within the complex societal environment that we all operate in.

Kostas Papageorgiou does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.