None of the moons in our solar system possess rings today. But a new study indicates that such rings, if created, could remain stable for a million years, even while being gravitationally pulled by other solar system objects. The findings deepen the mystery of why these satellites are now ring-free.

Rings surround many members of our planetary family. Saturn is perhaps the best-known example, swathed by eight main rings made of thousands of smaller ringlets, but the other three outer planets also possess rings, the Voyager space missions revealed. Composed of chunks of ice and rocks of varying sizes, these ring systems are maintained by small shepherding moons, whose gravitational forces tug the chunks and tweak their positions.

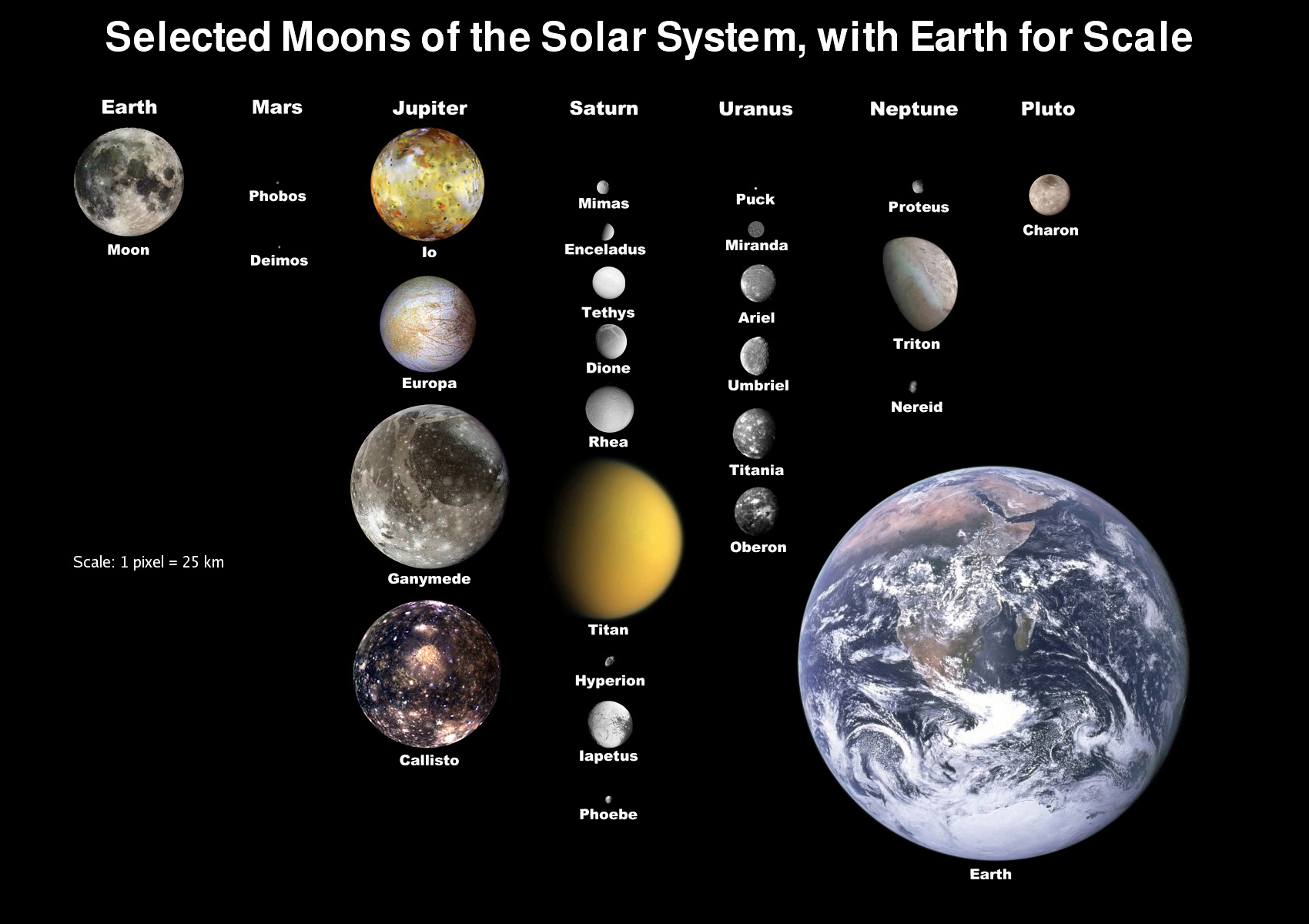

More recent studies using ground-based telescopes have revealed rings encircling several centaurs — asteroids beyond Jupiter’s orbit — and minor planets, including the egg-shaped Haumea. Even Earth and Mars may once have had rings. However, no study so far has definitively spotted rings around any of the solar system's 300-odd moons. (A 2008 study claiming that Jupiter's moon Rhea possessed a ring turned out to be a false alarm.)

This absence is all the more intriguing because the physical processes that create rings can theoretically occur on both planets and their satellites. A ring can form around an object when debris starts orbiting it, said Matthew Tiscareno, a planetary scientist at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California. This debris could be kicked up from the body's surface following an asteroid or comet collision, or may consist of icy plumes ejected by powerful cryovolcanoes. Over time, gravitational forces along the body's equatorial bulge flatten out the debris into a ring, Tiscareno told Live Science in an email. But lots of moons have suffered asteroid impacts or have cryovolcanoes — and yet, they remain ringless.

The hunt for missing moon rings

These observations prompted Mario Sucerquia, an astrophysicist at France's Grenoble Alpes University, and colleagues to investigate whether moon rings could be stable at all. A 2022 study Sucerquia co-authored found that theoretically, isolated moons could have stable rings around them. But that study didn't consider the gravitational effects of other moons and planets.

Related: What temperature is the moon?

To investigate this, in the new study published Oct. 30, 2024 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics. Sucerquia and colleagues selected five sets of spherical moons and their neighboring planets, including Earth and the moon. For each set, the team added rings to all the satellites, then simulated how the rings would behave over a million years, while being pulled gravitationally by their parent moon, other nearby moons and the planet. The researchers also calculated how chaotically the ring particles moved over a millennium, to determine the rings' stability.

The researchers expected to find that the rings were unstable, but the model showed that, barring a few moons, including Saturn's "Death Star" moon Mimas, these moon rings were stable — particularly Jupiter’s Iapetus. Even Earth's moon had a 95% chance of supporting a stable ring system in the simulations.

"[W]e did not anticipate that moons in a hostile gravitational environment, with many other moons and planets disturbing their rings, would still maintain stability," Sucerquia told Live Science in an email. But instead "these hostile environments, rather than destroying the rings, actually endowed them with great beauty by creating structures like gaps and waves, similar to those observed in Saturn's rings," he said.

Where did all the rings go?

So why don't the moons have rings today? The authors suggest that non-gravitational factors, including the sun's radiation and charged particles from the magnetic fields of the moons' parent planets, caused any previous rings to disintegrate.

Not everyone agrees with the study's findings. Tiscareno, who wasn't involved in the study, thinks in the long term, rings were likely broken by gravitational pulls from the parent moons themselves.

"Because most solar system moons rotate very slowly (keeping the same face towards their planet as they orbit, as our moon does to Earth), any ring particles must be orbiting the moon much faster than the moon spins," he said. So gravitational tugs from the parent moons, over long stretches of time, would "cause the ring particle orbits to decay until they eventually impact the surface of the moon," he said. In other words, if our moon ever had rings, they crashed to the lunar surface long ago.

.png?w=600)