Global warming caused vital Atlantic Ocean currents to collapse just before the last ice age, a new study suggests.

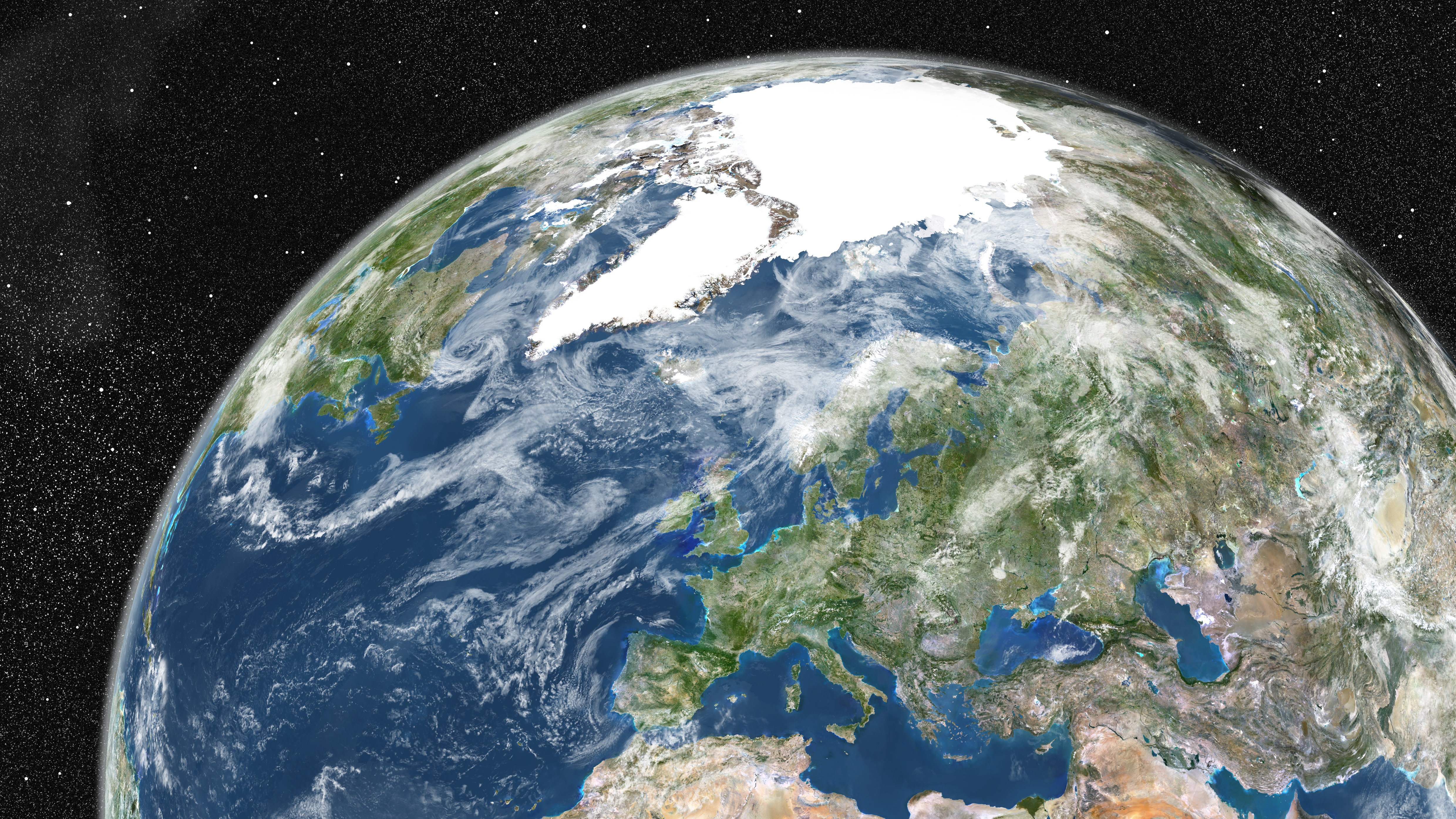

The weakening currents triggered a cascade of effects, resulting in a dramatic cooling of the Nordic Seas — the Greenland, Iceland and Norwegian seas — while the surrounding oceans grew warmer. And scientists say we could be heading toward the same thing again, as the world warms with climate change and temperatures race closer to the levels that existed before the last ice age.

"Our study is indeed alarming regarding what we might be heading to," study lead author Mohamed Ezat, an associate professor and paleoceanographer at The Arctic University of Norway, told Live Science in an email.

The Last Interglacial period (130,000 to 115,000 years ago), which occurred between the previous two ice ages, was a relatively warm stage of Earth's history characterized by higher temperatures, higher sea levels and smaller ice sheets than we see today. Climate scientists say the Last Interglacial provides an analogue for the near future if countries fail to slash greenhouse gas emissions, with temperatures reaching 1.8 to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (1 to 2 degrees Celsius) above preindustrial levels.

"The time period we investigated, the Last Interglacial, is an interesting and very timely period to study," Ezat said. "We found that about 128,000 years ago, enhanced melting of Arctic sea ice had a significant effect on the overturning circulation in the Nordic Seas."

Nordic Sea currents play a critical part in a wider system of Atlantic Ocean currents called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which includes the Gulf Stream. The AMOC is essential for warming the Northern Hemisphere and functions like a giant conveyor belt, with warm waters from the Southern Hemisphere riding northward on the ocean surface and then cooling and plunging to the bottom in the North Atlantic to travel back south.

Melting ice in the Arctic can significantly impact the AMOC, because fresh water pouring into the North Atlantic dilutes surface waters, preventing them from sinking to the bottom to form deep currents. Research shows the AMOC is already slowing down as a result of global warming, and scientists say the system could grind to a halt in the coming decades.

Earlier this month, 44 leading climate scientists rang the alarm bell on the AMOC in an open letter addressed to the Nordic Council of Ministers, an intergovernmental forum that promotes cooperation between the Nordic countries. The letter outlined the risks linked to an AMOC collapse, including major cooling in the Northern Hemisphere and catastrophic shifts in tropical monsoon patterns.

Climate models suggest the AMOC could collapse before 2100, but there are huge uncertainties in predicting the timescales. "Looking at the distant past of the Earth's climate history in particular when it was warmer than today can reduce such uncertainties," Ezat said.

For the new study, Ezat and his colleagues analyzed new and existing data from sediment cores from the Norwegian Sea. They compared these data to similar information from North Atlantic sediments to reconstruct the sea ice distribution, sea surface temperature, salinity, deep ocean convection and sources of meltwater during the Last Interglacial.

The results, published Oct. 27 in the journal Nature Communications, suggest Arctic meltwater blocked the formation of deep-ocean currents in the Norwegian Sea during the Last Interglacial. This considerably slowed the southward flow of the AMOC, in turn slowing the engine that brings heat to the Northern Hemisphere.

"In brief, we found cooling in the Nordic Seas that we were able to link to a warming global climate and enhanced melting of sea ice," Ezat said.

The study highlights what could happen to the AMOC in the near future, Ezat said. Satellite observations show a drastic decline in Arctic sea ice over the past four decades, and scientists say ice-free summers will likely take hold by 2050. These will have major consequences for the AMOC.

"It sends out another reminder that our planet's climate is a delicate balance, and that climate action is an emergency," Ezat said. "We know that severe weakening of the AMOC isn't unlikely, and if it happens it will have serious implications [for] the high latitude regions and beyond."