Dina Ndelini had been working on vineyards around Cape Town for more than 40 years when she was suddenly struck with breathlessness. A trip to the hospital quickly spiralled into a series of events which saw her lose her health, her job and, along with it, her home.

According to her doctor, the most likely culprit was exposure to a chemical concoction known as Dormex. Commonly used as a plant growth regulator in South Africa its active ingredient, cyanamide, has been described as highly dangerous by the EU Chemicals Agency (ECHA) and banned in the EU since 2009.

Despite this, Dormex is just one on a long list of highly hazardous chemicals which continue to be produced on European soil and sold to third countries. Food made abroad using these chemicals is then imported to be sold on Europe’s supermarket shelves.

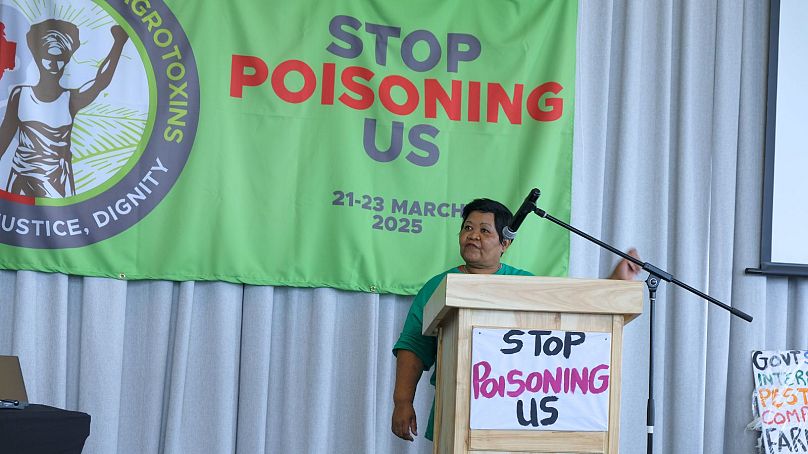

Dina’s was one of the many stories shared by farm workers as well as legal and health professionals at a recent People’s Tribunal on Agrotoxins, which took place in the heart of the world-renowned wine region of Stellenbosch on 21-23 March.

While not a formal court, these community-led tribunals provide a space for those impacted to share their testimonies in front of expert judges to consider allegations of international law violations, including environmental and human rights.

South African farm workers urge Europe to stop sending ‘poisons’

Asked for her message to Europe, Dina was clear. “We say as farm workers, enough is enough - we don’t want anymore these pesticides from Europe,” she says, urging the bloc to “stop sending us its poisons”.

The sentiment was echoed many times over the course of the two-day tribunal, with farm workers taking the stand to share their stories of the impact of pesticide exposure on their lives, from lung damage, to ovarian cancer and impaired vision.

“If it’s not good enough for Europeans, why do they think it’s good enough for us?” says another farm worker, who wished to remain anonymous, adding that European consumers should know “the human reality behind the wine they are drinking”.

According to the African Centre for Biodiversity, 192 highly hazardous pesticides are still legally in use in South Africa, 57 of which are banned for use in the EU. Some are neurotoxic or cancer-causing, while others are considered acutely toxic for the environment.

Those on the frontline of exposure are the farm workers and their families living in the vicinity of spraying, who fall on the lowest rung of the country’s complex wealth and power inequalities, rooted in its apartheid past.

Commonly overworked, underpaid, and poorly protected on precarious contracts, farm workers have very little say in the running of these farms, managed by wealthy landowner boers (‘farmers’).

Those most at risk are women, who are both biologically more susceptible to pesticide exposure and more vulnerable in South African societies, according to South Africa’s Women on Farms project (WFP), an NGO working to protect women farm workers in the Western and Northern Cape.

Throughout the tribunal, workers repeatedly said personal protective equipment was not provided to them, with many testifying that women commonly bring scarves to cover their faces while they work. Others reported having no access to running water or toilets on the vineyards.

Banned pesticide exports a ‘blatant double standard’

Attempts to align trade standards are in the spotlight in Brussels, with the publication of a new EU policy roadmap for agriculture setting out plans to restrict food imports from third countries with residues of pesticides banned in Europe.

This is not the first time that the EU has considered such a move, with murmurings that the Commission may stop the export of banned pesticides circulating for years.

But the plans face staunch opposition from agroindustry groups, including pesticide lobby CropLife, which has long argued that these pesticides are necessary in certain circumstances.

“The production realities of South African agriculture are vastly different, so it is difficult to compare to other countries and regions,” CropLife South Africa said in a statement following the tribunal. It maintains that different crops, pests and climatic conditions require “different solutions and pesticides at different times”.

This argument does not hold weight for UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, Dr Marcos Orellana. “The human body is the same everywhere - what differs is the lack of capacity of the government institutions to deal with the risks imposed on people in vulnerable situations,” he says, calling it a “blatant double standard”.

International protections a ‘tick box’ exercise

South Africa does have legal systems governing the use of such chemicals and is working towards a phase-out of highly hazardous pesticides in the near future, but tribunal participants argued that enforcement is often lacking. Meanwhile, farm workers are often unaware of or reluctant to advocate for their rights.

For the UN’s Orellana, the argument that governments are sovereign to make their own decisions “underscores [the] lack of capacities in many, if not most, developing countries involved in international trade of pesticides” and excludes the issue of “corruption and corporate capture of the government institutions that make these decisions”.

More widely, an international treaty called the Rotterdam Convention is designed to encourage informed decision-making by countries that trade in hazardous chemicals.

But for Dr Andrea Rother, head of the environmental health division at the University of Cape Town, the convention is too cumbersome to be effective. “By the time a pesticide gets listed, they are often obsolete,” she says, adding that the convention is “more of a rubber stamping, ‘tickbox’ exercise” than a true safeguard mechanism.

Pointing out that no African country manufactures its own pesticide ingredients, Rother maintains a ban on the EU side would be a “huge help” for South Africa.

“There are alternatives to these pesticides,” she says, arguing that such an export ban could be a “catalyst” towards more sustainable agricultural systems.

For WFP’s campaigns coordinator, Kara MacKay, each day that the EU continues the production and export of these EU-banned chemicals to South Africa is another that it is “complicit in the daily pesticide poisoning of farm workers and dwellers”.

“We must end this toxic trade - to argue any differently reveals a racist and colonial thinking that is unjustified,” she says.

In the meantime, the expert judges adjudicating the People’s Tribunal will evaluate the evidence presented by Dina and the rest of the farm workers, before offering their verdict and legal advice in a few months time.