In 1770, Barnard Gratz of Philadelphia wrote to a friend complaining about a recent speech by King George III. Gratz, an American patriot, wrote that the speech “was such narishkeit” that it was “not worth the postage.”

Narishkeit is Yiddish for “nonsense.”

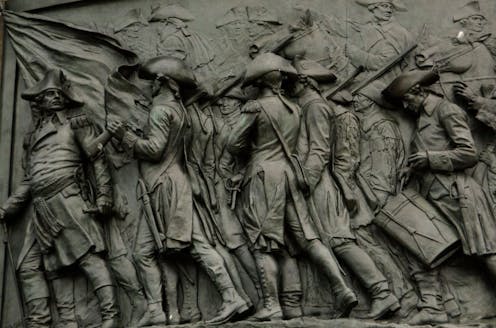

Gratz was one of hundreds of Jews who joined the American Revolution as soldiers and leaders: Gershom Seixas led his synagogue out of New York when the British invaded and led what was probably the first Jewish prayer group in Connecticut. Solomon Bush earned the rank of lieutenant colonel in the American army; at the time, no Jew in Europe could serve as a military officer. At the battle of Beaufort, one of the patriot militias was nicknamed “the Jew Company” because 28 of its 40 members were Jewish.

Yet belief persists that the American Revolution was somehow a Christian event – and that the country it created is therefore a Christian nation. This is a position usually defended with vague statements about what the Founding Fathers wanted. The general idea is that back in the day, everyone was Christian and so, of course, the founding was Christian. Yet neither the Declaration of Independence nor the Constitution refer to a “Christian nation” or a church. They don’t even mention Jesus Christ.

But as a historian, I didn’t want to get caught up in these kinds of arguments. I wanted to know something about the people who actually did the fighting in the war.

What I discovered is that when it came to fighting Britain, there were plenty of Jewish patriots signing up. America’s revolutionaries were not a uniform bunch of Christian white guys. The Revolution was a religiously diverse place, from Jews and religious skeptics to Catholics and Christian dissenters. And that matters for how the U.S. defines itself and its freedom today.

Jews join the cause

When the war started in 1775, the roughly 2,500 Jews in the Colonies did not have religious freedom. British law allowed them to practice, but they were classified as “residents” rather than subjects. They could live there, but they had no say in the laws under which they lived. For the most part, only property-owning Protestant men could elect or be elected to their legislature. Jews were simply not considered people the way Protestant Christians were.

So when the break with Britain arrived, American Jews flocked to the standard of liberty. Here at last was a chance to become citizens.

Under British rule, anyone who exercised political authority had to take an oath affirming their Christian faith. The pro-independence groups and militias that sprung up amid the war had no such rules. Mordecai Sheftall, who lived in Georgia, was one of the few people there who had pledged to resist the Coercive Acts: Britain’s efforts to blockade Boston and place Massachusetts under military rule after the Boston Tea Party. When the war broke out, Sheftall became chairman of Georgia’s de facto government, in defiance of British rule.

Jewish residents took up arms for independence, too. A South Carolina writer praised American Jews fighting for liberty, saying they were “as staunch as any other citizens of this state.” One signer of the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Rush, believed “the Jews in all the states” were patriots. So did royalist Gov. James Wright of Georgia. When the British seized Savannah, Wright banned Jews from the province, calling them “violent rebels and persecutors of the King’s loyal subjects.”

When the war ended, Philadelphia hosted a parade and all the clergy of the city were invited, including Jewish leaders. There was even a kosher table set out for them after the celebration.

‘Second-status’ Christians

Nor were Jews the only marginalized group to join the cause. Roman Catholics also signed up. Like Jews, Catholics were barred under the British from serving in public office. As a Catholic, Charles Carroll could not have served in the royal government of Maryland, but he went on to sign both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

The Baptists of Virginia were also held in second-class status. The Colony’s state church did not recognize the Baptists, and they had to pay fines for preaching and even for holding Baptist weddings without state sanction. Virginia Baptists promised their support to the Revolution only if Virginia would offer them religious freedom. The Virginia Legislature complained but suspended its state church to build whatever support it could find. Virginia Baptists joined the fight in droves.

Baptists, Catholics and Jews were not put off by any of the Revolution’s radical deists: a mostly unorganized group of religious thinkers who believed in God and reason, but not revelation or miracles. Their ranks included military officer Ethan Allen of Vermont, who later wrote a book denying the divinity of the Bible. The Revolution did not ask its members how they prayed.

The urge for liberty spread beyond questions of religious differences. Although George Washington did not originally want to enlist Black men in the army, he realized the Revolution was doomed without them, and thousands of Black Americans joined the cause in the hope that liberty would mean the end of slavery. Women such as Deborah Sampson wore men’s clothing to take up arms against the British. The revolutionaries even had a Muslim ally in the form of Hyder Ali and his armies. The Muslim ruler of the kingdom of Mysore, in southern India, Ali fought with France against Britain in the 1780s, and American revolutionaries named a ship after him.

Here from the start

In recent years, violence and anger have risen against minority groups, including Jewish and Muslim Americans. Part of the false rhetoric about these groups has been that they are “new”: that they appeared after America was created and are not really part of the American experiment. In fact, they were here from the beginning. They also fought for the Revolution. Their patriotism is as old as anyone else’s.

Not only were the people who founded the nation not all Christian, but after independence was secured, religious freedom actually increased.

States with synagogues all lost the Christian requirement for public office by 1792. Virginia created full religious freedom in 1786. And Washington wrote, “It is our boast, that a man’s religious tenets will not forfeit the protection of the laws, nor deprive him of the right of attaining and holding the highest offices that are known in the United States.”

Calls for a Christian nation are historically false. They are not a reversion to something old; they are something new. Religious diversity in America, and the freedom of different religions to be full Americans? That’s old. As old as the Revolution.

Adam Jortner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.