Earlier this month, China declared new “baselines” around Scarborough Reef, a large coral atoll topped by a handful of rocks barely above sea level in the South China Sea.

By doing so, China reaffirmed its sovereignty claim over what has become a global flashpoint in the disputed waters.

This was a pre-calculated response to the Philippines’ enactment of new maritime laws two days earlier that aimed to safeguard its own claims over the reef and other contested parts of the sea.

This legal tit-for-tat is a continuation of the ongoing sovereignty and maritime dispute between China and the Philippines (and others) in a vital ocean area through which one-third of global trade travels.

The Philippines rejected China’s declaration as a violation of its “long-established sovereignty over the shoal”. Defence Secretary Gilberto Teodoro said:

What we see is an increasing demand by Beijing for us to concede our sovereign rights in the area.

As the tensions continue to worsen over these claims, there is an ever-increasing risk of an at-sea conflict between the two countries.

What is the Scarborough Reef?

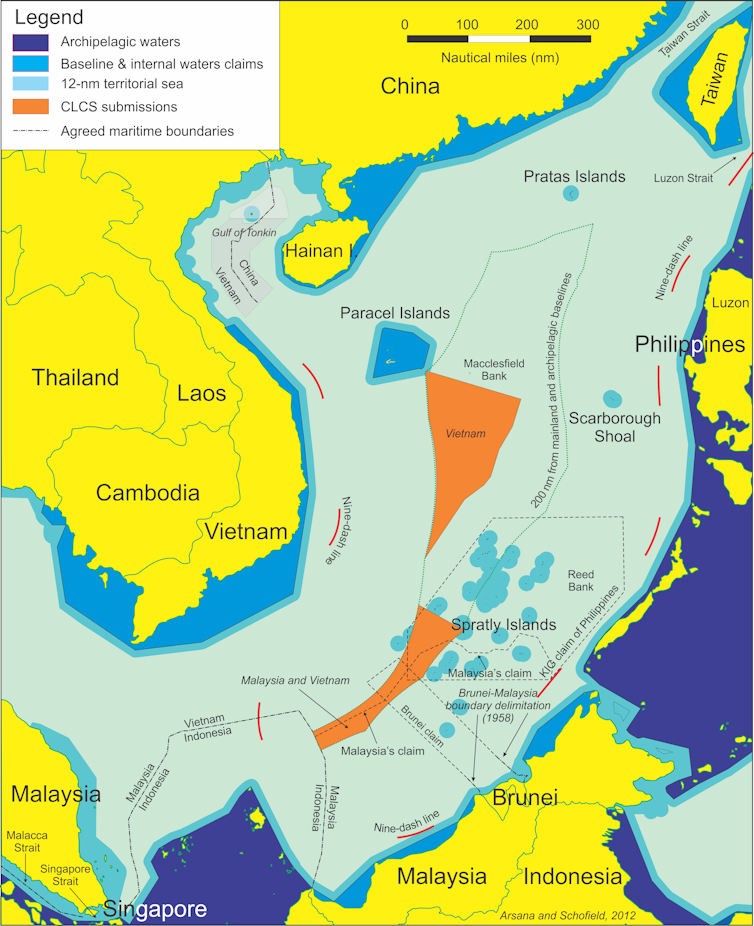

Scarborough Reef is called Huangyan Dao in Chinese and Bajo de Masinloc by the Philippines. It is located in the northeast of the South China Sea, about 116 nautical miles (215km) west of the Philippine island of Luzon and 448 nautical miles (830km) south of the Chinese mainland.

At high tide it is reduced to a few tiny islets, the tallest of which is just 3 metres above the water. However, at low tide, it is the largest coral atoll in the South China Sea.

China asserts sovereignty over all of the waters, islands, rocks and other features in the South China Sea, as well as unspecified “historic rights” within its claimed nine-dash line. This includes Scarborough Reef.

In recent years, the reef has been the scene of repeated clashes between China and the Philippines. Since 2012, China has blocked Filipino fishing vessels from accessing the valuable lagoon here. This prompted the Philippines to take China to international arbitration under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 2013.

Three years later, an arbitration tribunal ruled that China has no historic rights to maritime areas where this would conflict with UNCLOS. The tribunal also concluded China had “unlawfully prevented Filipino fishermen from engaging in traditional fishing at Scarborough Shoal.”

China refused to participate in the arbitration case and has strongly rejected its ruling as being “null and void” and having “no binding force”.

What did China do this month?

China declared the exact location of the base points of its territorial claim around Scarborough Reef with geographical coordinates (longitude and latitude), joined up by straight lines.

The declaration of so-called “baselines” is standard practice for countries that want to claim maritime zones along their coasts. Baselines provide the starting point for measuring these zones.

A country’s “territorial sea” is measured from this baseline outward to as far as 12 nautical miles (22km). Under the UNCLOS treaty, a country then has full sovereignty rights over this zone, covering the seabed, water, airspace and any resources located there.

Countries want their baselines to be as far out to sea as possible so they can maximise the ocean areas over which they can reap economic benefits and enforce their own laws.

China is no exception. Along with other countries (especially in Asia), it draws the most generous baselines of all – straight baselines. These can connect distant headlands or other coastal outcrops with a simple straight line, or even enclose nearshore islands.

China is especially fond of straight baselines. In 1996, it drew them along most of its mainland coast and around the Paracel Islands, a disputed archipelago in the South China Sea. China defined additional straight baselines this March in the Gulf of Tonkin up to its land border with Vietnam.

China says these actions comply with UNCLOS. However, its use of straight baselines around Scarborough Reef conflicts with international law. This is because UNCLOS provides a specific rule for baselines around reefs, which China did not follow.

Based on our review of satellite imagery, however, China has only advanced the outer limit of its territorial sea by a few hundred metres in two directions. This is because its straight baselines largely hug the edge of the reef.

These new baselines around Scarborough Reef are therefore fairly conservative and enclose a dramatically smaller area than the US had feared.

China’s declaration signals that it may have abandoned its much larger “offshore archipelago” claim to what it calls the Zhongsha Islands.

China has long asserted that Scarborough Reef is part of this larger island group, which includes the Macclesfield Bank, a totally underwater feature 180 nautical miles (333 km) to the west. This led to concern that Beijing might draw a baseline around this entire island group, claiming all the waters within exclusively for its use.

The South China Sea arbitration tribunal ruled that international law prohibits such claims. There will be a collective sigh of relief among many countries that China decided to make a much smaller claim over Scarborough Reef.

Significance and future steps?

However, China’s clarification of its baselines around the reef signals it may be more assertive in its law enforcement here.

The China Coast Guard has said it will step up patrols in the South China Sea to “firmly uphold order, protect the local ecosystem and biological resources and safeguard national territorial sovereignty and maritime rights”.

Given the long history of clashes related to fishing access around Scarborough Reef, this sets the scene for more confrontation.

And what about the biggest prize of all in the South China Sea – the Spratly Islands?

We can now expect China will continue its long straight baselines march to this island group to the south. The Spratlys are an archipelago of more than 150 small islands, reefs and atolls spread out over around 240,000 square kilometres of lucrative fishing grounds. They are claimed by China, as well as the Philippines and several other countries.

These countries can be expected to protest any attempted encirclement of the Spratly Islands by new Chinese baselines.

Clive Schofield served as an independent expert witness appointed by the Philippines in the South China Sea arbitration case.

Warwick Gullett and Yucong Wang do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.