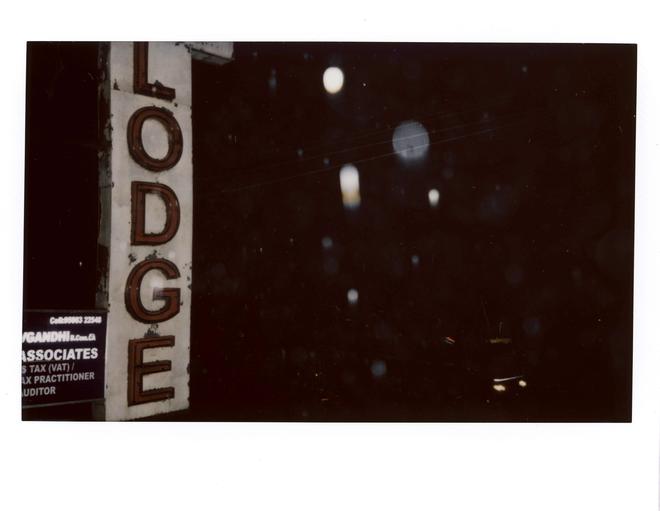

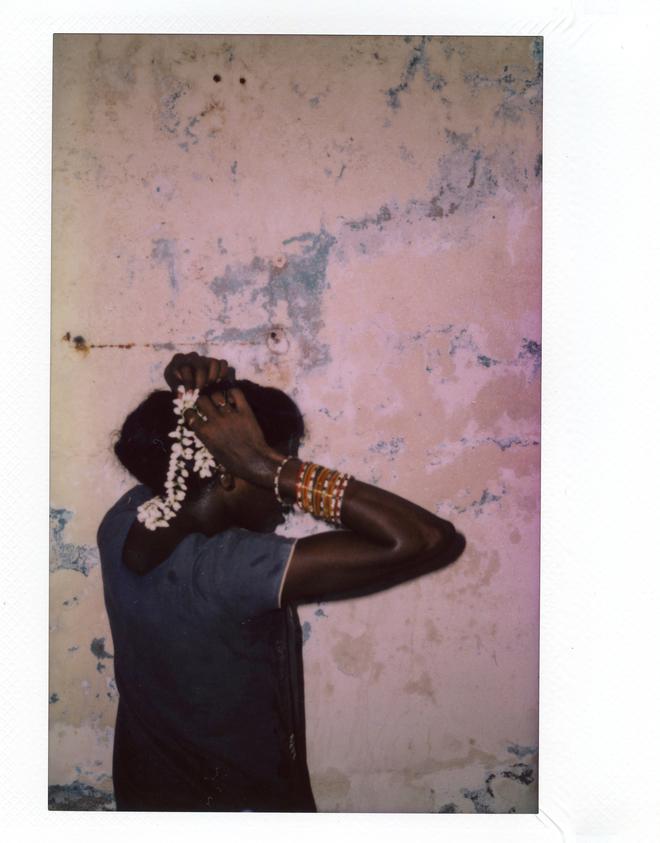

Small, muggy rooms with peeling paint; mouldy sheets and pillow covers with lipstick stains: photographer Jaisingh Nageswaran’s photo series The Lodge is a study of the spaces people live in during the Koothandavar festival at Koovagam in Villupuram. The 18-day festival is an annual affair, and draws thousands of transpeople from across India as well as other parts of the world.

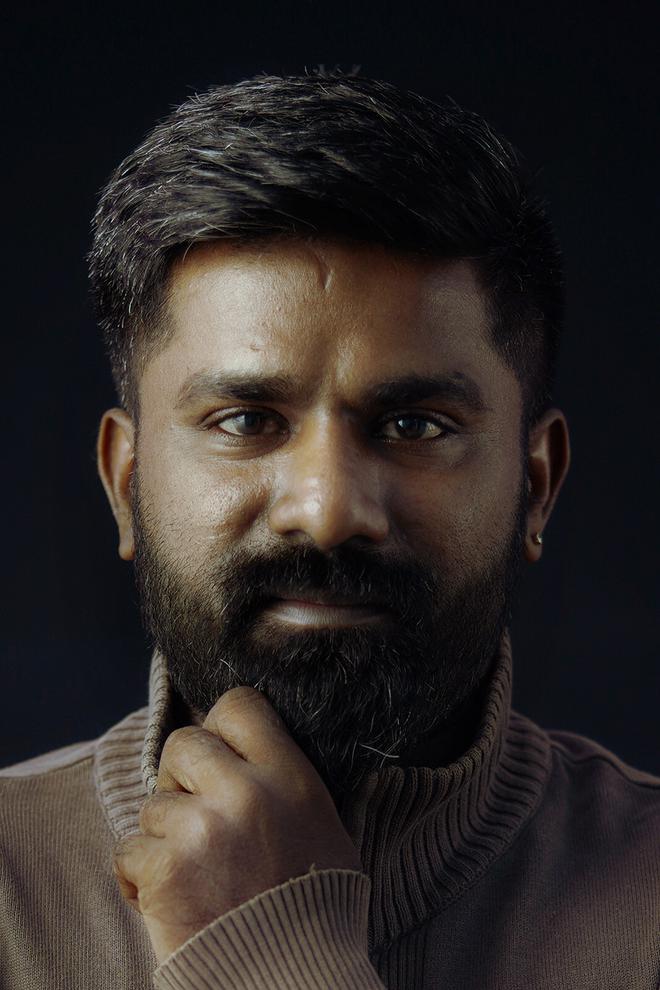

“For us, a stay at a hotel implies a relaxed time in a clean, comfortable room,” says the 45-year-old lensman. He says that he has tried to get a glimpse into several different lives by examining the region’s lodges. Thirteen years of documenting the Koothandavar festival has left him with many questions, memories, friendships, and of course, photographs.

The Lodge is now on display at the Kyotographie Photo Festival at Kyoto, Japan, where Jaisingh was selected as the Grand Prix winner for 2023. This is the first time an Indian has won at the prestigious event.

Jaisingh, back home at Vadipatti near Madurai after a trip to Kyoto, recalls his first interactions with people from the transgender community. “My work is a reflection of my accumulated life experiences,” he says. He remembers Subbu, a friendly transwoman who was his neighbour in his younger days. She had a big bindi on her forehead and wore her long hair in a knot.

Years later, when he was on a train to Mumbai to work as an assistant cameraperson for cinematographer Ravi K Chandran, he encountered them again. “People were very discriminatory; they fled the scene or hid when they approached them. I too turned my gaze away,” he says. Jaisingh was disturbed by his reaction and that of his fellow passengers. When he learned of the popular festival at Koovagam, he was instantly drawn to it.

This was in 2006, and Jaisingh went with no idea of what to expect. He initially didn’t take his camera along, and admits to fearing that his belongings would be extorted by them, as is the common prejudice. After four years, he realised how wrong he was.

Koovagam has been extensively covered by Indian photographers as well as those from Western countries. Most of these images are filled with colour and action from the rituals that surround the Koothandavar temple. But Jaisingh’s camera captures the raw life in the narrow by-lanes of the village: its seedy underbelly that is filled with cramped lodges, some of which are used for sex work.

Behind the label

“On one such visit, a group of four to five transgender people asked me why I hung around the lodges all the time,” he recalls. They invited him inside their room, and eventually, into their world. Jaisingh gradually got to see the people behind the label of ‘sex workers’. “No one asked them what their favourite book was, what they liked to eat, what their desires were,” he says.

Then, he started to take photos. “I also took shots with a Fiji Instax instant camera so that I could show them the output right there,” he says. Jaisingh recalls meeting several unconventional people at the festival. “There was a cross-dresser who liked to wear stockings since he grew up watching James Bond films. His wife knew about this, but he told his children he was going on a pilgrimage every time he came there.”

Thanks to his obsession with the festival, Jaisingh says that his friends and peers started questioning his sexuality. “They repeatedly asked me if I was gay, despite me telling them that I was straight,” he says.

Jaisingh is now working on a series on his family’s story, that will be displayed next year at Kyoto. He explains: “I want to give an insider account of a Dalit family, talk about not just its struggles, but happiness as well.”