Statements have been circulating online, including leading news platforms, that battery electric cars will greatly increase the average mass of the on-road fleet. This claim is used as an argument against these cars.

Even the Australian motoring organisation NRMA has posed the question: “EVs are heavy. Are they safe on our roads and carparks?” (It does say the answer is yes.)

The stated reason for such concerns is generally that electric car batteries are heavy and increase overall vehicle mass. A heavier vehicle needs more energy to drive it and so will typically increase emissions. A greater mass also reduces traffic safety and could have damaging impacts on parking spaces and roads.

A critical review released yesterday took a closer look at these claims to see if they hold true in Australia. It finds these claims don’t stack up in a country where sales of fossil-fuelled (petrol, diesel, LPG) vehicles skew towards large and heavy utes and SUVs.

When adjusted for actual top 10 vehicles sold and using realistic mass values, the average mass of battery electric and fossil-fuelled cars differs by just 68 kilograms. That difference is not significant, especially because electric cars are much more energy-efficient.

Oversimplifying a complex topic

The claims being made often oversimplify a complex reality. They tell only part of the story, which can be misleading.

For instance, internal combustion engine cars have consistently increased in mass over time. Known as car obesity, this fact is often unfairly ignored in comparisons.

Similarly, these statements pretend to know how complex consumer behaviour will respond to future availability of battery electric cars and their fast-changing and improving features. Often, the results of overseas studies cannot be directly applied to different Australian conditions.

4 points of contention

Our report identifies and unpacks four main points of contention.

First, there are different ways to define and compare the mass of battery electric and combustion engine cars. In practice, the choice is rather arbitrary. Depending on the method, the comparison may be neither adequate nor accurate.

Often the comparison is made between similar or similarly sized battery electric and combustion engine cars. Or electric cars can be compared only to an equivalent non-electric version of models such as the VW Golf. Another variation is to simply compare the average mass of a large range of cars currently on sale, without considering the impact of sales volumes.

Second, a common argument is that batteries are heavy, so electric cars are heavier than fossil-fuelled cars. But this is simplistic – it’s not only the battery that matters.

Offsetting the extra battery mass, other parts of the electric car such as their motors are smaller and lighter. They can cut its mass by up to 50%.

And actual extra battery mass itself depends on a range of factors. Battery chemistry, battery size and energy storage capacity (which determines how often a car needs recharging) all affect the mass. Indeed, battery mass varies between 100 and 900 kilograms for cars.

Third, car obesity has greatly and consistently increased fossil-fuelled car mass. Unless we include this rise in car obesity, the comparison with battery electric cars tells only half the story.

Finally, it is challenging to accurately predict the mass impacts of electric cars. A common assumption is that future vehicle buyers’ behaviour does not change when switching to battery electric cars. This assumption seems unlikely and again oversimplifies the comparison.

For instance, market availability, marketing focus, purchase price and performance characteristics will largely guide buyers’ decisions. These considerations are all highly dynamic. They are changing significantly and fast.

So how do they compare in Australia?

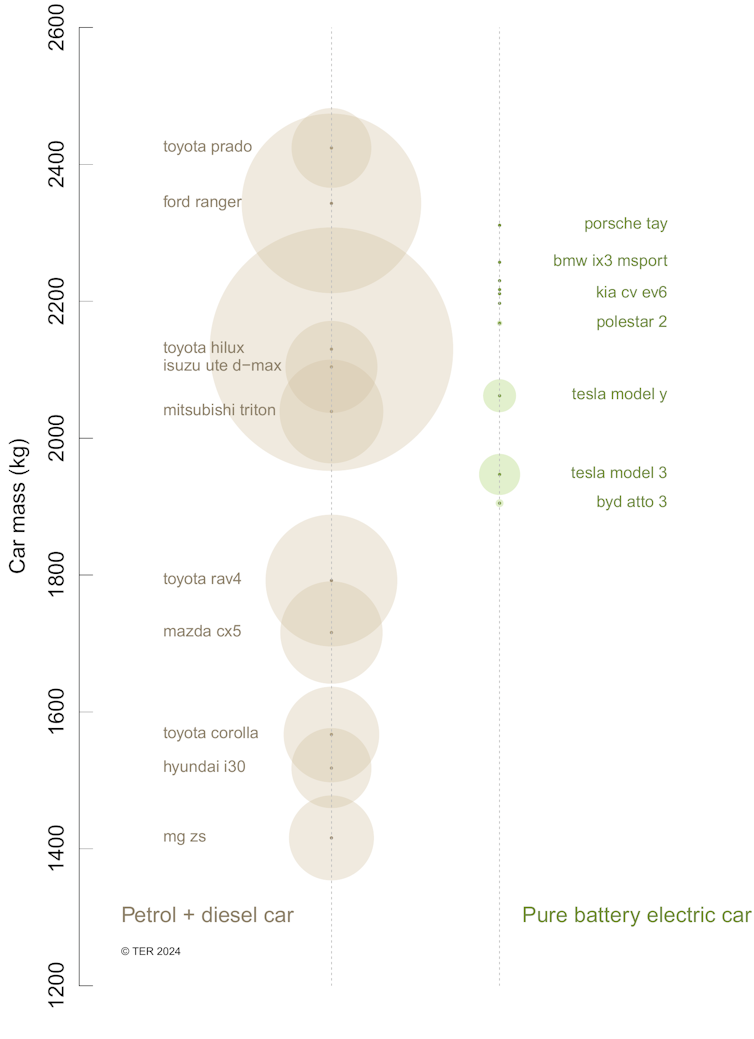

A proper comparison needs, at least, to include realistic vehicle mass and sales data. Our study compares the differences in vehicle mass between the top ten best-selling cars for both battery electric and fossil-fuelled vehicles in Australia in 2022, as shown below.

Currently sold top 10 models of battery electric cars cluster more at the heavy end, but the most popular cars are relatively light. The top 10 models of fossil-fuelled cars have a larger spread in mass. Yet, when it comes to sales, most are relatively heavy SUVs or utes.

When ranked by popularity and compared, battery electric cars are not always heavier. They can be almost 300kg (12%) lighter to almost 800kg (55%) heavier than the corresponding fossil-fuelled car. Importantly, the overall difference in the average mass of the two categories when adjusted for sales is just 68kg (about 3% of total vehicle mass).

This small difference is insignificant in terms of energy and emission impacts. A more important factor here is the superior energy efficiency of battery electric vehicles.

How will they compare in future?

Clearly, future sales profiles may differ from current sales profiles. The current profile may be largely defined by a certain type of customer (such as a high-income early adopter). They might not be typical of mainstream consumers in coming years.

Buyers’ future behaviour is uncertain and hard to predict. It would depend on the effectiveness of (new) policy measures such as Australia’s New Vehicle Efficiency Standard, the actual vehicles offered for sale, marketing efforts by car suppliers and possibly also cultural changes.

Any shifts in buyer behaviour could greatly influence the car fleet’s average mass. They could continue the current trend towards larger and heavier vehicles, or shift to smaller and lighter vehicles.

But this is the point: the impacts of electrification of passenger vehicles on average mass are highly uncertain. Statements on the matter are often speculative and can be unfairly biased by the methods used.

In markets where heavy petrol and diesel vehicles dominate car sales, such as Australia and New Zealand, current evidence suggests increased electric car sales are unlikely to greatly increase average vehicle mass. In fact, average mass could actually go down as cheaper and lighter electric cars go on sale here.

Vehicle mass remains important

Importantly, the report is not downplaying the importance of vehicle mass for transport emission abatement.

In previous research it was estimated that only a passenger vehicle fleet dominated by small and light battery electric vehicles may get Australia close to achieving the net-zero emissions target in 2050.

To meet the target, it is thus important to reverse the trend of increasing car obesity, for all cars. But vehicle mass should not be used as an argument against electrification.

Robin Smit is the founding Research Director at the Transport Energy/Emission Research (TER) consultancy.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.