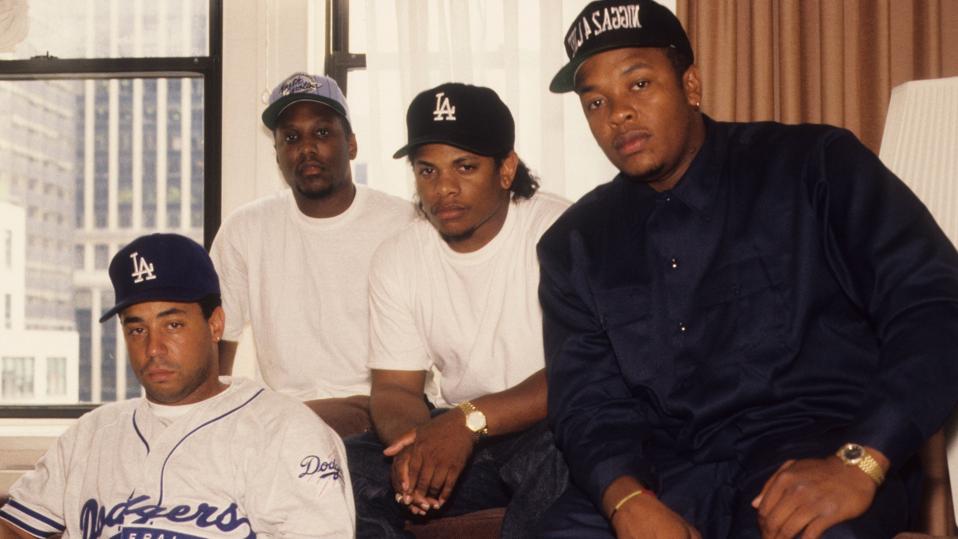

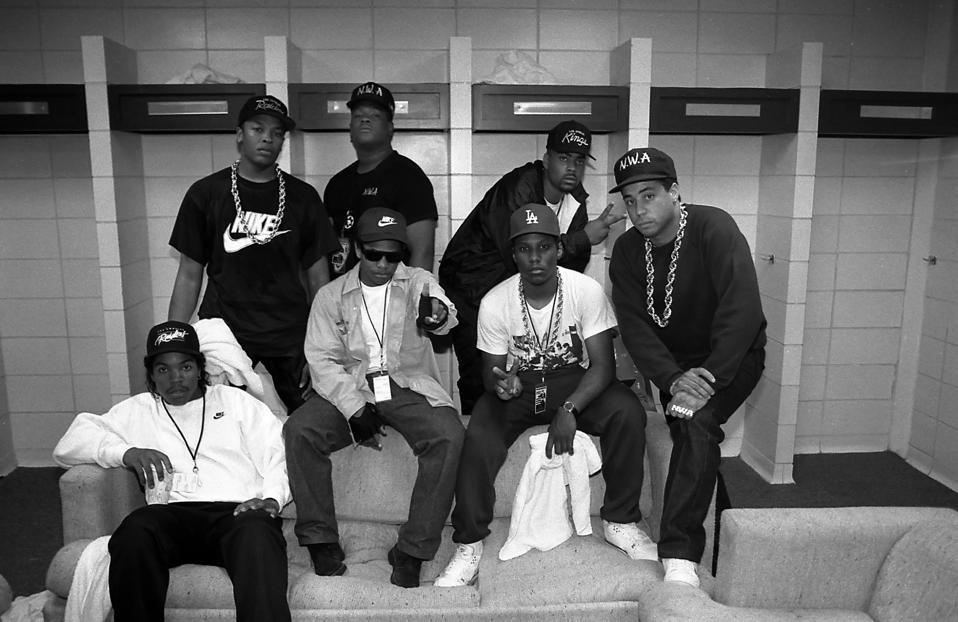

Before NWA changed the music world with its 1988 record Straight Outta Compton, a young DJ Yella made quick cash performing in the most unexpected places, from high school dances to Chuck E. Cheese arcades. If the thought of seeing a member of “The World’s Most Dangerous Group” spinning records next to a pizza-pushing animatronic rat entices you, many tales from the producer’s memoir will leave an impression.

In Antoine “DJ Yella” Carraby’s autobiography, Straight Outta Compton: My Untold Story, out now, the NWA scratchmaster details a trajectory synonymous with the most quintessential and—albeit cliché—truthful rags-to-riches overnight success stories.

Carraby’s path is filled with triumph, tragedy and loss. But the book is also filled with moments of humor and unexpected stories from a group that has been mystified and reduced to a symbol of violence and anger at the emergence of mainstream gangster rap music.

At its darkest, Carraby’s memoir describes the saddest moments of his life as a boy—losing his brother in an accidental shooting—and as a man—losing his friend and hip-hop partner, Eric “Eazy-E” Wright, to the AIDS epidemic. The DJ recounts his choices with incredible honesty: painfully detailing his history of reckless financial decisions, quitting music to direct pornography and ultimately experiencing more than three years of homelessness. Somehow, at his lowest, he didn’t even consider returning to music.

“Once I hit rock bottom ... I was in a tunnel with no light,” 54-year-old Carraby explains. “I didn't have no thoughts of, ‘Oh, maybe I can do a record.’ It was just, it is what it is, you know?”

He continues: “I put myself there. I wasn't mad at God. I can't blame nobody. But, I had to go through all that to come out the other side. Now I can appreciate even one spoon in the house. Wisdom is the key to everything. People don't understand this. You can have a bunch of money, but it don't mean anything if you don't do nothing right with it.”

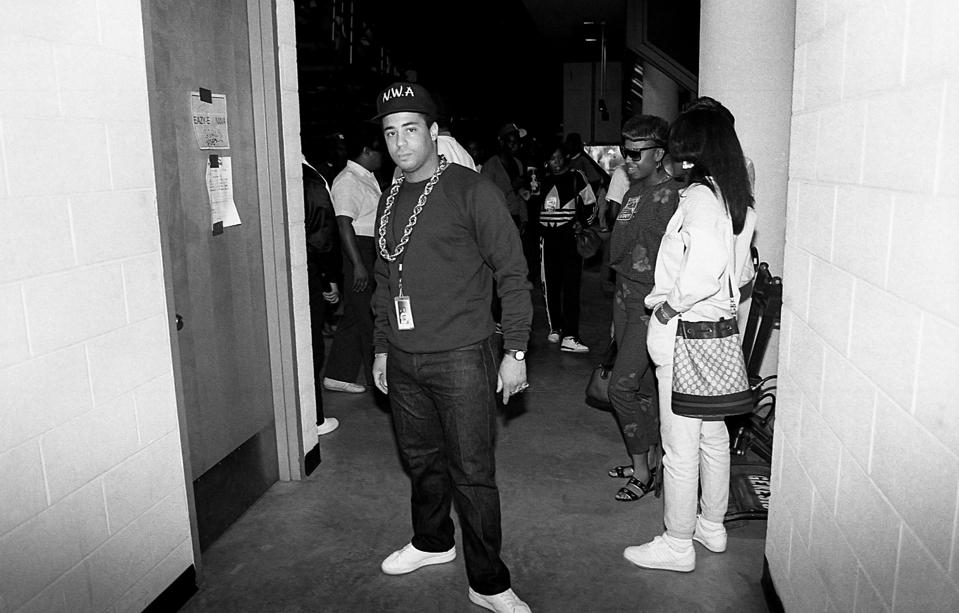

Eventually, Carraby turned to religion, his community and old friends to get back on his feet. In the years leading up to the global shutdown from COVID-19, Yella was back to touring the world as a DJ, performing with Eazy-E’s son and even playing reunion shows with original members of NWA at festivals like Coachella. He was portrayed in the Hollywood blockbuster biopic, aptly named Straight Outta Compton, inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and honored at the MTV Movie Awards.

Inspired and stabilized, Carraby compiled his life story. And while the aforementioned gets incredibly heavy, the memoir also has moments of extreme levity. For all the stories that are uplifting or defeating, many are equally as silly and absurd.

Take for example, a recollection of NWA members having a philosophical as to whether or not they’d sell their souls to the devil.

Or, a hysterically nerve-wracking anecdote where Carraby was hospitalized for surgery and Dr. Dre thought it was funny to pretend to tug at his catheter.

Perhaps the most ridiculous of memories is when Carraby was trying to focus on directing one of his adult movies and Eazy-E was in the background distracting him by loudly crunching down a bag of potato chips.

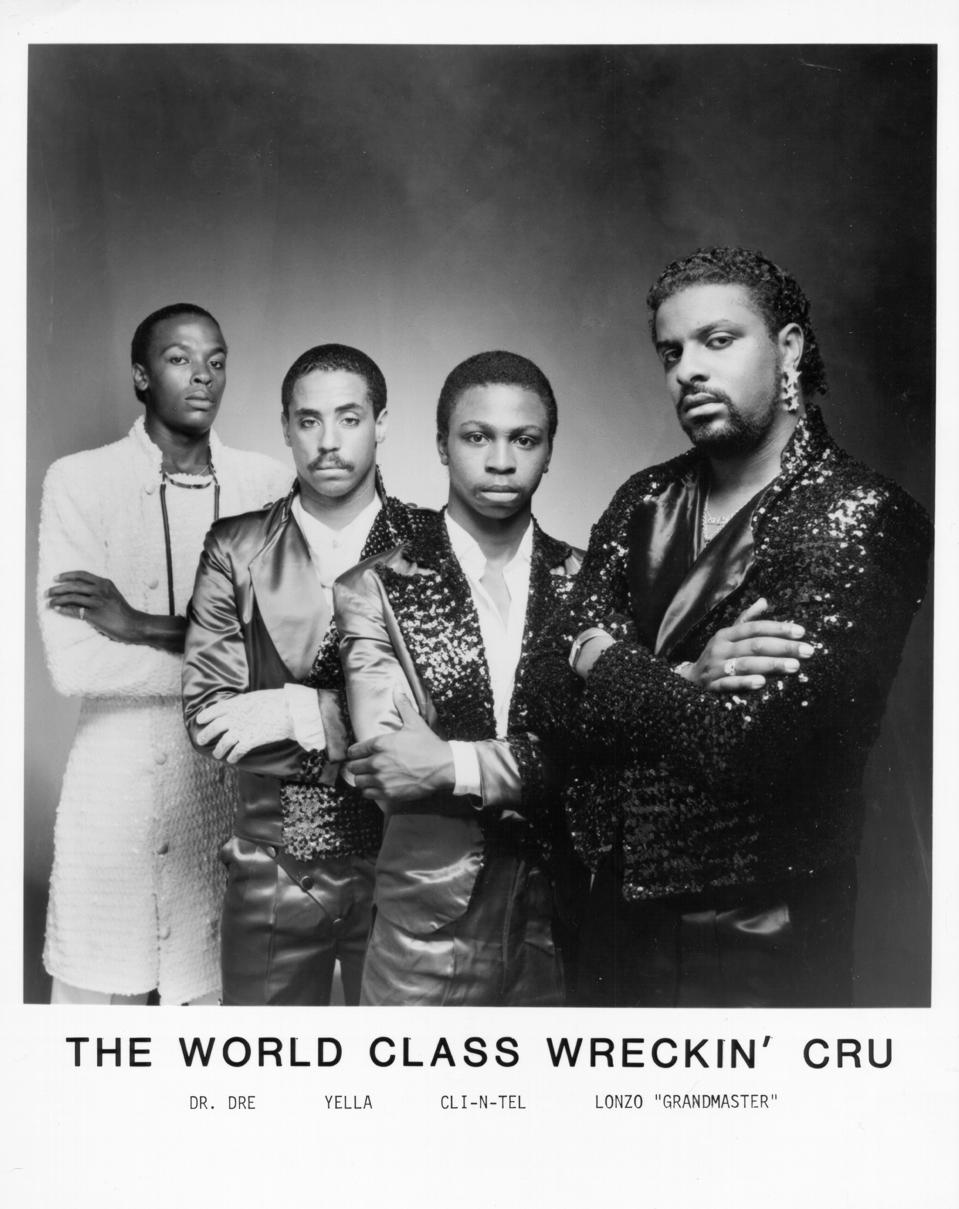

For music nerds, the musician also intricately details the origins of his DJ career and technological innovations in real-time, mapping out the path he and his contemporaries took to their gangster aesthetic. Spoiler alert: the origins of NWA are intertwined with the much more delicate image of the World Class Wreckin’ Cru.

Below, DJ Yella discusses the rise and breakup of NWA, the death of his pal, Eazy-E, and the staying power of the group’s most controversial track, “F*ck The Police.”

Given the struggles you’ve outlined, it's a miracle that you are where you are today. You were in the biggest group in the world, then eventually things changed and you hit your self-described rock bottom. Now you’ve written a book. You were immortalized in Straight Outta Compton and inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Before the pandemic hit, you were literally traveling the entire world playing shows. You’ve had your share of extreme highs and lows.

I tell people all the time, how many groups break up when they're number one? I don't think it's ever happened. And this is the part—you break up at number one, but the group is not mad at each other!? So evidently, there's some outside influences. Always the outsiders looking in, what can they get? That's what happened to us. It wasn't the group mad at each other, pointing fingers. No. We never had arguments, nothing.

What would you hypothesize the outside influences could’ve been? Someone telling another member that they could be way more successful if they went solo?

I don't know what was said. I'm quite sure it had to be stuff like that. But that's what broke the group up. It wasn't the inside, not at all.

In the moment when NWA ended, you talked about being stuck between a rock and a hard place. Dr. Dre called you and asked if you were coming with him, and you said that you didn’t know what to do, so you just didn’t make a choice...

Yeah, that was my answer. I didn't know what he was talking about until the next day or something when Eazy told me that he was gone.

It's early in the morning, I’m like, “You're going where?" I'm thinking the studio. But yeah, I was caught. I didn't answer. I was good with both sides, that's the problem. I was young, naïve. I didn't answer. And then by the time I could have answered, too late.

So by default, you were then with Eazy-E and working on Ruthless Records and that became your immediate future. Then, the world tragically loses Eazy in 1995 due to AIDS-related pneumonia. You had inadvertently chosen your path, now you were alone and the other guys had moved on. Did you feel like, “Well, what now?”

Yeah. I remember when they buried him and they put the dirt on top of him and then everybody left, I said, "I'm done with music." The music just went out of my body. That's it. I’m gonna do the adult films all the way, 100%. That's when I started putting my name and face, using my likeness and everything.

But a year later, somebody wanted a solo album and for me to finish Eazy's album and the greatest hits. But that was it for music. I didn't listen to hip-hop. If I listened to music, it was old stuff that's already been out from the early 90s and 80s. I didn't listen to the new stuff.

I jumped into the movies like a producer making songs and albums. I didn't think of it as girls and thrills. It was business. I didn't even have time to think about that. Never sat there like, "Oh, I should have went with him." Not one bit.

That’s an interesting point. You seem to be at peace with your life as you look back on it, stating that God has had a path for you. You went to work with Eazy and never could’ve known that he would die so suddenly. There was no guarantee that Dr. Dre would be so successful, either.

In your book, you describe when you were struggling the hardest, around 2010, you were homeless, staying with friends and family and sleeping on a slowly deflating air mattress in the projects. At no point did you compare yourself to others.

Meanwhile, Ice Cube was a successful rapper and went on to be the star of action and children’s movies. Dr. Dre had built an empire with Aftermath Records and Eminem. Then he hit billionaire status with the massive success of Beats By Dre. Was it hard not to be envious or compare your path in that period?

You know what the craziest thing is? I never knew about the headphones until Dre gave them to me. I never even heard of them. Once I was in that lane of [adult] movies, I didn't look at music or hip-hop, nothing. I never seen Boyz n the Hood. I never seen none of that stuff. I never heard Dre's first album [The Chronic]. I never heard it.

I never looked at what they were doing. I didn't even think about it. I was thinking what I'm doing or where I'm going. It's just like everybody just went their way doing their own thing. So, I went my way. Even though I know I went down the wrong path. That wasn't the path I was supposed to go. I went down it for 15 years.

You described Eazy-E’s funeral in pretty great detail. You said there were police and helicopters hovering as you performed your pallbearer duty and carried his casket. That must have been a very surreal experience.

When you're at the grave site, you look up on the hill, it's all undercover cops. I'm just like, "This is a circus." Somebody told me to lead the way with the casket. As soon as I opened that door, it was like a movie. Wow! There were more people on the outside of the church than on the inside.

What emotions were you feeling in that moment? Were you overwhelmed? Shocked? Sad? In disbelief?

You know something? I didn't really get to feel anything. So much was going on, it's just you ain't had time to think about it.

Until everybody finally drifted away, it was only three or four of us there and I just said, "You know something? I'm done with music." Just like that. And people was like, "How could you just quit music?" I'm like, "I just did. That's it." I loved it when I did it, but that was all for me.

One thing I found strange about Eazy getting sick was that he left you out of the loop and you had to find out he was sick through your friend. Why do you think he kept that from you? Is it because you guys were so close that he couldn't break it to you or something?

I don't know. We would be shooting movies and every day my friend was going to the hospital—I didn't know that's where he was going—every day for like two weeks to Cedars-Sinai [Medical Center]. I didn't even know he was going to visit anybody. He'd just leave and said he was going home, but he was going to the hospital every day.

[Eazy] just didn't want me to know. I don't know if he was embarrassed or what. He would be in a dark room with all the curtains closed—my friend would come there, open up the curtains, say, “Get up! We can fight this!”

He was talking normal all the way up until the day he had surgery. They put him in an induced coma after that. It wasn't like he was under the influence, none of that. Whatever happened in them two weeks while he was there, he was wide awake. I guess he just didn't want me to know.

You said that he gave you some sort of warning message that something bad was going on, but he was really mysterious and unclear about it, right?

When I was shooting [adult films] at his house, he called me on the phone, he told me, "Watch yourself."

I'm like, "Okay..." But he said that a few times. I didn't get what he was talking about until after the fact. Like, “Watch the girls…” that's what he was telling me. But he just didn't say “protect yourself.”

These days, people would just say, “Hey, you need to be careful about your sexual partners and use a condom.” But I’m guessing he was just incredibly vague.

Yeah, very. He just said, "Watch yourself." I didn't get it until then it was too late.

Did Eazy appear sick to you during the last few times you saw him?

No. I heard about him being in the studio when I wasn't there—he had bronchitis or asthma and he was coughing. I guess that was when he went to the hospital—he had a cough that he couldn't get rid of. But he never was sick. In the book, I got the two last pictures of me and him. One a year before at my birthday party and one the year later. You can look at the pictures, in the last one, he was way smaller than the year before. I didn't notice that until I held both side by side.

On a much lighter note—and a fond but funny memory you have of Eazy—you described how he was constantly on the phone. When you drove around, his car was always stocked with coins so he could use a payphone. Do you think if he was around these days that he'd be one of these people who can't put his iPhone down and glued to Twitter all day?

Yeah because his son is like that! That was when payphones was on the corners. Every few blocks, he'd get a page, because he didn't have a phone, he'd go to the phone booth. Get a page, go to the phone. A 25-minute ride to Hollywood would take us two hours—no traffic! That was funny. That was in the early days. His son is just like him. You know a real texter, they be going fast!

It seems like just talking about your friend brings a smile to your face. I’m glad you feel that way after all these years.

Oh, yeah. People think he was just hardcore. Yes, he was hardcore but not “killing hardcore.” That was his look. But he loved people. He really loved kids. He liked helping kids. I guess that's why he had so many.

You guys even had a Make-A-Wish type visit in the studio, right?

That was incredible—that their wish was to be in the studio with us. I'd never heard of that before. I was just like, of all the movie stars, all the Michael Jacksons, it was us! I remember that day. That was amazing. See, that's the kind of stuff he liked: taking kids to Disneyland or Magic Mountain. He was a nice person. People really didn't know that.

And he was a great businessman—but the problem was the management manipulated him. He didn't even know what was going on. You know, if people had beefs about the manager, it wasn't that E knew about it. The manager was just slick by himself. He was outslicking him. It wasn't like him and the manager was in cahoots. No. I'm quite sure he signed stuff that he didn't know he was signing.

It seems like everybody in NWA had a problem with that, right?

Oh, yeah! We just didn't know about a bunch of things back then: publishing, writers, producers, artists, we didn't know all this stuff! We had to learn it on the fly.

Just imagine all this coming fast: gold record, gold record, platinum, triple-platinum. Coming back to back! We was like the brand new Motown. And it was coming so fast that we didn't even have time to do paperwork. We didn't sign any paperwork for NWA until the middle of the tour in 1989. But we had already went a few years producing. Eazy's album went gold, platinum, double platinum. J. J. Fad, gold single. We had no paperwork!

You’ve said that you’re convinced it was outside influences that were responsible for NWA’s break-up. You also argue that if the group had performed just a few more shows together, then maybe things would have stabilized and the group would have continued. Tell me what you think about that whole period. There was such a brief window where you became the biggest group in the world in a matter of months, right?

That whole span was about four years with NWA and Ruthless, three plus maybe. But I remember when we was at the tail end and me and Dre was staying in the studio or on the road performing. That was our life—performing.

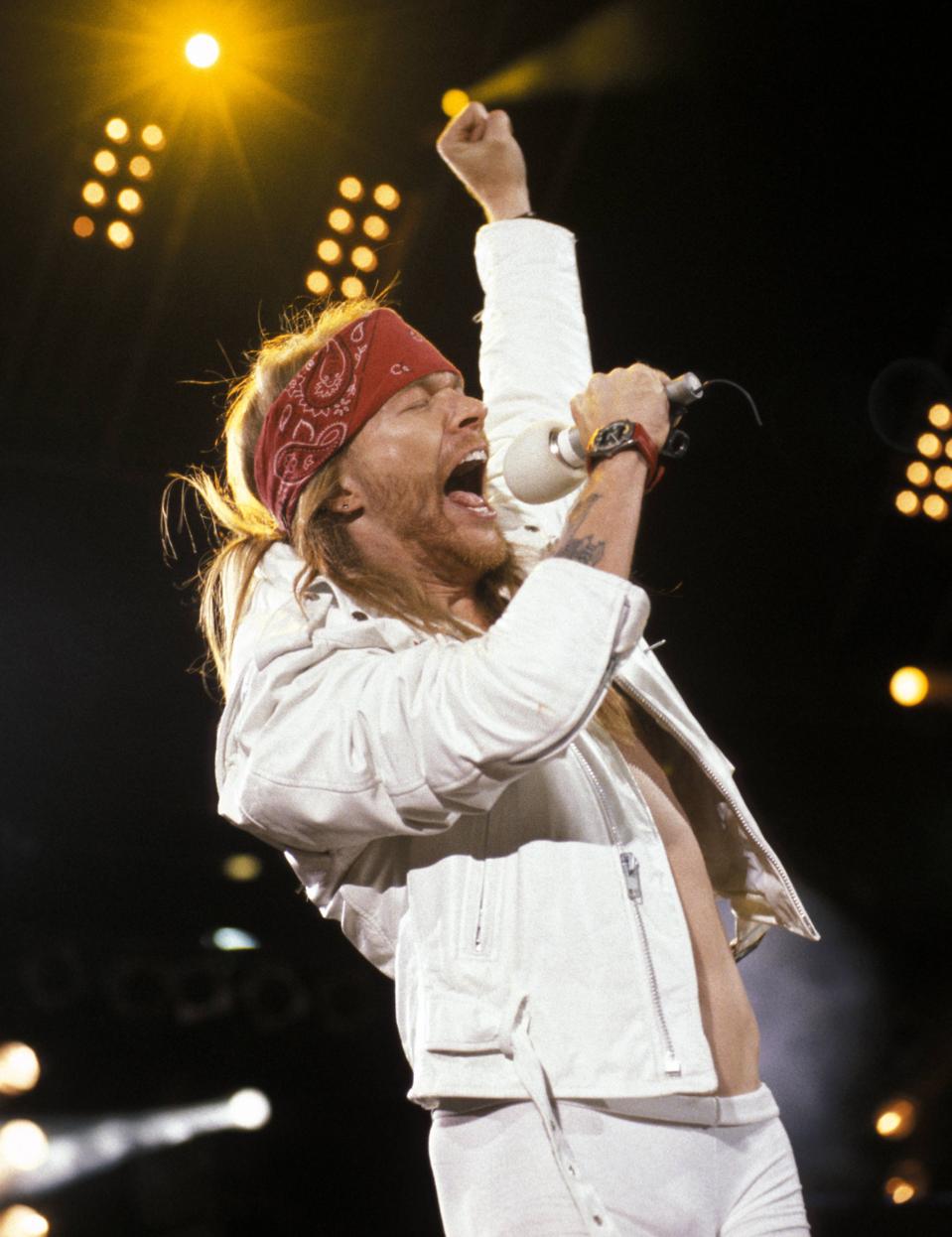

Guns N’ Roses wanted us to do a couple of shows and they did stadiums, they didn't do arenas! They wanted us to do two 10-minute shows, two or three songs maybe—that's it—for $25,000 back then! This was in 1991. That was a lot of money. But the manager was greedy. He wanted $50,000!

I think if we would have done them couple of shows and did well—because they did a whole tour for the next year or two, we would have been on that road—and nobody wouldn't have got to the inside [of the group]. That was me and Dre's world. We liked the road.

How weird would that have been if NWA and Guns N’ Roses toured together?

Well, think about it. You look at them videos from that time. Axl was always wearing our hat. He loved us. He wanted us on this tour.

Then we were supposed to do our second tour but the problem was we couldn't get insurance in the buildings.

Think about this. When we did the last album, we never performed no songs on that. We went to London and did two shows and that was the only time we performed. That was it.

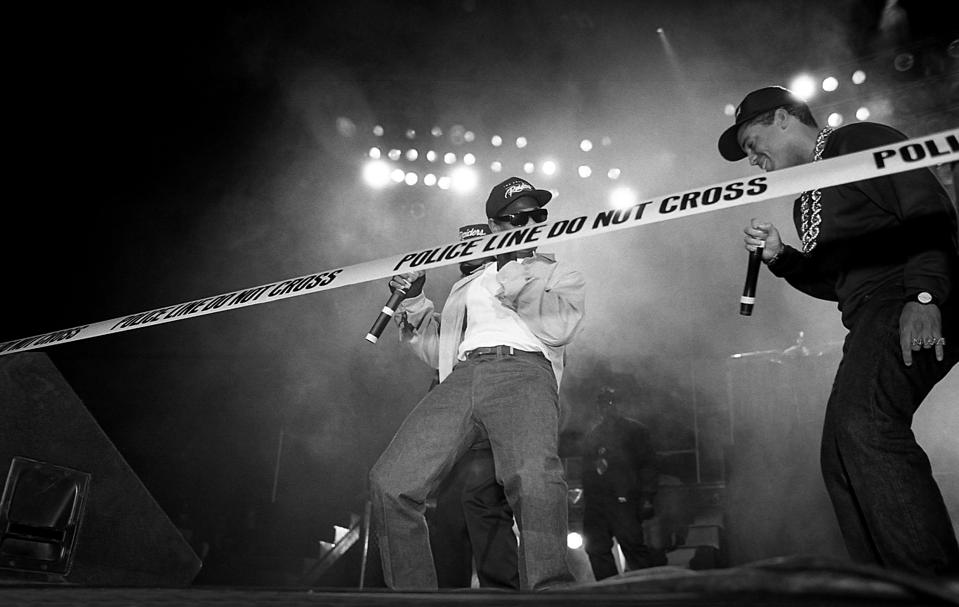

I thought it was interesting to read that on NWA’s original Straight Outta Compton tour, the group got an amazing reception in Nashville but you could hear crickets at The Apollo in Harlem. Wouldn’t you think New York City would be giving it up for rap music?

Well, New York was hard. They didn't like outsiders. We only did like two songs at the Apollo. I remember the “boo” word was at the tip of their mouth, but it didn't come out. They didn't boo us. People say that was a good thing, they didn't boo you. But man, that was like, when we were performing and it just felt like everybody had guns on them! [laughs]

Then Nashville sold out! It was like, “What's in Nashville?” The whole tour was like that. They would have no fights, no incidents, none. People that were on that tour, they still say that was the best tour of all time.

And Detroit was the famous gig where things went haywire because you performed “F*ck Tha Police,” right?

Yeah, because we weren't supposed to play the song. You know what's so crazy? Nobody knew about the song but Dre and Cube. They were the only ones!

E, Ren, nobody knew. When I heard them play it, I remember, I'm like, "No he didn't play this song!" We didn't even get halfway through Cube's verse before they started throwing—the police was undercover in the audience and they started throwing firecrackers and stuff. They just came towards the stage and we just ran. The thing about the movie, in the movie we got arrested and all that. We didn't get arrested.

We end up running to the hotel, got our bags, then we got in the elevator and guys turned around with badges. And then, they end up giving us $150 citations and asking for autographs.

Why did you agree to withhold the song to begin with? That doesn’t seem like you guys…

Because we couldn't get the buildings. I guess for the insurance, they wouldn't let us get the insurance. So, that's why we had to put groups like Salt-N-Pepa, Kid 'n Play, Kwame. We had to put softer groups to soften up our bill. And then we had to agree not to do the song. We didn't do the song nowhere except that night.

Did you ever think that “F*ck Tha Police” would become such a pervasive phrase in culture and protest? When you first said it, people were appalled, but now—while still divisive—it’s a commonplace expression. You certainly heard a lot of it during the recent waves of Black Lives Matter protests.

It's amazing. The first amazing part is we didn't invent it. That had been going on before us. We just happened to say it. That song was 30 years ahead of its time. At all the rallies it was the number one song. It was like the most downloaded during that period.

This song, we said this many moons ago. But what we talked about wasn’t Disneyland. We talked reality. In the ghetto, if there's three of us hanging out or driving, most of the time you're going to get stopped by the police for no reason, just because they can do that, because they wore a badge.

The crazy thing is we didn't say all the police was. It was only just a few. That's in any crowd. There's always knuckleheads. But it is so amazing that people can relate to that song that had never probably heard of it.

That song was made 30 years ago. This is what they used to do and that they're still doing. I’ve told this to people in a couple of interviews, but this is going to go on until some cop gets 100 years or something. Then it might start slowing down. You've got to pay for what you do instead of just all these unions sweeping it under the rug.

Think about it, how long they be getting away with this stuff with no cameras, no nothing for a long time! And even Rodney King! Somebody just happened to have a real camera. It's just been going on for so long. That song is still relevant.

You also mentioned Rodney King in your books while discussing the 1992 LA Riots. You said that when that went down, you were with Eazy and he was like, "Let's go out there and destroy some stuff!" And you talked him out of it. What went through your mind in that moment?

I don't believe in violence, I never have. That's just not my thing. Eazy would have been doing it just to do it, not, "All right, yeah. Let's go out and fight!" No. Because we wasn't political like that. None of us was.

Especially at the Rodney King one—everybody burning down their own stuff! The next morning when they’re wanting to go buy something from the store, it's all burned.

There are better ways to do it. But now, in summer of 2020 they found some better ways. You protest. You let the people know. You've got to let them know. There’s so much corruption in government.

But, it looked like we would have been out there burning the stuff. No, no. Just like the stuff we talked about in the raps, we talked about what we see or what we heard. We never said we went out there and murdered. Because you know you go to jail if you do that.

We were just like underground reporters. We just telling you this is our neighborhood, this is what we is. One thing about the ghetto, the ghetto is all around the world. Just different names. All around. New York, everywhere got a ghetto. And that's what we rapped about. We open our door, that's what we talked about, whatever's going on. We never talked about The White House. We don't know nothing about that. We knew what we knew. I guess that's what made us stand out because people can relate more. We talk regular talk—we just used fowl language.

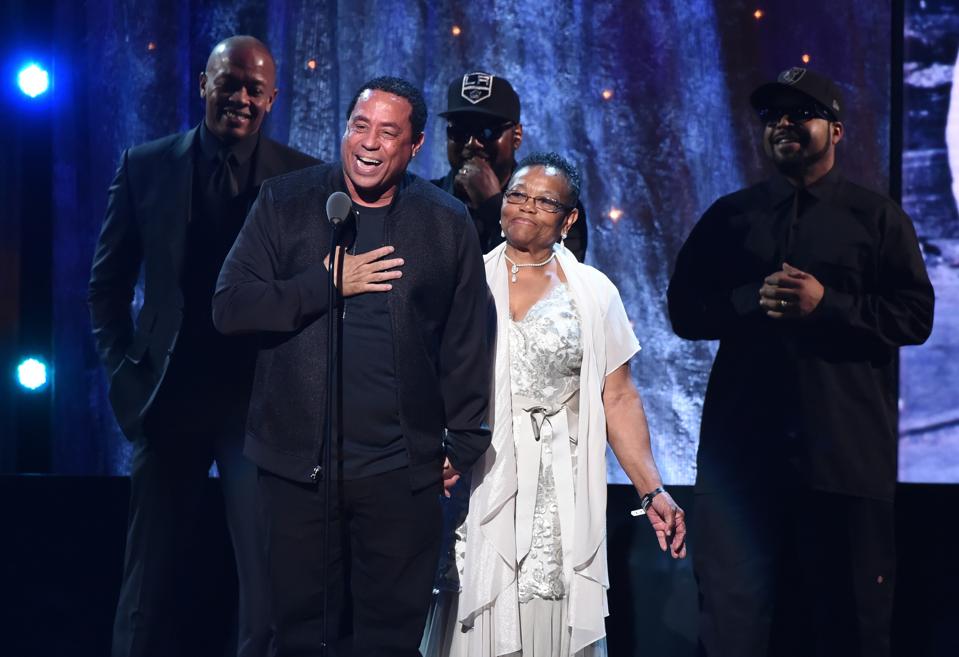

Final question: Why was it such a powerful moment for you when you were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

That felt pretty good. The best feeling at the hall of fame that night, I tell everybody let's take a quick selfie.

And I took that picture for that one second, that one frame you could look at all the smiles in there, it was all genuine. There was no managers, no agents, no security, nothing. It was just us in that picture. For a split second, it was just like 1989 all over again.

Pick up a copy of DJ Yella’s book, Straight Outta Compton: My Untold Story.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow me on Twitter at @DerekUTG.