In his glossy 2018 feature Loro, director Paolo Sorrentino offers a contentious depiction of the late media tycoon-turned-political heavyweight Silvio Berlusconi, largely echoing the stylish veneer adopted by the controversy-laden Italian mogul (writing in The Guardian in 2019, Peter Bradshaw described the film’s lead, Sorrentino’s frequent collaborator Toni Servillo, as ‘such a smart and sympathetic actor that he surrounds Silvio with an aura that he doesn’t deserve’). In his new monograph Televisiva, Stefano De Luigi assumes a different position, interrogating Berlusconi’s legacy by focusing on how his empire reshaped Italian TV, and subsequently infiltrated the premiership.

‘I was living in France, so it was “how can I explain, to a foreign public, how it’s possible that this tycoon is taking political power in Italy”,’ the photographer says today, recalling the project’s beginnings following Berlusconi’s initial ascent to power in March 1994, having founded the centre-right party Forza Italia just a few months prior. ‘I thought, as a photographer, I need a place, an environment, I need something visual.’

Working for foreign press gave him access to, and agency within, television studios (‘It was very easy, people were flattered’) and he began what would ultimately become a 15-year project documenting the country’s changing media landscape, and audiences’ complicity in it (the book’s scenes he describes as a ‘perfect mirror of society’).

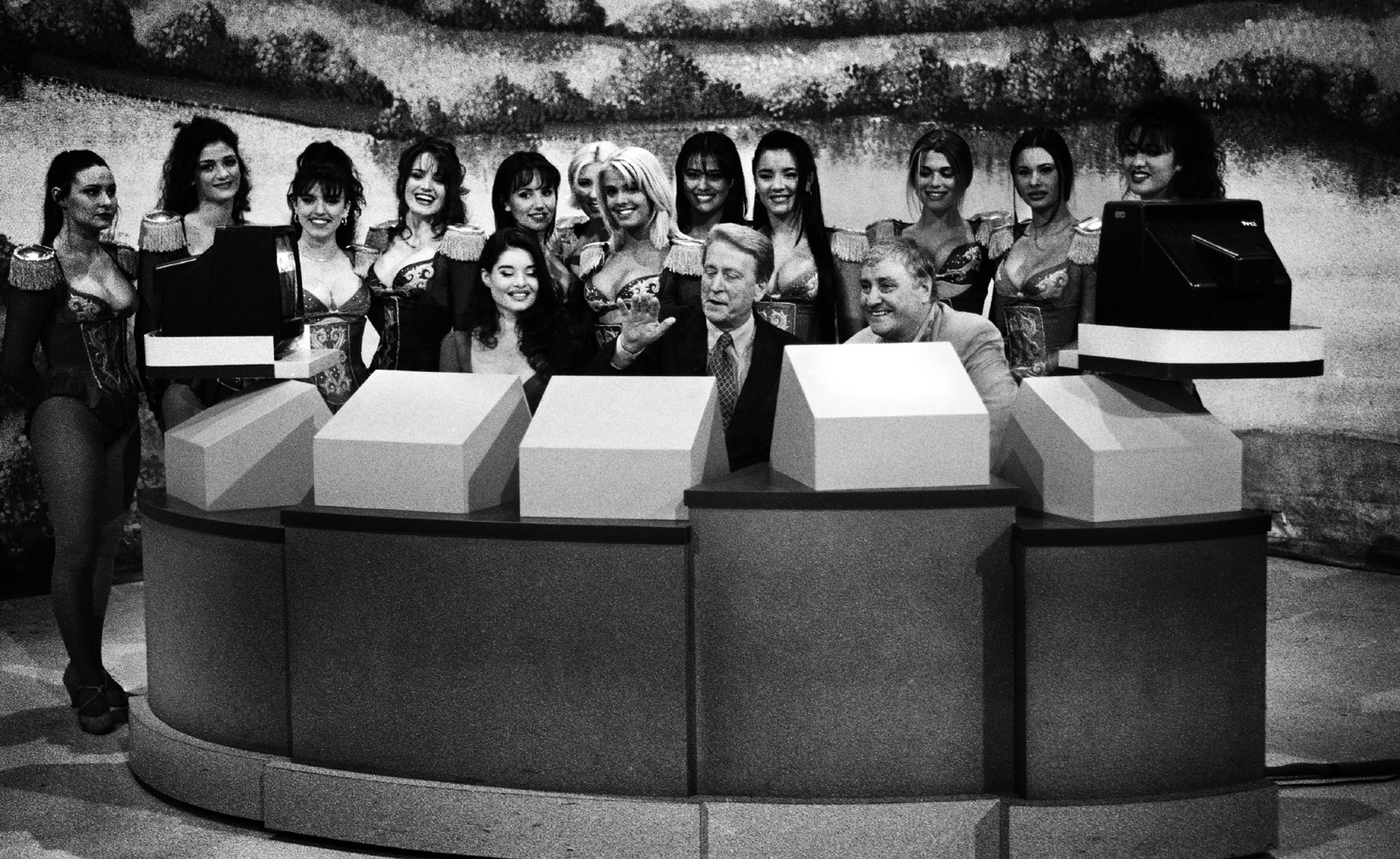

The images in Televisiva highlight a fashion for grossly decadent game shows

Shot exclusively in black and white, the images in Televisiva highlight a fashion for grossly decadent game shows: glamorous women, usually young and often not wearing much, are a frequent motif, while older men appear mostly in suits, others in some form of fancy dress. A further picture, rejecting these tropes, foregrounds the emergence of a new era in television, with a bare-chested man fixing his hair, a small microphone hanging around his neck. It’s a familiar sight for more contemporary audiences privy to shows like Love Island, but the young man here is one of the early contestants on Italian Big Brother, Grande Fratello. ‘I thought maybe I was ending the work in 2000, but then there was the first edition of Big Brother; a big change,’ shares De Luigi. ‘I thought, “It’s not the television anymore, going into the houses of Italians, it is the Italians going inside the television”.

‘You could really build your career… [Matteo] Salvini and [Matteo] Renzi, two main political figures in Italy, they started on game shows’

Stefano De Luigi

‘From 1994 to 2000 television was very divisive, as they introduced this “either you think like me, or you are an enemy [attitude]”,’ he continues, reflecting on the rise of Berlusconi and concurrently, this new perspective (by 2002, the mogul would have some form of control over 90 per cent of Italian TV). ‘There was no space for critical thoughts. What we could see on television then in Italy was this new spirit, of freedom and expression – the terrorism years were not so far away – so this kind of programme, very light and amusing on the surface [became popular].’

The photographer, however, argues that it pushed an agenda, presenting women like furniture and adopting a type of vulgarity he found tough to navigate. This opinion proved an anomaly: many others were encouraged to appear on TV as an avenue for professional opportunities. ‘You could really build your career – one Big Brother participant [Rocco Casalino], for three years he was the spokesman of the government,’ notes the photographer. ‘Today it’s the same, [Matteo] Salvini and [Matteo] Renzi, two main political figures in Italy, they started on game shows.’

De Luigi’s decision to shoot solely in black and white was a responsive one, employed to create distance, he explains. ‘These television shows were very colour-saturated – I wanted people to understand what they were watching. [With black and white] suddenly they describe another world, much more pathetic, more violent and pornographic; if you were watching in colour it was like a circus. It was very Fellinian somehow, but for me the message was horrible.’

Similarly, publishing the photography book now, more than a year since Berlusconi’s passing, was a conscious choice and one that De Luigi hopes will provide a greater historical lens, additionally underscoring the parallels between Berlusconi’s trajectory and more current political figures. ‘These pictures aren’t immediately connected to a folkloristic character like Berlusconi, they can be understood by many,’ he offers. ‘I was a privileged observer, because I was living outside, I could really watch what was going on then. I was in the right time, the right place, so I worked on this subject because I was really concerned. I'm still concerned, somehow.’

Televisiva by Stefano De Luigi is published by L'Artiere, €55, lartiere.com