Sometime around 100 AD, the Roman lawyer and aristocrat Pliny sent a letter to his third wife, Calpurnia – who was staying in a different part of Italy – to express how much he loved and missed her:

I love you so much, and we are not used to separations. So I stay awake most of the night thinking of you […] The only time I am free from this misery is when I am in court and wearing myself out with my friends’ lawsuits. You can judge then what a life I am leading, when I find my rest in work and distraction in troubles and anxiety.

Most people living today have felt some form of passionate romantic love, or will at some point in their lives – often with heartbreak in equal measure.

When we have problems with love, we like to console ourselves by thinking this happens to many other people. This is certainly true.

It has, of course, been happening for thousands of years.

Why do we fall in love?

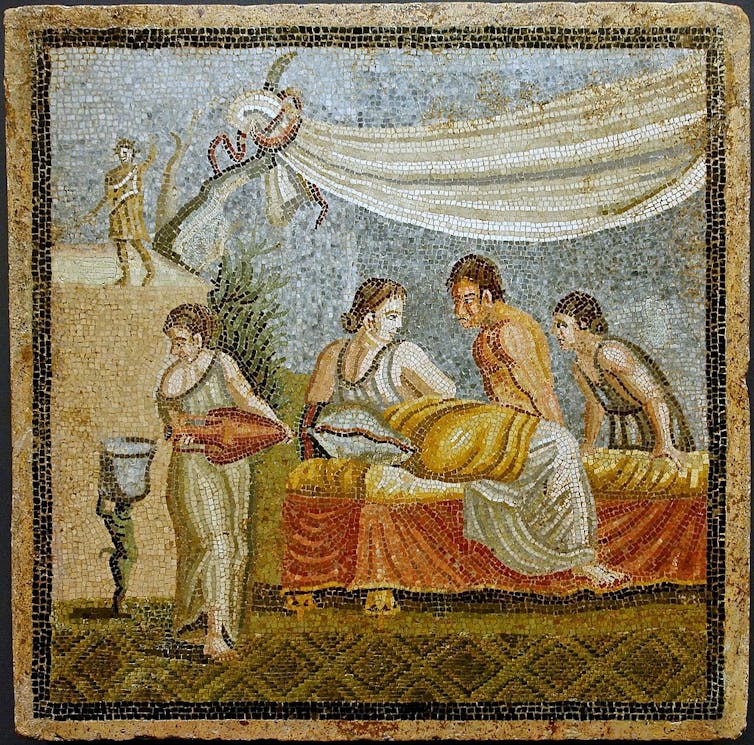

One of the most famous ancient accounts of passionate love is found in the writings of the physician Galen (126–219 AD) who worked in Rome. In his book On Prognosis, Galen describes how he paid a call to the house of a man whose wife seemed unwell – suffering from insomnia, yet not with fever.

Galen questioned her, trying to find out why she couldn’t sleep, but she was unresponsive:

She replied hesitantly or not at all, as if to show the folly of such questions, and finally turned over, buried herself completely deep in the blankets, covered her head with a small wrap, and lay there as if wanting to sleep.

On subsequent visits, he discovered the woman was in love (and infatuated) with a dancer called Pylades, whom she had seen dancing at the theatre in the city. Her poor condition came from knowing her love could never be more than a secret desire.

Ancient people recognised how love could occur seemingly randomly, for reasons both simple and complicated.

In a play called The Man Who Loved Musical Pipes by Theophilus (4th century BC), one of the characters explains his basic reasons for having fallen in love with someone:

As for me personally, I’m in love with a young woman who plays the lyre […] she’s pretty, she’s tall, she’s good at her job.

Ancient lovers’ passionate embraces and affections have sometimes been recorded in intimate detail.

In one anonymous poem (of uncertain date), the author describes how, after his lover won a boxing contest, he went and kissed him on the lips even though his face was covered in blood:

When Menecharmus, Anticles’ son, won the boxing match, I crowned him with ten soft garlands, and thrice I kissed him all dabbled with blood as he was, but the blood was sweeter to me than myrrh.

The difficulties with love

There are many Greco-Roman stories about unrequited love and the miseries it can bring.

According to the philosopher Aristoxenus (4th century BC), one woman named Harpalyce died of grief after she fell in love with – and was rejected by – a man called Iphiclus.

There are also stories of people struggling to be with (and stay with) their lovers.

Galen explains how one of his patients, a slave, pretended to have a knee injury so he wouldn’t have to travel away from his lover for work.

Elsewhere, Galen writes about people engaging in secret love affairs:

They often have sex when they are drunk or have not digested their food, and they often engage in secret affairs so no one notices.

He says, with dry humour, these “secret affairs” are the reason “the similarity between children and parents in humans is less pronounced”.

Spouses also bickered back then, much like today. In a letter from around 200 AD, a man travelling in Alexandria, Egypt, wrote home to his wife to complain how she didn’t seem to care much about him:

sleep does not come to me at night because of your inconsistency and your indifference concerning my affairs.

Is love a sickness?

Some ancient doctors thought love was a major factor in determining a person’s mental and physical health.

Galen, for instance, believed love could be blamed for some of his patients’ ailments.

I know men and women who have been struck by passionate love and become despondent and sleepless, then contracted an ephemeral fever because of something other than their love […] The disease of people who are constantly thinking about love is hard to cure.

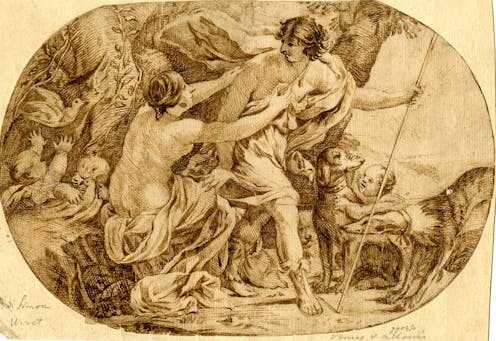

Galen recommended people with lovesickness should change their lifestyles and engage in bathing, drinking, horse riding and travelling. He also advised them to invest their emotions into other matters such as gladiator fights or hunting with dogs.

Other doctors thought love was so powerful it could potentially cure people’s psychological problems. The 5th-century physician Caelius Aurelianus said love could be both the cure and the cause of insanity.

Either way, there’s no denying it

In one of his plays, the influential playwright Antiphanes (active in the early 4th century BC) wrote:

There are two things a man can’t conceal: that he’s drinking wine and that he’s fallen in love. Because both conditions betray themselves from the expression on his face and the words he speaks. In the end, those who deny it are the ones they most obviously convict.

So the next time love is on your mind, take comfort in knowing you’re not alone. For millennia, people have dealt with this difficult emotion – in all its glory and calamity – and come out the other side unharmed. Mostly, anyway.

Konstantine Panegyres does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.