Rebecca Humphries rarely drinks, but she knows what dependence feels like. So she felt an instant connection with her latest character in the play Blackout Songs: an alcoholic barfly called Alice, who falls in love at an AA meeting.

“I know what it is to look outside of yourself for some kind of intoxicating substance, to help you either escape your reality or validate your low opinion of yourself,” she says, her pool-sized eyes looking out from under a fringe so thick it would make Claudia Winkleman do a double take. “I was in this really heady, toxic relationship with another person, and when I look back on it now, I realise that, actually, so much of my staying in something that I knew was hurting me, and draining me of who I was, was feeding my own insecurities. Just like alcohol does. Just like drugs do.”

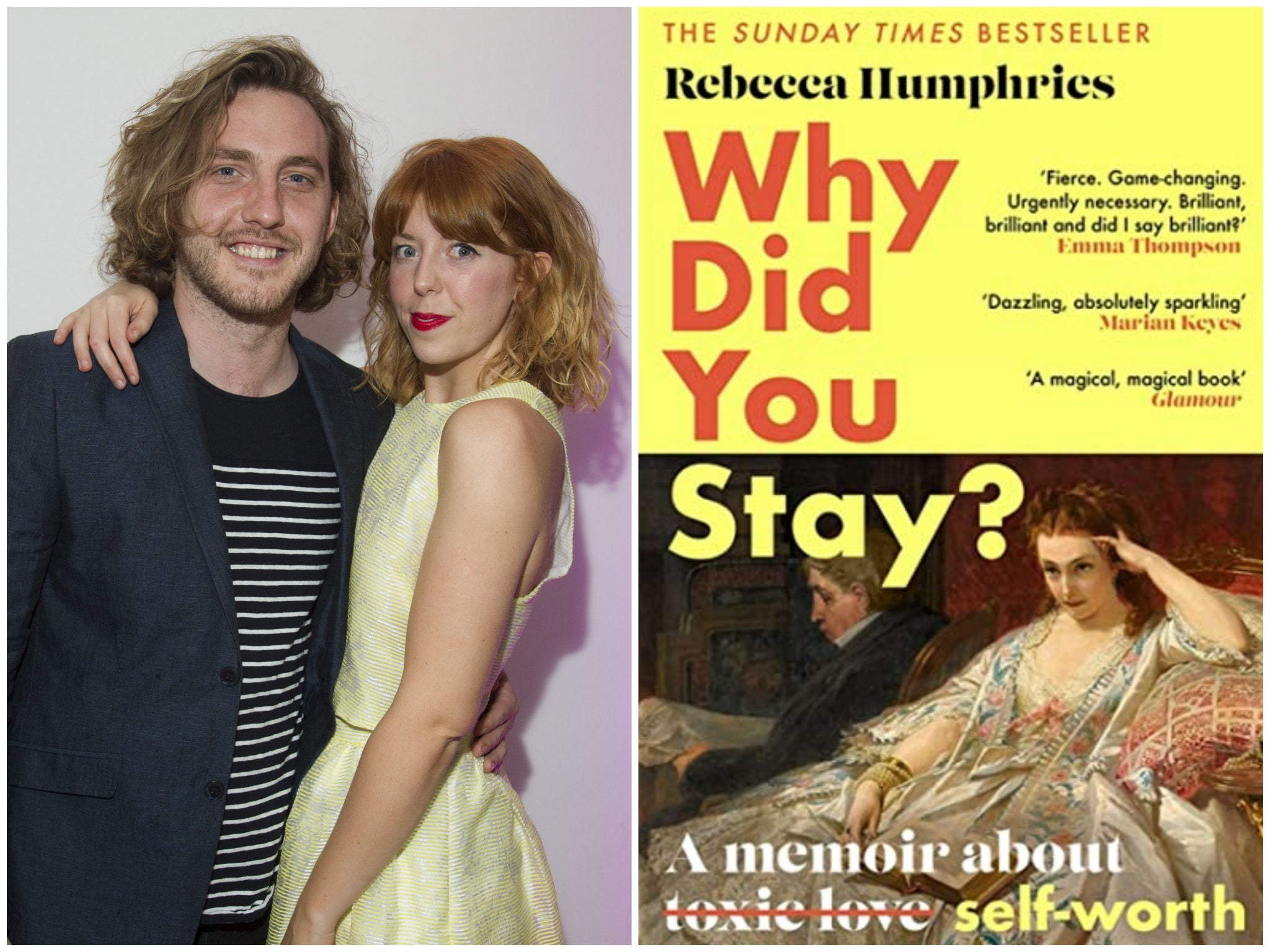

The relationship that Humphries is describing imploded in 2018, when her then-boyfriend, the comedian Seann Walsh, was filmed kissing his married dance partner on Strictly Come Dancing (more on that, and the book that Humphries wrote about the experience, later). Blackout Songs, written by Joe White and returning to Hampstead Theatre for a second run tonight, stars Humphries as a smart, staccato, sweary, wise-cracking hot mess, who talks filthily about everything from sex (“I’d shag him rotten”) to her father’s death (“His liver exploded, basically, hand grenade in him, finally f***ing popped”). After Alice meets fellow addict Charlie, the pair form a wild, passionate bond. “The play is so much about dependency,” says Humphries, “but the surface layer is alcoholism and the deeper layer is one another. And the problem is that those dependencies get intertwined, and so they start to associate one another with the booze, and before you know it, they don’t know which one they love more.”

Blackout Songs runs at 90 minutes, and Humphries is never off-stage. “It’s intense and unrelenting,” says the 35-year-old, sitting at a street table outside a Covent Garden café. “There’s something really freeing about that, because it’s like being strapped in on a very fast, quite dangerous fairground ride, and then suddenly it’s over and you’re like, ‘Oh, wow, that felt about 30 seconds long.’” Being with Humphries feels a bit like that, too. While she sits quite still, her chin cradled in a perfectly manicured left hand, she speaks in fast-flowing rivers of emotion and humour. Conversation topics ricochet from what she calls her “media scandal” and the gossip she had with her hairdresser that morning, to her latest bargain – her leather-look fur-trim coat. “Thirty pounds! From New Look! Who knew? Been knobbing around in Liberty’s this whole time…”

The play takes its name from the experience of blacking out when drunk – something Humphries recalls happening as a teen following a youth production of The Sound of Music. “I was like 17,” she says, “and it was an after-show party – it’s always the most wholesome, virginal productions where you got the most f***ed up afterwards. It was those salad days of Skittles vodka and jelly shots. And if you fancied someone you got annihilated, because it gave you all this courage. I woke up the next day and didn’t remember anything. That was my first white-as-a-sheet, I-never-want-people-to-inform-me-of-my-own-actions-again moment.”

Humphries – who studied at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (Lamda) and went on to star in acclaimed plays such as Temple at the Donmar Warehouse, and Pomona at the National Theatre – says that Blackout Songs has made her really think about the drinking culture of the UK. “Alcohol, drugs, exercise, spending money, being in love with people who hurt you – all of these things exist so that we don’t have to confront what’s happening in the moment,” she says. “And, let’s face it, the UK feels, at times, like a bit of a bin. Prioritising pleasure and feeling joyful actually feels increasingly difficult. And so the easiest thing to do is just blackout, you know?”

The play is a subversive take on the romcom, a genre that Humphries says “has a lot to answer for”. “In romcoms, narratives have to have difficulty for there to be a story. So you have to overcome, overcome, overcome – but it’s a mistake to think that that should replicate real life,” she says. We’re interrupted by the sound of Kesha’s “Die Young” blasting out of a speaker on a passing rickshaw. The women who’ve hired it look sort of distant and sad. “I’m sorry. Obsessed,” says Humphries, enjoying the music. “This is the bit in the romcom where I walk off down the street after my interview. Anyway, what I was saying was that there’s always stuff in life to overcome, but that shouldn’t be in your love life. If anything, your love life is there to help you overcome, it’s not there to be the problem you have to solve every single day.”

Since her split from Walsh, Humphries has learnt that it’s fine for relationships to just be good. No fire. No drama. There was a lot of fire and drama, it seems, with Walsh. Their relationship ended after pictures were splashed in the papers of him cheating on her, on her birthday, with Strictly professional Katya Jones. After the story broke, Humphries tweeted a statement that began, “I am not a victim.” She claimed that, during their five years together, Walsh had called her “mental” and “psycho” whenever she questioned his behaviour. She signed it off with a defiant “I’m not sorry I took the cat”.

My idea of love has changed shape entirely

Then Humphries wrote a book about it, Why Did You Stay?, the prologue of which reads, in part, “To anybody that feels this book has been inspired by their actions, I would just like to say: I am sorry if what I’ve included makes you feel bad. But I humbly accept your gratitude for the things I have graciously opted to omit.” The memoir – funny, visceral, bruising – chronicles every moment in forensic detail, from Walsh coming clean and the burning flash of paparazzi cameras, down to the private texts she received from Jones. It’s also a study of toxic relationships and a campaign on the importance of self-worth.

Has Walsh read it? “I have no idea,” Humphries says, smiling. “Absolutely none. He’s done maybe two or three stand-up shows about the whole incident, and I’ve never watched them. So I guess we’re just on our own trajectory, doing our own thing, and to say that’s fine by me would be an understatement.” She didn’t watch Walsh on I’m a Celebrity, so missed out on witnessing his bromance with Matt Hancock. “No, I was busy doing a five-star play,” she says, with clear relish and a big “ha!”. “I didn’t engage with it – for me to have watched it would have felt like going backwards a really long time, and I have no interest in that.”

Humphries had been working for a long time before the fall-out from Walsh’s affair. In 2014, The Guardian’s Susannah Clapp wrote of her performance in Alistair McDowall’s dystopian drama Pomona, “Amid a top-notch young cast, Rebecca Humphries, sullen and wary, is outstanding.” But Humphries says she has had a much better relationship with her job since 2018 and the “visceral” lesson it taught her. “Before the whole media scandal, it had been really important to me that I projected an image of success – whether that was if I had high-profile jobs or a very successful boyfriend or important friends – and then when it all came crashing down, I was left with really not very much at all,” she says. “And that’s when I found my voice.”

She says her “idea of love has changed shape entirely”. “I used to equate passion with danger… but actually what you don’t realise when you’re younger is that it’s not love that you’re associating with passion and danger, it’s risk and reward,” she says. “So when you’re let down by someone and then they grovel and tell you that they need you, that’s not love that you feel in your body, that’s relief. I used to think that my body felt like it was filled with love when I would get kicked off a 30-storey building and get caught an inch above the pavement.” I tell her it’s a punchy analogy and she admits, with a cackle, that she is quoting her own words from her book. “Gross!” she shouts.

Humphries is glad that Blackout Songs came along when she was in a better place. “I’ve been up for countless roles in my career where I’ve been living the experience simultaneously to the character that I’m going up for and it’s not healthy,” she says. “You’re taught that your fragility and rawness are what make you a good artist and a good actor. But it’s very dangerous, actually, to put all of that out there… and you can protect yourself and be really good at your job.”

When she was writing Why Did You Stay?, Humphries was playing a role very far from her real life – as an assistant at a talent agency who has an intense crush on her boss, in the TV show Ten Percent (the UK version of Call My Agent!). However, incredibly, she was literally writing the book while the cameras rolled. “The production team hooked me up to WiFi so that I could write it on a Google Docs,” she says, gleefully. “In between scenes, I was just carrying on as though I was Day-Lewis or something, really serious, and then Helena Bonham Carter came up to me and was like, ‘You look very plausible!’ I was like, ‘I’m not that woman, I’m not getting bang into my character, I am just writing this book.’”

Humphries is writing again now – a TV series with Blackout Songs playwright White, and a novel of her own. “I’ve been threatening to write a novel for f***ing ages,” she says. “It’s far more epic and is going to involve a lot more world-building than I’d planned, but I’ve never gone about anything tentatively, good or bad, in my career or in my personal life.” She laughs. “So why stop now?”

‘Blackout Songs’ is on at Hampstead Theatre from 8 April to 6 May