Up until the 1968 Olympic Games, Dick Fosbury was mocked. His unusual high-jump style, attempting to leap over the bar with his back arched, caused him to be dubbed cruel names by the US media. “The laziest high-jumper in the world”; “a fish flopping into a boat”; “a two-legged camel,” referring to his jaunty run-up. The Los Angeles Times thought he looked like “a guy being pushed out of a 30-storey window”.

But Fosbury’s ability to harness their words and channel them into something positive was one of his many strengths. “As an athlete you’re a performer,” he said. “All of us doing sports, we love attention. So if you’re getting some attention – even if you’re being laughed at – that’s a good thing. I took it as they were not ridiculing me but enjoying something radically different.”

One criticism did sting. Fosbury, who has died aged 76, was only 21 when he reached the Mexico City Olympics in ‘68. His technique was the talk of the track, and a couple of revered German coaches took it upon themselves to pull him aside and deliver a hard truth: for as long as he continued using that maverick style, he would never succeed at high jump. He told them: “I’m going to use what I’ve got, and we’ll see the results.”

Five years earlier Fosbury had been ready to give up the sport. He was struggling with the on-trend scissor technique, and when his high-school coach encouraged him to try the more traditional ‘Western roll’, results got worse. He decided to try one more track meet, with an adaptation of the scissor jump he had been working on in which he raised his hips over the bar, and that day the seeds of the Fosbury Flop were sown.

The method immediately added several inches to his personal best and, four months before the Olympics, a relatively unknown Fosbury won the US national college championships. There were still doubts about his technique and concerns were raised over safety, with good reason – foam mats were not yet widely in place for the high jump and Fosbury damaged his spine, significantly enough to avoid conscription to war in Vietnam. But he ignored the scepticism, not least of his own coach, and won the Olympic trials two weeks later to earn a surprise place at the Games.

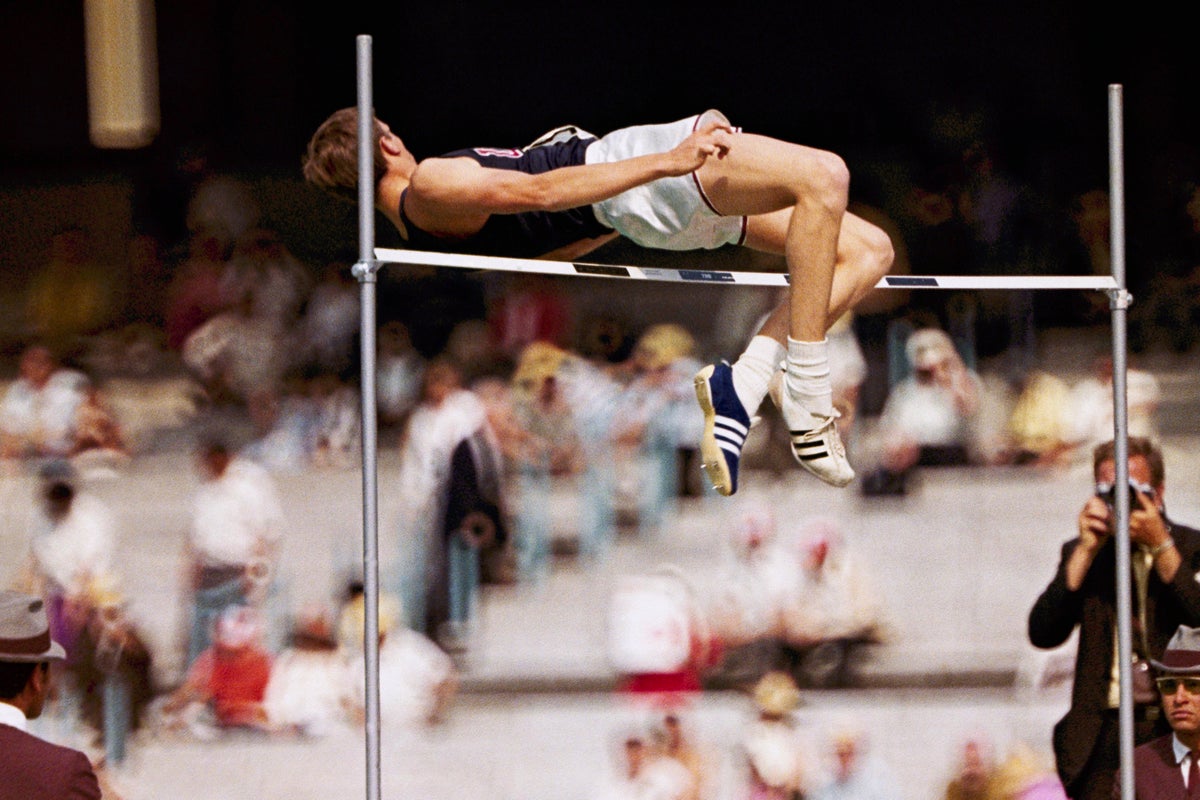

The spectators on that October day in Mexico City were rapt. Fosbury knew how to work a crowd – he was a performer in his own eyes, after all – and he would build them into a frenzy before showing off his trick, so that when it came to the decisive moment the entire crowd was willing him to succeed. “By the time we reached the gold medal height, everyone in the stadium was silent,” he remembered. “Once I cleared it with space between my body and my bar, I’ll never forget that feeling.”

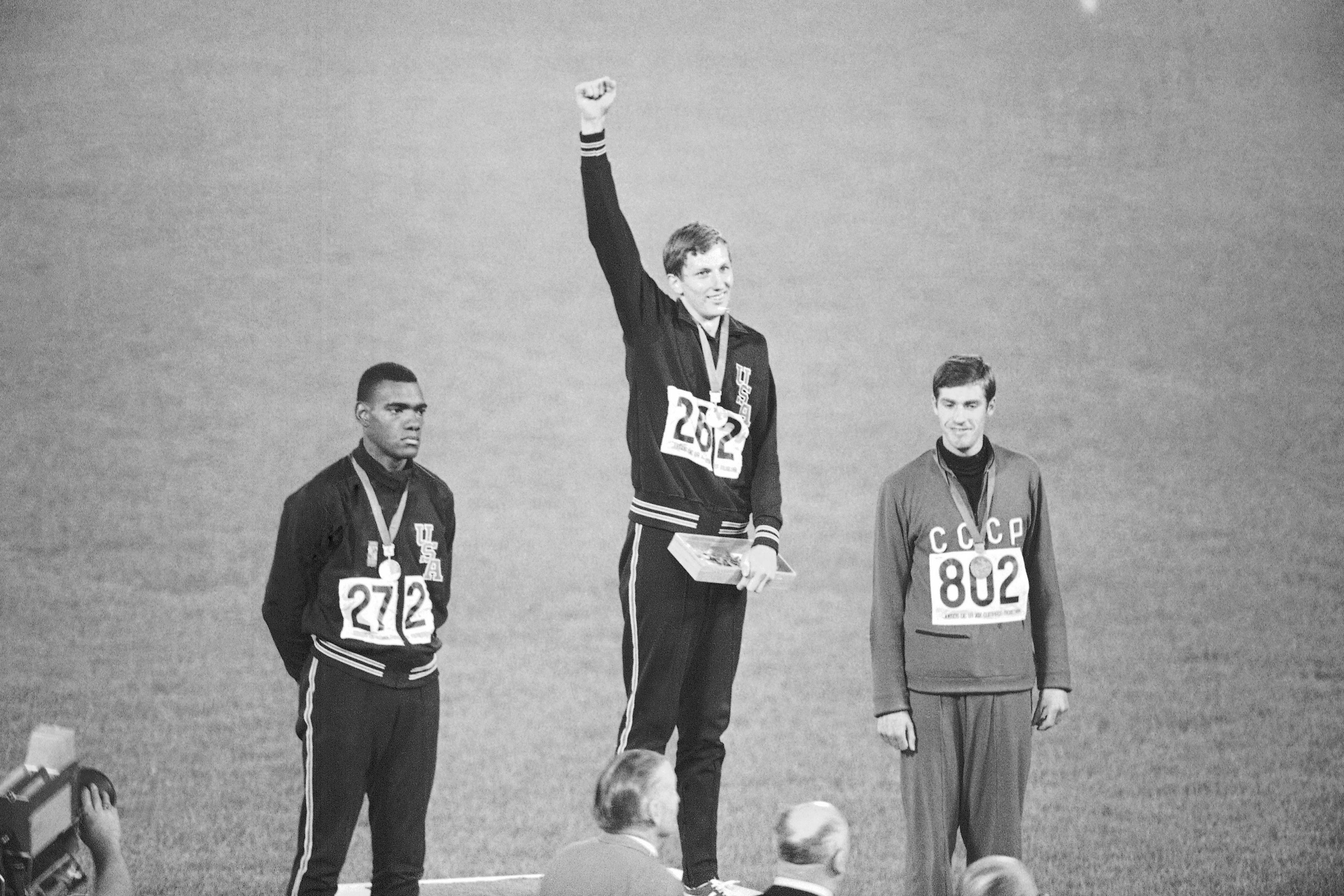

Fosbury’s shock gold medal was a story of innovation and ingenuity, but also one of daring to be different – of what can happen when you ignore what other people think. Fosbury was not like the others; this was a man who had missed the opening ceremony to drive out into the desert on his own and watch the sun set. High jump’s revolution required a man to hear his critics and do it anyway.

Even after winning Olympic gold, many of his fiercest rivals continued to shun the Fosbury Flop, and it was only those younger jumpers or those on the fringes of the elite who embraced this new idea; it took a generation to fully take hold of the event.

Fosbury’s story brings to mind Wilt Chamberlain, one of the greatest NBA players of all time, but whose free-throw success was woeful. For one season Chamberlain switched to an ungainly underhand technique and his scoring percentage shot up. But the “granny shot” drew derision and he stopped, and returned to struggling the traditional way. Chamberlain even hired a psychiatrist, who worked with him intensely on the court on the traditional method, but to no avail. “After a month, the psychiatrist was a better free thrower than I was,” he joked.

Pride got in Chamberlain’s way, but despite the attempts to ridicule Fosbury, he never wavered. There is an irony, then, that it wasn’t the doubt but the glory which knocked him off his stride. Fosbury liked attention but only up to a point, and he soon discovered he preferred punching up, not looking down. “I didn’t want to be on a pedestal. I received my medal and I wanted to be back on the ground with everyone else.”

He retired after failing to qualify for the 1972 Olympics and studied engineering, a fitting topic for a man who rewrote the mechanics of his sport. His legacy lives on: the high jump provided one of the iconic moments of Tokyo 2020 when two rivals, Mutaz Essa Barshim and Gianmarco Tamberi, agreed to share gold, and both won it deploying the Fosbury Flop, of course. “I never imagined that it would become universal,” he once said. Fosbury was humble as well as talented, but mostly he was brave; the pioneer who turned cynicism into gold.