Convict Orphans has a long but apt sub-title: “the heartbreaking stories of the colony’s forgotten children, and those who succeeded against all odds”. And this is exactly what this beautifully written book is about.

Review: Convict Orphans – Lucy Frost (Allen & Unwin)

The history of the children convicts were permitted to bring with them, or who they gave birth to while under sentence, is one of the many recently discovered troves of human experience in our archives.

This history is possible first because of the astonishing detail of the government administration of the penal system; second because of the world-leading digitisation of historical archives and of the nation’s newspapers (known as Trove), which has opened our past to citizens as well as professionals; and third, because of a powerful grassroots army of researchers that Lucy Frost herself helped lead.

Together with the doyenne of Tasmanian local history, Dr Alison Alexander, Frost – then a professor of English at the University of Tasmania – founded the Convict Women’s Press in 2010, a not-for-profit publishing company run entirely by volunteers.

Not only have they published seven monographs, with an eighth coming out this year, but they started the Female Convicts Research Centre, which has led research into every woman transported to Van Diemen’s Land. An army of local volunteers has researched shiploads of women, and researchers from all over the United Kingdom have daily sent snippets to Hobart gleaned from local court records, county archives and prison registers. These snippets build ever-growing life stories of people once hidden from history.

Writing about them, however, brings problems lest one be accused (as a now-deceased publisher said many years ago of my PhD thesis) of writing a mess of biographical droppings.

The stories of boys and girls in Convict Orphans are moving, but there is not enough historical context and argument. Frost has organised her book with considerable artistry around scenes and locales that collect a handful of shared experiences among the lives she has researched. But while she alludes to more complex stories and explanations, there could be more of them.

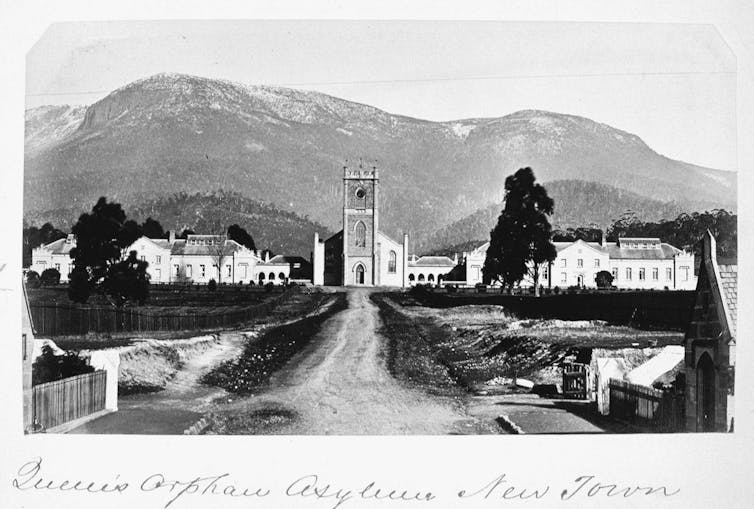

Convict Orphans tells the story of the 6,000 children who entered the Queen’s Orphan Schools in Tasmania between 1828 and 1879, yet few were actual orphans. Most were the children of convicts or, after transportation ceased in 1853, of parents unable to care for them because of imprisonment or mental illness or incapacity.

Many children arrived on convict ships with their parents, either a mother or a father, because the local parish would not care for them. Others were born to women under sentence and removed to the orphanage on weaning, whence they died in scandalous numbers from failure to thrive and gastroenteritis.

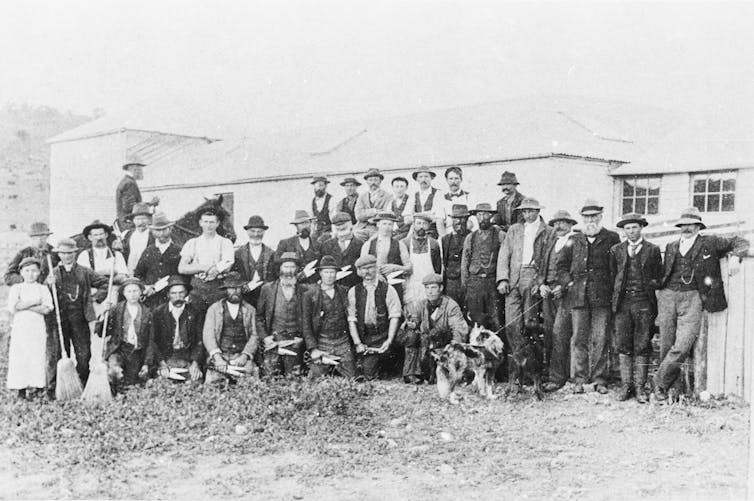

They remained in care and under instruction until the age of 12, when they were apprenticed out, and it is from these indentures that Frost has gleaned her stories. Thus the state remained ostensibly responsible for them until they matured as independent workers.

Gruelling work

Poignant moments bring alive the desperate struggle to survive for the genteel poor, in particular the widows who inherited debts and took to taking in lodgers. They saved paying wages for domestic help by using apprentices from the Queen’s Orphanage as domestic help. The work was gruelling for mere slips of girls. Likewise, boys were snapped up by dairymen and small farmers to provide free labour. Their living conditions could be gross.

The stories are not all grim, however. Some orphans were welcomed into households and a good relationship with a mistress or master could provide the first step into adult independence, marriage and a family.

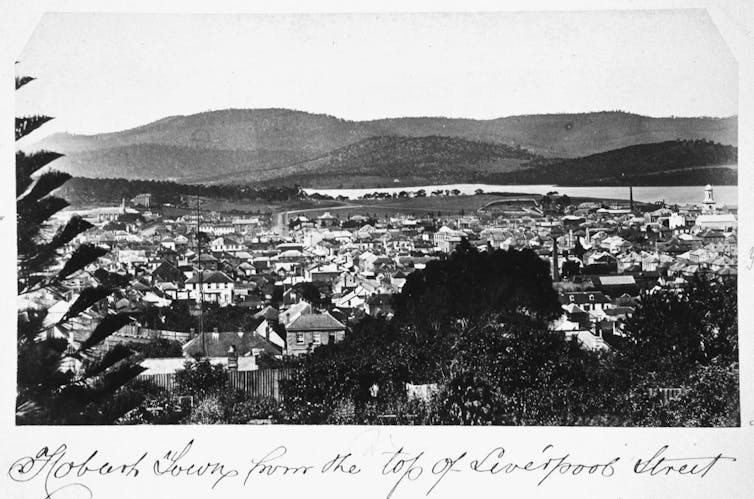

One fascinating locale is the Huon Valley – remote, utterly primitive, living from the forest and its timber, and a place to hide for those with secrets and nasty habits.

As each child is followed into indentured service and beyond, we glimpse the desperate poverty, the cultural isolation, the emotional wounds and the burdens of shame that blocked so many of the children and grandchildren of those who arrived “bonded” from taking their place in the Australian mainstream.

But the stories of determined survival were of both the children and their masters and mistresses, themselves often former convicts.

In the Huon Valley, James McDonald was apprenticed to a Mrs Catherine Halton as a gardener. Mrs Halton was a survivor: transported from Edinburgh on the testimony of her own mother who had left her without means to care for her younger siblings, while mother and her paramour cooled off in gaol. Catherine had pawned their clothes and paid the rent. She was an angry prisoner and much punished.

By 1875, she was a deserted wife and mother on a tiny farm on the Huon. James finished his indentures with her, so we can assume she fed and did not abuse him.

Read more: Hidden women of history: how 'lady swindler' Alexandrina Askew triumphed over the convict stain

Fortified and trained

Australian historians tend to underplay the back story of colonisation and its institutions. This is particularly so when it comes to social welfare or charity for those without families or the means to be self-sufficient. It was the late Patricia Crawford, a professor at the University of Western Australia and a distinguished historian of early modern England, who first pointed to the continuities between the English Poor Laws and colonial welfare institutions, in particular for First Nations people.

Crawford called it “civic fatherhood”, where the state (the civil parish or the colonial government) took upon itself the responsibilities to protect and educate those without capable parents by indenturing them as apprentices.

This was not reserved for orphans and bastards: all children, apart from those of “gentle birth” were traditionally expected to leave home at 12 and take up residence as an indentured apprentice for future training.

There were cruelties – and Frost opens her book with a brilliant narrative of a scandal at the Queen’s Orphanage where the rations were stolen for sale and children cruelly treated by the Matron, Harriet Smyth. But sadism and abuse have never been eradicated in care homes.

We get glimpses of a better life in the orphanage with brief references to the children’s band – music was often a major part of the care of the blind, for instance, as was handwork such as basket weaving.

Children had to be fortified and trained so they could avoid a life on the streets as beggars, or street sellers, or prostitutes. The prospects for orphan girls were dire unless they quickly found a decent husband or were enfolded in a caring household. (One suspects that being an attractive child or winning baby mattered.)

Lucy Frost is a great researcher, but she has short-changed herself in this book by excluding references or an index. There will be frustrated readers who would like to dig deeper, and many would be enthralled by the story of her finds. Her general account in the opening chapter is tantalising.

As researchers burrow away at court records, more and more ex-convicts are being found: in and out of gaol, hospital and institutions. Half crazy, angry, and alone except for their drinking mates. For all the success stories, the failures who could not put a stable life together after doing their time are legion.

Too many fell victim to the demon drink – and the start of their painful life journey through poverty, hunger, violence, alcohol and gaol goes back to their childhoods.

For we now know that what distinguished our convicts as a population, was that most came from fractured families in the first place. Dickens was not exaggerating.

Janet McCalman AC does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.