Something extraordinary has been happening for Australians seeking jobs in the past few months.

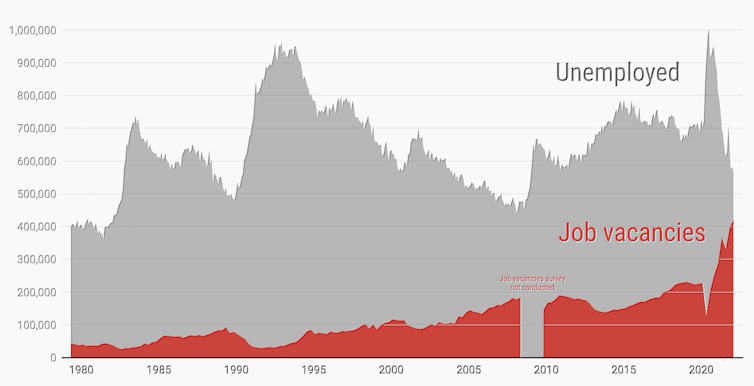

The number of vacant jobs on offer has soared to a new all-time high.

Figures released in budget week show there were almost twice as many jobs available in February this year – 423,500 – as in February 2020, before COVID arrived on our shores. And the number of Australians satisfying the ABS that they were “unemployed” was just 563,300, the lowest in 13 years.

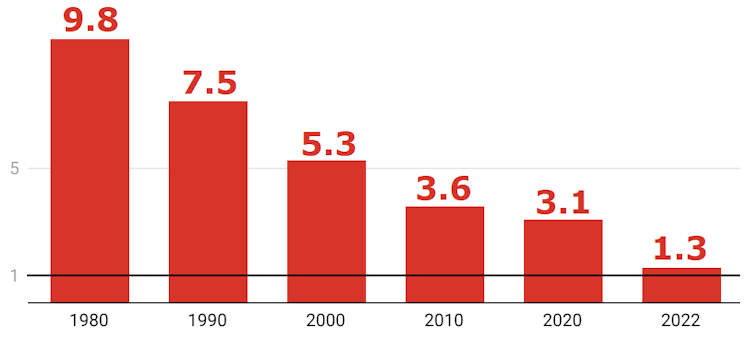

More job vacancies for each unemployed person than ever before

What this means is that in February 2022 there were only 1.3 unemployed people chasing each vacant job, the smallest ratio on record — down from three unemployed people for each vacancy in 2020, five for each vacancy in 2000, and seven in 1990.

Number of unemployed people for each vacancy

The unemployment rate is now just 4%, and is budgeted to fall to 3.75% within months, taking it to a five-decade low.

Our wages aren’t keeping up

Yet wages growth in Australia remains astoundingly low. Now 2.3%, it has been below 2.5% for seven years.

The Reserve Bank says it is targeting wages growth of “three point something”. It has failed to achieve it for the best part of a decade.

The low wage growth, compared with unusually high price growth, means wages growth has slipped 1.2% below price growth over the past year. That means what Australians are earning isn’t keeping up with rising prices.

Budget forecasts that don’t make sense

The budget anticipates price growth of 4.25% in 2021-22 alongside wages growth of 2.75%, meaning Australians’ buying power will shrink even more, by 1.5%.

In the Budget year, 2022-23, it predicts an uptick in wages growth to 3.25% alongside a dip in price growth to 3%, meaning wages would claw back 0.25% of the buying power they lost.

Read more: Why there's no magic jobless rate to increase Australians' wages

And here’s where this year’s budget forecasts don’t make sense.

It forecasts that what we’re seeing right now – price rises outstripping wages growth – is suddenly going to flip: that we’re about to see a slowdown in price inflation, alongside an acceleration in wages growth.

Here’s the odd part of it. On one hand, the Treasury is telling us it expects the unemployment rate to fall further below the “non-accelerating-inflation rate of unemployment” – which by definition means inflation would accelerate. Yet the budget predicts inflation will fall.

It’s a strange and unexplained departure from conventional forecasting.

Employers get to pick what they pay

If price growth merely stays at its current level of 3.5%, the budget’s forecast of 3.25% wages growth means real wages will fall.

And, given most of the budgets since 2014 have overestimated wages growth, it is worth considering what would happen if wages growth has been overestimated once again: real wages would fall still further.

Something weird is happening in the labour market.

With very few unemployed people available for each vacancy, employers ought to be offering higher wages to compete for workers.

But the concept of “monopsony” gives us an idea why that’s not happening.

The core idea of monopsony is that employers can choose (within constraints) the wages they pay their workers.

Read more: 'Can-do capitalism' is delivering less than it did. Here are 3 reasons why

If this sounds obvious, I apologise, but it’s very different to the perfect competition model of the labour market once loved by economists, in which wages are set by bargaining in a two-sided market.

When employers offer low wages, they can pay the price with higher staff turnover, unfilled vacancies, absenteeism or poor product quality.

But they still feel they can get away with paying low wages, and leaving many vacancies unfilled. And other employers feel they are forced to keep wages low, due to competing against low-price firms and because their immediate customers (such as supermarkets) insist on low prices.

These employers are able to choose to pay lower wages than in the past because workers are less powerful and their collective bargaining power is less effective than it once was.

Power imbalances keep wages in check

Work is insecure. Many workers face casual employment, contracting, labour hire, franchising or underemployment. Trade union membership has plummeted.

Only 12.7% of male workers are in a trade union in their main job, down from more than 50% at the start of the 1980s. Just 15.9% of women are, down from 43%.

Industrial disputes are at record lows partly because industrial laws have changed, making it extremely difficult for unions to strike for higher wages, and easy for employers to get around them.

Don’t expect any surges in real wages, no matter how tight the labour market is, while this new structure remains.

David Peetz receives funding from the Australian Research Council and, as an academic, has undertaken research over many years with occasional financial support from governments in Australia and overseas from both sides of politics, employers and unions.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.