The Chicago Police Department is warning officers to be on the lookout for members of a violent Venezuelan prison gang they say might be living among the 20,000 migrants who’ve come to the city over the past year.

But there’s little publicly available evidence that the gang, El Tren de Aragua, has a presence in Chicago. The gang is known in South America for human trafficking, drug sales, kidnapping and the violence that comes with it all.

A Chicago Sun-Times analysis, based on news reports, crime data and court records, identified more than 30 migrants from Venezuela who’ve been arrested in Chicago and DuPage County since April.

More than half of the cases involved theft and shoplifting. Two involved violent crimes — a robbery and a stabbing. Records show that only one of those migrants, charged with domestic battery, is listed in Chicago police records as being a suspected member of the prison gang.

Stores such as Macy’s and Nordstrom have been repeat targets of retail theft by Venezuelan migrant suspects in Chicago and Oak Brook, according to police.

One of them was accused of having hit two stores in four days. On May 4, the 34-year-old man was arrested and charged with stealing a watch, cologne and jewelry worth a total of $329 at the Nordstrom at 55 E. Grand Ave., but the case was dismissed. On May 8, he was arrested under a different name on a charge of stealing $720 of sportswear from the Macy’s at 111 N. State St. That case is pending.

The same man was arrested April 27 after punching another man in the face at a shelter in an argument over his turning on the lights too early in a communal sleeping area, according to police. That case got dismissed, too.

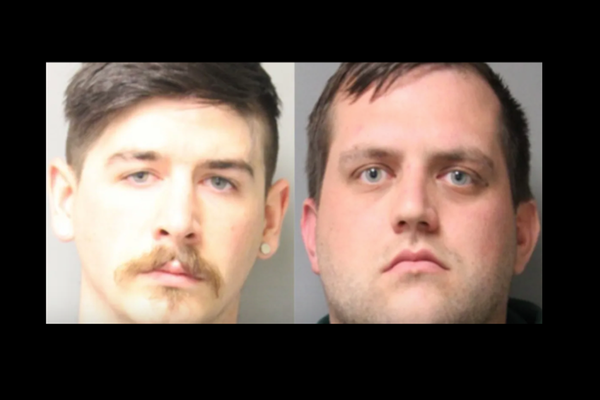

In DuPage County, two Venezuelan migrants living in Chicago were arrested on felony shoplifting charges at the Macy’s at Oak Brook Center on Oct. 23. Two others were arrested for the same charges a week later at the same store.

Of the cases the Sun-Times reviewed, the most serious involved a Venezuelan migrant, Jorge Goyo, 23, who was charged with stabbing a fellow asylum-seeker in August in the bathroom at the Grand Crossing police station, where Goyo was living. He’s free while awaiting trial for aggravated battery.

Another Venezuelan migrant was accused of pulling a knife on a Far South Side man and demanding his belongings in September outside the Standard Club at 320 S. Plymouth Ct. The suspect was living at the club, which has been converted into a migrant shelter. The case was dismissed.

Officials with the Chicago Police Department and DuPage County state’s attorney’s office declined to discuss crimes attributed to Venezuelan migrants.

“The sheriff’s office is aware of this organization and is working closely with local, state and federal law enforcement partners to monitor and address any potential threats to public safety or other criminal activity by suspected members of the gang,” said Matthew Walberg, a spokesperson for Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart.

The Chicago police and the sheriff’s office have put out internal alerts to officers about the possibility of members of the violent El Tren de Aragua prison gang living among migrants. Officials wouldn’t discuss those alerts.

In late October, a Venezuelan man — arrested on a charge of beating up his girlfriend in one of the migrant tents outside the Near West police district station at 1412 S. Blue Island Ave. — had tattoos that resembled those worn by the gang, according to a Chicago police alert.

The gang’s tattoos include a skull with a gas mask and an AK-47 rifle, according to the alert, which said that its members wear Michael Jordan No. 23 jerseys because the gang’s anniversary is Jan. 23.

A separate Cook County sheriff’s alert said investigators have learned that members of the prison gang are in the Chicago area.

Kyle Williamson, former head of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration office in El Paso, Texas, calls the gang “a huge criminal threat.”

“They are coming in” across the border, says Williamson, who runs the West Texas Anti-Gang Center. “We are seeing them.”

But Williamson says he doesn’t know whether the gang has a presence in Chicago. “I think we are a while away from seeing their true impact,” he says. “It takes time to get organized.”

The United States’ poor diplomatic relationship with the Venezuelan government makes it nearly impossible for U.S. law enforcement officials to get warnings about members of such gangs, Williamson says.

He says many young Venezuelan members of El Tren de Aragua lean against getting the gang’s tattoos because they don’t want to be recognized as members. He also says a crown is not a symbol of the gang, as the Chicago police alert suggested.

CNN reported Thursday that the U.S. Border Patrol says it has detained “38 possible members of the Aragua Train throughout six sectors, between October 2022 and the same month of 2023.”

In August, a man wanted in Venezuela on charges of financing terrorism was arrested after agents in the Justice Department’s Enforcement and Removal Operations learned he was in what they described as the “Chicago area of responsibility.”

The man “remains in federal custody pending immigration proceedings,” according to a spokesperson for the agency, who says she can’t provide details because of privacy restrictions.

Law enforcement sources say they’re concerned that laws designating Chicago and Illinois as places that provide “sanctuary” for migrants prevent them from tracking those who are arrested by their country of origin. They say it would be helpful to know how many people living in shelters and at police stations have been arrested in the Chicago area.

Experts say most of the Venezuelan immigrants who’ve landed in Chicago were fleeing rising crime and the imploding economy in their home country, arriving broke after being bused or flown from Texas.

The exodus to Chicago began last year with Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, saying he was sending asylum-seekers to Democrat-run sanctuary cities in the North, including Chicago and New York, so those cities would share the financial pain of dealing with the migrant crisis.

Civil rights advocates say there’s no evidence the migrants pose a particular threat to public safety. And they say the restrictions on looking them up by their immigration status are a good thing.

“When you think about the abysmal record that CPD has had with databases and gathering information on people, it’s confounding that cops would complain about their inability to collect information on migrants — especially legal asylum seekers,” says Ed Yohnka, spokesperson for the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois. “Singling out people because of who they are is not a step in that direction.”

Regarding migrants who have been charged with crimes such as shoplifting, Yohnka says he’s not surprised: “These are people who came here to work and take care of their families. Desperation drives people to do things that sometimes they shouldn’t do.”