This year marks 30 years since the artist, filmmaker and gay activist Derek Jarman died, aged just 52, in London in 1994. He had been diagnosed with Aids in December 1986, a decade before radical antiretroviral treatment lifted life expectancy of those diagnosed with HIV up to a more general, expected level.

In the same year, Jarman acquired a second home away from London, a fisherman’s cottage on the Kent coast. No doubt attracted to its situation in the dystopian cast of Dungeness nuclear power station, he had spotted it on a location visit with his friend and regular collaborator, the actor Tilda Swinton.

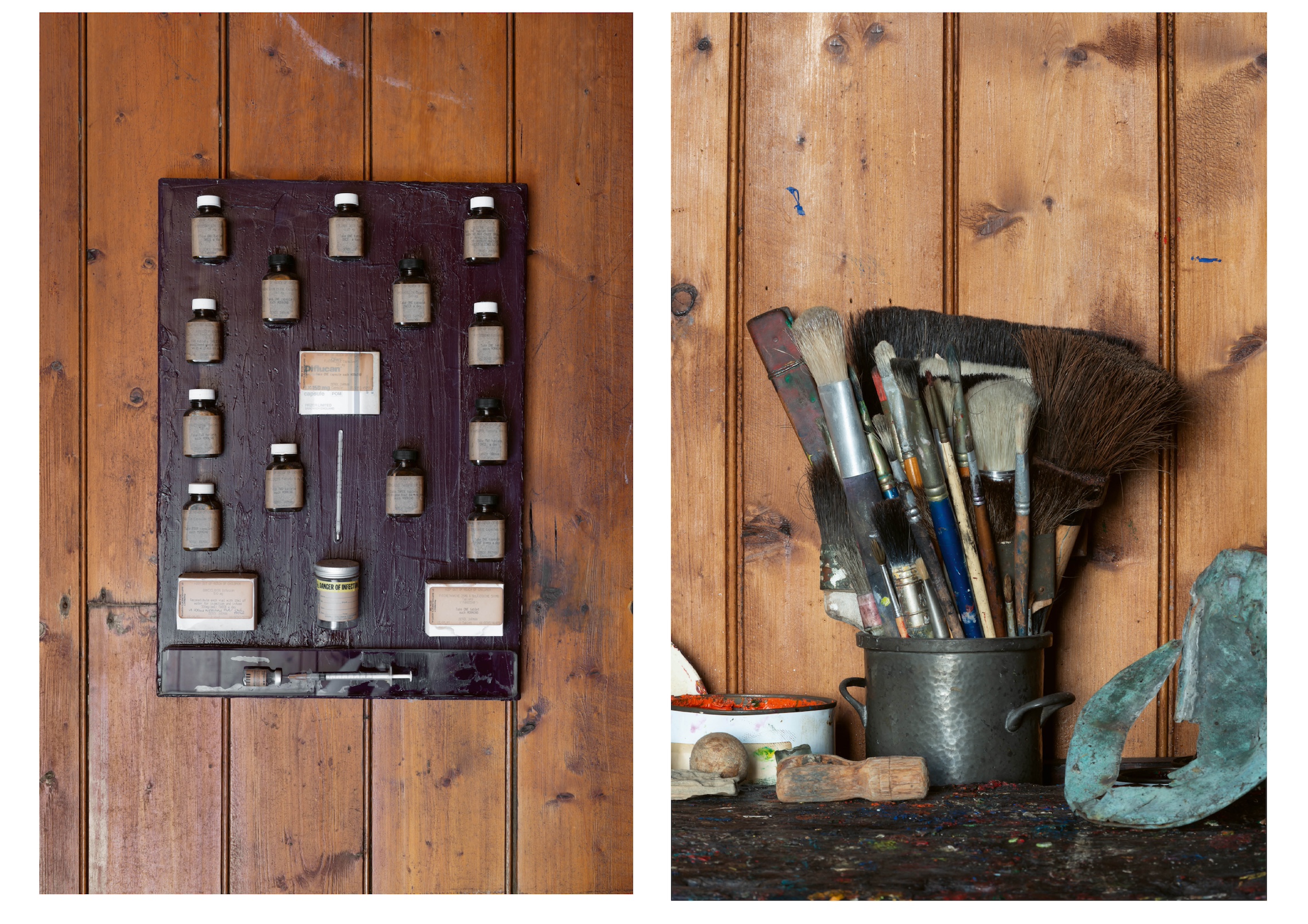

Next week, a new book, Prospect Cottage: Derek Jarman’s House, by Gilbert McCarragher, a Dungeness local, friend and photographer, invites us to experience the world as Jarman saw it from within the house, and of which he wrote in his diary, in 1990:

‘Prospect Cottage is the last of a long line of “escape houses” I started building as a child at the end of the garden: grass houses of fragrant mowings that slowly turned brown and sour; sandcastles; a turf hut, hardly big enough to turn around in; another of scrap metal and twigs, marooned on ice-flooded fields – stomping across brittle ice.’

Today, Prospect Cottage is a pilgrimage site, because while many of us who came of age in the 1980s will be familiar with the scope of Jarman’s art, arguably it is the house and his enchanting shingle garden that stirs the artist and activist's global reputation.

The garden, fenceless, reaching out into the shingle beach, is a generous legacy, but it is only recently that visitors have been allowed to enter the cottage, at certain times of the year. Otherwise, McCarragher’s book bestows as intimate a view of Prospect Cottage as you are likely to get.

Jarman and his partner Keith Collins lived between Dungeness and London for nearly a decade, and Collins was there alone for a couple of years after the artist’s death. It was he who hung net curtains up to prevent a constant stream of curious visitors peering inside. Now, they are gone and, after a dedicated, nationwide campaign, Prospect Cottage is saved for the nation and under the careful management of the Creative Folkestone arts organisation.

This new book, and McGarragher’s devotion to both the house and its subjects offer touching insight to Jarman as a person, beyond his significant cultural and political achievements. Art historian Frances Borzello’s moving foreword also illuminates Jarman’s deeply poetic nature, allowing us to understand, in some way, the gnawing void that those closest to him are destined to live with every day.

The book, then, while a highly readable addition to our understanding of this towering cultural figure as a human being, feels nowhere near epic enough and begs for a weighty tome with expansive page sizes and filmic crops. But then, perhaps that’s besides the point.

Prospect Cottage: Derek Jarman’s House with photography and words by Gilbert McCarragher is published on 4 April 2024 by Thames & Hudson, £25