Spinosaurus is the biggest meat-eating dinosaur ever discovered, larger even than the famous T. rex. However, the way the ancient beast hunted its game has been debated for decades. Now new research suggests its dense bones enabled Spinosaurus to seek prey underwater.

Most groups of vertebrates on land have members that have returned to a life either partly or fully aquatic. Among mammals, there are whales, seals, otters, and hippos; among birds, penguins; among reptiles, alligators, crocodiles, marine iguanas, and sea snakes. However, for a long time, with the exception of birds, dinosaurs were largely thought an exception to this pattern, with only a few suggested to be partly or fully aquatic.

However, in 2014, evidence appeared that Spinosaurus could swim, with the giant sail on its back rising from the water like the dorsal fin of the great white shark. The first fossils of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus were actually discovered more than a century ago in the Egyptian Sahara. Unfortunately, all of them were destroyed in World War II during the 1944 Allied bombing of Munich, leaving much uncertain about this carnivore. New fossils unearthed in the Moroccan Sahara within the past two decades revealed Spinosaurus possessed a suite of previously unknown adaptations that may have allowed it to live much of its life in the water, such as conical teeth ideal for catching fish, paddle-like feet, a fin-like tail, and small nostrils in the middle of its snout to help it breathe even when its head was partially submerged.

Still, much remained debated about how Spinosaurus actually lived — whether it swam after prey, or just waded in the water like a heron.

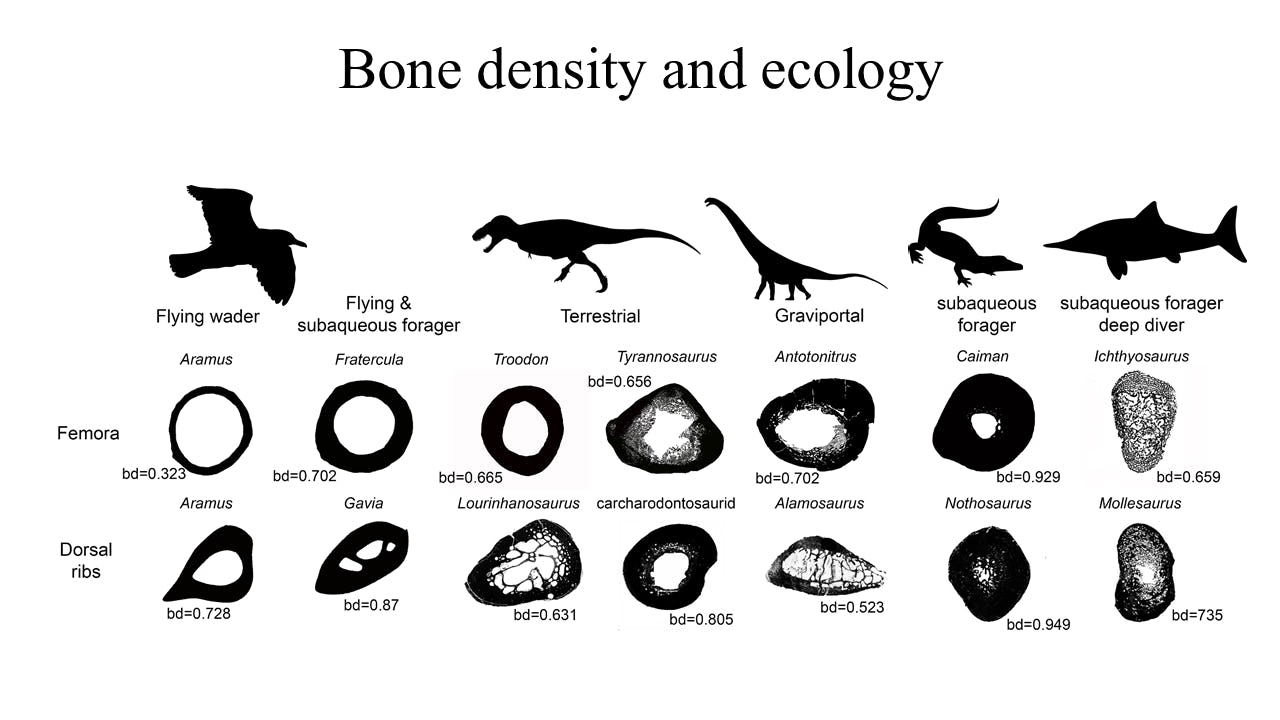

What the new study found — Prior work suggested bone density might serve as a marker of how often an animal might spend time sinking into water, much as an anchor can help keep a boat in place. To find support for this idea, researchers examined 250 species of extinct and living animals, both land-dwellers and water-dwellers.

By analyzing 380 rib and thigh bones from everything from mice to elephants and hummingbirds to whales, as well as extinct marine reptiles such as plesiosaurs and mosasaurs, the scientists aimed to discover if dense bones were linked to aquatic species. This in turn could help them learn more about extinct creatures with mysterious lifestyles, such as Spinosaurus, by looking at their fossils.

The scientists detailed their findings online on March 23rd in the journal Nature.

The scientists discovered a clear link between dense bones and aquatic foraging. Animals that submerged themselves in water to find a meal possessed bones that are incredibly dense, nearly completely solid throughout, whereas cross-sections of land-dwellers' bones looked more like donuts, with hollow centers.

These findings revealed that Spinosaurus and its close relative Baryonyx had dense bones that likely would have helped them sink underwater to hunt. On the other hand, another related dinosaur known as Suchomimus had lighter bones that would have made swimming more difficult. It likely still lived by the water and dined on fish, given evidence such as its crocodile-like snout and conical teeth, but it probably waded like a heron or spent more time on land like other dinosaurs. Such adaptations likely appeared in this group, known as spinosaurs, roughly 100 million to 145 million years ago, when it diverged from other large carnivorous dinosaurs.

"We were very excited and surprised to see different ecological adaptations among spinosaurs," study lead author Matteo Fabbri, a paleontologist at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, tells Inverse. "We are probably underestimating the ecological diversity of extinct animals."

Other dinosaurs, such as giant long-necked, long-tailed sauropods such as Brontosaurus, also had dense bones, but the researchers did not suggest these also swam. Heavy animals such as elephants and rhinos may possess dense bones to support their weights, but their other bones are typically lightweight, Fabbri says.

This "excellent study" demonstrates "that bone microstructure can be a Rosetta Stone for interpreting the ecology of ancient animals, particularly lifestyles tied to the water," vertebrate paleontologist Lindsay Zanno at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, who did not participate in this study, tells Inverse.

What’s next? — These findings help show what paleontologists can deduce about an extinct creature's lifestyle even from a few fossils, Fabbri notes. Research such as this work that draws on hundreds of specimens may prove time-consuming, but ultimately can help reveal big patterns in biology, study co-author Jingmai O'Connor, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Field Museum, noted in an accompanying press release.

Future research can examine other spinosaurids and groups of dinosaurs. In addition, investigating other extinct reptiles and mammals may reveal "surprising ecological adaptations that we are still ignoring," Fabbri says. "Our study is more a starting point, rather than a final word."