History is full of examples of governments using forced segregation against ethnic minorities.

From settler colonialists coercing Indigenous peoples into reservations, Nazis forcing Jews into ghettos or the United States segregating Black Americans through redlining and zoning policies, displacement and housing have long been at the heart of institutional racism.

But in today’s Europe, an inverted trend of coercive assimilation is emerging in northern nations grappling with high levels of immigration. As a part of what has been described as both “ethnic engineering” and among the “harshest immigration policies” in the world, Denmark is forcibly uprooting people from neighborhoods they call “ghettos” and redirecting them to alternative housing.

In neighboring Sweden, politicians have expressed a desire to pursue similar plans.

The uprooting of whole communities is controversial. This winter, Europe’s highest court, the European Court of Justice, is set to determine whether Denmark is violating the civil and human rights of those being rehoused. As an expert in displacement and immigrant incorporation, I believe that the court’s decision and the progression of Denmark’s program have great implications for the future of Europe’s immigrants and the true meaning of European citizenship for its people of color.

Denmark’s ‘ghetto package’

Denmark’s radical housing policy is years in the making. In 2010, the country’s authorities began compiling lists of “non-Western,” immigrant-majority neighborhoods that were failing to live up to set standards on lawfulness, employment, income and education levels. Areas that fell short in two of the four of these criteria were officially labeled “ghettos,” or “tough ghettos” if they fell short of more than two criteria.

While these neighborhoods are home to people with a diverse range of ethnic backgrounds, they are marked by having more than half of residents with backgrounds in non-Western nations, including Syria, Iraq and Somalia.

Areas with “Western” majorities that failed the same standards were labeled “vulnerable areas” in contrast to the “non-Western” ghettos.

In 2018, the social democratic Danish government launched the “Ghetto Package,” a legislative program aimed at breaking up the “ghetto” neighborhoods – and the social fabrics that sustain them. The package did not entail the same measures for “vulnerable areas.”

Proposals to this end consisted of reducing public housing to no more than 40% of total housing in the neighborhoods and measures to encourage white, wealthier residents to move in.

As a result of the initiative, thousands of people have been displaced and removed from their family homes through sales, demolitions and forced evictions. Some of the homes were renovated while awaiting new tenants, while others were sold to private investors who planned on raising rents by more than 50%. Evicted residents are typically offered alternative accommodation in public housing in other parts of the city or region, but with no control over location or cost.

Denmark’s assimilation program does not stop at the breaking up of low-income, predominantly immigrant neighborhoods. Children born into “non-Western” families in state-designated ghettos must attend special programs for a minimum of 25 hours per week beginning at the age of 1, designed to immerse them in “Danish values,” including Christian holidays and Danish language education. Parents are not allowed to accompany them.

In addition, the program also wants to turn “ghettos” into “harsh penalty zones” in which crimes can be penalized twice as severely.

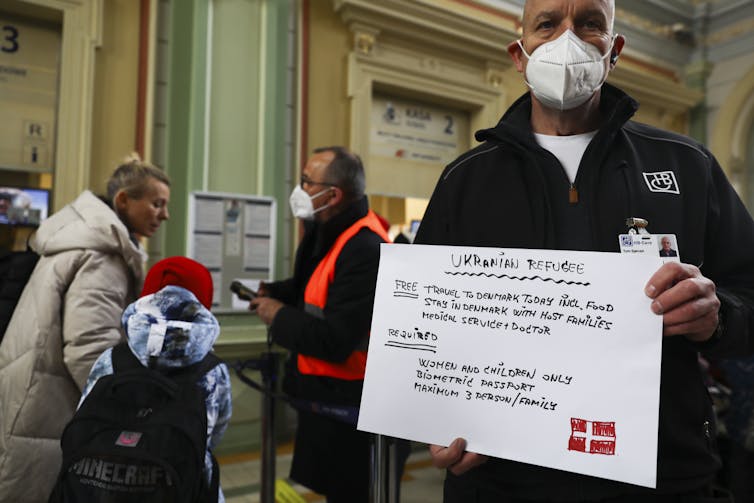

Residents and other critics of the package of measures argue that the designation of “non-Western” in practice means “nonwhite” or “Muslim,” pointing out the fact that non-Europeans such as Australians and New Zealanders are excluded from the criteria, and that Ukrainian refugees fleeing the Russian invasion in 2022 were permitted to move into social housing that “non-Westerners” had been forced to leave.

Moreover, being a naturalized Danish citizen or Danish-born does not count as being Western for people of color; nonwhite, second-generation immigrants are formally considered non-Western under the program, implying a race-based criteria of belonging.

In response to the law, a dozen residents facing eviction from Mjølnerparken, a residential area categorized as a “tough ghetto” in Copenhagen, filed a case against Denmark’s Ministry of Social Affairs in 2020. In September 2024, the European Court of Justice held an initial hearing to determine whether the government’s Ghetto Package is discriminatory under Danish law, European Union law and the European Convention on Human Rights. Deliberations are underway.

Pending a verdict, the United Nations has urged Denmark to suspend the sale of homes in affected areas, but to no avail.

Ghettos, ethnic enclaves and parallel societies

Immigrants congregating in the same residential neighborhoods is nothing new.

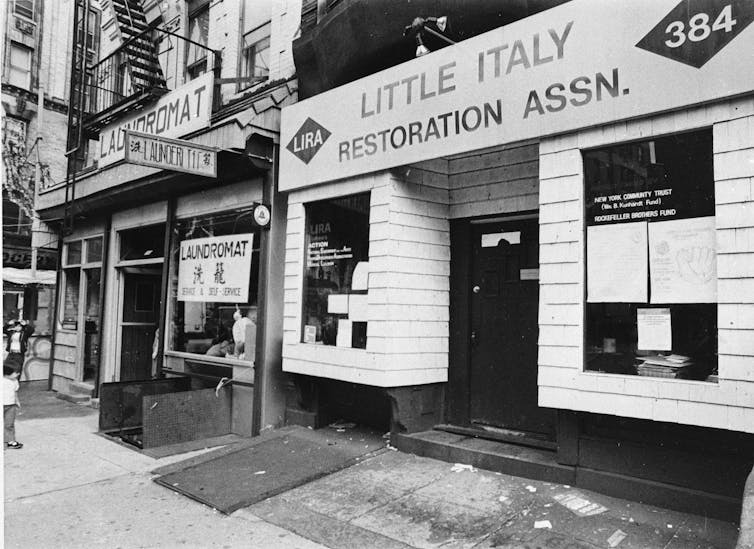

In American social science, the term “ethnic enclave” is a relatively neutral concept that refers to a community dominated by a certain ethnic group or population. Prominent examples include Little Havana in Miami, Chinatowns in New York and San Francisco, or Boston and New York’s Little Italy.

Historically, these communities formed their own social support systems, networks and economies in lieu of government support and have become important cultural centers.

But amid high levels of immigration in recent years, many European countries have become less accepting of the idea of immigrant-majority neighborhoods.

In those cases, integration is increasingly being seen as the cornerstone of sustainable immigration policy, even as state policies can be drivers of segregation between ethnic Europeans and immigrant communities.

Indeed, accusations of failed integration are a common political response to rising rates in crime and gang violence in Scandinavia, and Europe more broadly, and are the reasons cited for more restrictive immigration policy. Built into this notion is the assumption that immigrants of non-Western backgrounds are a bad influence on each other – and, in turn, on Europe.

In many European countries, the term “parallel societies” has cropped up. It is used to signal a development in which immigrant communities – predominately Muslim or from the Middle East and North Africa – are deemed not just a threat to local European culture and values but also to public safety.

To some politicians – initially just those on the right, but increasingly in political mainstreams – parallel societies such as those on Denmark’s list are potential breeding grounds for antidemocratic values, delinquency and violence.

Targeting the community

Proponents of Denmark’s current immigrant policy say they want to avoid the rise of gang violence seen in some areas of Sweden and promote a more integrated society.

But opponents of the “ghetto” policy say there is little evidence linking the culture of immigrant communities to problems of public safety. Instead, they point to the seductive techniques of predatory gangs, often online and with leadership based abroad, that target the young, disillusioned or impressionable.

Others say Denmark’s program is an excuse for gentrifying up-and-coming urban areas. Mjølnerparken is part of Nørrebro, selected “the world’s coolest neighborhood” by Time Out for 2021, thanks to its multiculturalism and vibrancy.

While the “Ghetto package” claims to promote integration, it risks alienation. For immigrant communities and critics of the current policy in Denmark, the program raises the question of who is considered part of a national community and identity and who is considered an inherent outsider or threat to it.

“I felt Danish until recently,” an immigrant Danish resident told Al Jazeera in 2020. “The politicians created their ‘parallel society,’ with the bad reputation they’ve given Mjølnerparken so that ethnic Danes don’t want to live here.”

It is a feeling increasingly shared by immigrant groups across the continent. In recent years, European leaders have proposed and implemented anti-immigrant policies that would have been inconceivable in many political mainstreams just a few years ago – even as border crossings into Europe have decreased dramatically.

The Danish experience shows that this new wave of radical anti-immigrant sentiment is not targeting just incoming migrants but settled ones as well.

Selma Hedlund does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.