I once accompanied Denis Healey canvassing for votes in Wales in support of a Labour candidate fighting a byelection campaign. It was a joy. As chancellor, he had presided over some extremely bleak economic times for the country, and he had retired from the front rank by now, but the response on the street was universally warm.

Had the selfie existed then, people would have been queuing up for them. For he was not just one of the most significant figures in postwar politics, he was a vibrant personality, a man who embraced challenges with relish, a man for whom the cliché “larger than life” might have been minted, and a man who didn’t let his high intelligence get in the way of enjoying the fun of the game.

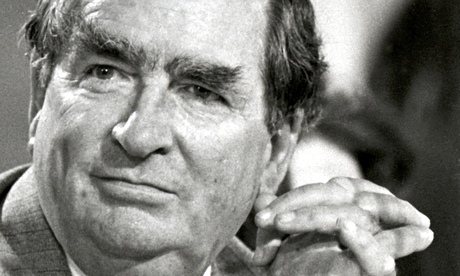

His famously bushy eyebrows danced with pleasure as he exchanged repartee in his deeply chuckling voice with passing voters. “Whose a silly-billy then?” some would say, repeating back to him his catchphrase. It had actually been coined by the impressionist Mike Yarwood, but Denis had adopted it as his own.

He was one of the exemplars of a special generation of Labour politicians: big people, tough people, brave people, complex people, men forged in war and ambitious to build a better country in the peace. From a humble ancestry, he went to Bradford Grammar School and then achieved an exhibition to Oxford where he secured a double first in greats.

During the struggle against Nazism, he had what people called “a good war”. He served with the Royal Engineers in north Africa and was subsequently a beach officer at the Anzio landings, one of the toughest engagements of the campaign in Italy. He wore his major’s uniform when he addressed the Labour party at its triumphant 1945 conference. By 1952, he was in the Commons as MP for Leeds East and became a consistent champion of the moderate wing of the party during the splits of the 1950s and thereafter.

Strongly of the Atlanticist tradition, he was defence secretary throughout the Wilson governments of 1964-70. He presided over the postwar accommodation to the country’s reduced means in the world and kept Britain out of the Vietnam war. One of his most controversial acts was to authorise the expulsion of the population of the Chagos Archipelago and the building of a US base at Diego Garcia.

When Labour returned to power in 1974, he became chancellor and inherited an exceptionally poisoned chalice from the outgoing Heath government. The multiplying of oil prices was crippling the economy. The miners’ strike had put the country on a three-day week. Inflation was out of control. His entire tenure was punctuated by a series of hideous financial and political emergencies, the most severe of which was when Healey was forced to seek a bailout from the International Monetary Fund. He had to break away from the IMF negotiations to dash to the party conference in Blackpool to try to convince a rebellious party that it had to accept cuts to public spending to secure the IMF deal. That he did with a brave speech, much of it delivered at the level of a shout to make himself heard over a bombardment of booing and heckling by the dissenters.

Given the severity of the economic situation, and that Labour had no majority in the Commons, it was almost a miracle that the government managed to endure for more than four years. Healey deserves a lot of the credit for its survival. By the end of his tenure, inflation had been curbed, if not fully controlled. The economy was growing. Unemployment was falling. But he and his close ally at No 10, Jim Callaghan made a serious strategic error by not calling an election during a break in the weather in the autumn of 1978. Major trade unions revolted against their “pay norm”, the government-imposed cap on wage increases. The result was the disastrous winter of discontent, defeat at the hands of Mrs Thatcher the following May, and 18 years of Tory government.

With Labour now back in opposition, disillusion within the party’s ranks ignited the leftwing revolt led by Tony Benn. That battle came to a climax when Benn contested Healey for the party’s deputy leadership. Healey’s victory – “by an eyebrow”, as he once joked – was a crucial point in turning back the Bennite tide. It was not enough to prevent Roy Jenkins leading a breakaway of Labour moderates to form the SDP. Though he shared their views about Europe and the nuclear deterrent, Healey had only contempt for the defectors: in his view, you stood and fought your ground, you did not run elsewhere.

He retired from the frontbench after the 1987 defeat and from the Commons in 1992, but continued to offer opinions about politics in a style uniquely his own. Phone calls to his home in East Sussex would often be rewarded with Healey putting on a Chinese accent and pretending to be the cleaner.

He had a wit that was caustic and an inventive turn of phrase. That made him some enemies among his victims, but it won more admirers.

During the vicious battles with the Bennite left, he told one of their number that he was “out of his tiny Chinese mind”. He dubbed Margaret Thatcher “Attila the Hen”. His description of doing parliamentary battle with his Tory opposite number Sir Geoffrey Howe – “like being savaged by a dead sheep” – instantly won a place in collections of great political quotations. At the same time, he and Howe developed a warm relationship which continued long after they had both retired from the frontline. For Healey was never the blind tribalist in his politics and ever conscious that opponents were people too.

He had a humanity that made him attractive in a profession not always noted for it. He had a hinterland. Indeed his friends sometimes wondered whether he had too much interest in life beyond politics and that had denied him the premiership. Photography was a passion. So was poetry. His autobiography – The Time of My Life – is one of the best-written of political memoirs. He had an exceptionally strong marriage to Edna. He once told an interviewer that he did not need the love of the people because he had the love of his wife.

He has often been included in might-have-been lists of “the best prime ministers we never had”. Today we should remember him as one of the great politicians we did have.