Denis Goldberg was a railway engineer who became one of the most prominent white anti-apartheid activists in South Africa, spending 22 years behind bars for plotting to overthrow the country’s brutal system of racial oppression.

Working alongside Nelson Mandela and other leaders of the African National Congress, Goldberg, who has died aged 87, was part of a multiracial coalition dedicated to overthrowing apartheid, the segregated system that propped up white minority rule in South Africa for nearly half a century. He went on to become a kind of elder statesman for the movement, calling on the ANC – modern South Africa’s ruling party – to recommit itself to social justice and economic equality amid a wave of recent corruption allegations.

A first-generation South African, Goldberg had been immersed in left-wing politics from childhood and faced discrimination as a young man for his Jewish ancestry and his parents’ communist views.

“I understood that what was happening in South Africa with its racism was like the racism of Nazi Germany in Europe that we were supposed to be fighting against,” he said in 2019. “You have to be involved one way or another.”

Beginning in the early 1950s, he engaged in a campaign of nonviolent resistance, joining the underground South African Communist Party and the Congress of Democrats, a white anti-apartheid organisation that partnered with groups including the ANC and the South African Indian Congress.

As a result of his efforts, he spent four months in prison in 1960 and was dismissed from his job at the state-owned railroad company. That same year, 69 demonstrators were gunned down by police in the township of Sharpeville – a massacre that spurred the creation of Umkhonto we Sizwe, or Spear of the Nation, an armed branch of the ANC that launched a wave of bombings and other attacks directed at government property, including railways and power lines.

Goldberg was an early member of MK, as the group became known, and applied his engineering expertise to the manufacture of homemade explosives before being arrested in a 1963 raid on the organisation’s hideout, at a farm in the Johannesburg suburb of Rivonia.

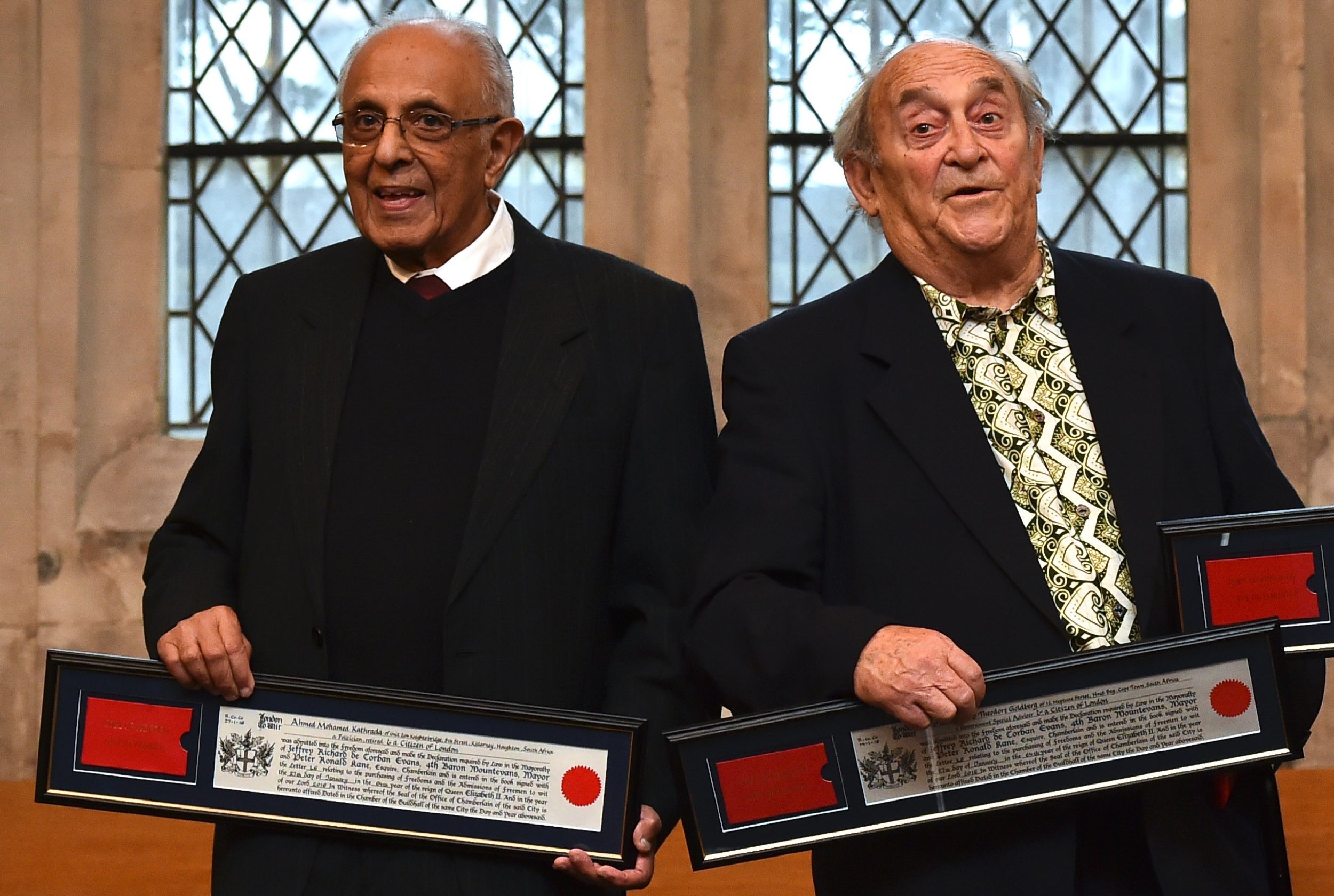

Charged with planning a “violent revolution” against the government, Goldberg was tortured in confinement and soon appeared in court alongside defendants including Ahmed Kathrada, Walter Sisulu and Mandela, who was already imprisoned on separate charges. The Rivonia trial riveted the nation, with Mandela delivering a courtroom speech in which he called for “a Democratic and free society in which all people will live together in harmony ... an ideal for which I am prepared to die”.

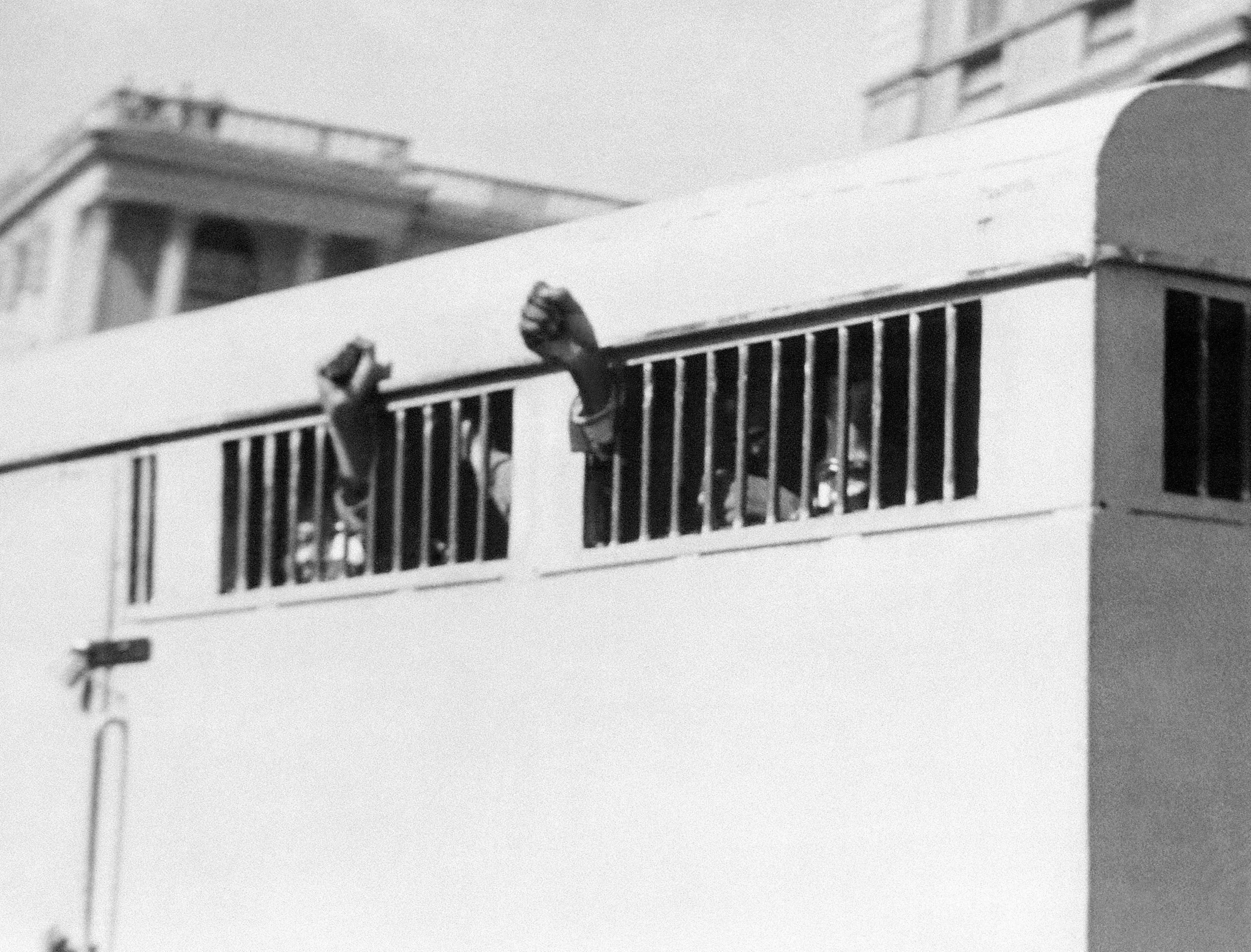

Instead of receiving death sentences, Mandela and seven others – including Goldberg, the youngest and only white man convicted – were sentenced to life in prison.

His time in prison left him more subdued. Goldberg was separated from his non-white comrades, who were imprisoned on Robben Island, an Alcatraz-like compound where they were forced to work at a limestone quarry. He was sent instead to a whites-only wing for political prisoners at a penitentiary in Pretoria, where he found himself isolated and increasingly depressed, with a nagging sense that he might die behind bars, even as apartheid seemed increasingly on the verge of collapse.

Goldberg was granted visitors intermittently and during one brutal stretch went 14 years without seeing his wife. Amid pressure from the Israeli government, he was released in 1985 on the condition that he give up armed resistance – an offer that was declined by Mandela, who remained in prison for another five years.

Speaking to reporters after his release, Goldberg said he had experienced a “deep yearning” to see his family again and felt emotionally weakened by his long absence from his comrades on Robben Island. “Twenty-two years ago,” he said, “I kissed my daughter and son good night and walked out of their lives ... Strength is a collective, not an individual thing.”

His parents had died and his two young children had grown into adults. But he had no regrets, saying he had worked as part of a struggle for equality so his children could “grow up without having to worry about these things”, and continued working as a nonviolent political activist.

After his release from prison, Goldberg worked as a spokesman for the ANC, oversaw South African charitable efforts and, in lieu of running for political office, advised a government minister for water affairs and forestry. He periodically made headlines for his criticisms of former president Jacob Zuma and other ANC leaders whom he accused of corruption and cronyism.

Denis Theodore Goldberg was born in Cape Town in 1933. Both parents were London natives, the children of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania. His father, a merchant seaman during the First World War, had an adventurous streak that led the family to settle in South Africa, where he ran a small bus company. His mother later spent time in prison for her anti-apartheid activism.

Goldberg studied civil engineering at the University of Cape Town, receiving a bachelor’s degree in 1955. He turned toward activism with encouragement from Esme Bodenstein, a physical therapist who treated him for a college rugby injury and was later held in solitary confinement for her anti-apartheid work.

They married in 1954, and while Goldberg was imprisoned in Pretoria she lived in exile in Britain, raising their children, David and Hilary Goldberg. She died in 2000, and two years later Goldberg married Edelgard Nkobi, a German journalist who died in 2006. His daughter died in 2002.

He is survived by his son.

Denis Goldberg, anti-apartheid activist, born 11 April 1933, died 29 April 2020

© Washington Post