Women have been running for president of the United States since 1872, and for almost that long people have been asking what women need to do in order to break what Hillary Clinton has called the “highest, hardest glass ceiling” left in American culture.

Almost no one has asked what men need to do in order to remedy the problem that the job has been off-limits to more than 50% of the talent pool since … forever.

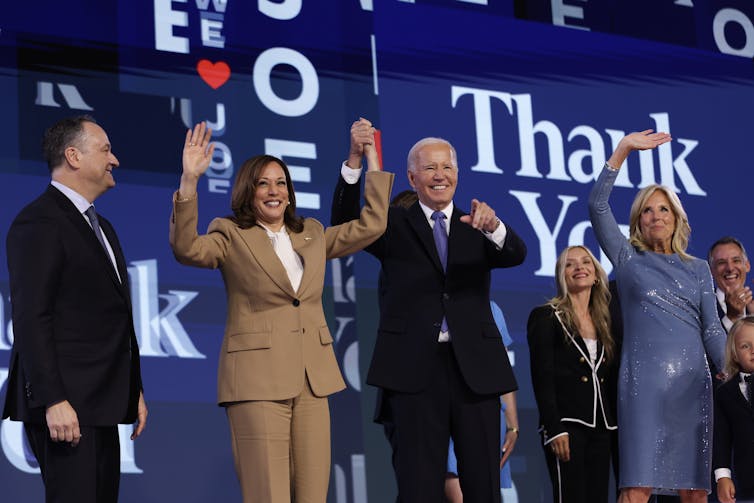

At the 2024 Democratic National Convention, that changed. Democratic men made choices that were entirely new, or exceedingly rare, in support of a woman presidential candidate and in service to the nation. It was unprecedented.

As a communication scholar who studies gender and political leadership, I’ve argued that the biggest impediment to electing a woman as president is not a dearth of qualified woman candidates but a collective inability to recognize them as such. The fault is not in the candidates but in American culture.

As it turns out, men in politics were also to blame.

When faced with competitive women as presidential candidates, many men historically have leveraged their power and privilege in ways that undercut women’s candidacies. But the Democratic convention was different.

For the first time in history, men in a major political party offered unified support for a woman candidate. They refrained from strategically deploying the stereotype that strong women are not likable, as Barack Obama did with Hillary Clinton in the 2008 Democratic primaries.

They accepted the party’s overwhelming support for a woman candidate, instead of insisting on being entitled to superdelegates, as Bernie Sanders did in 2016.

And they put their career on hold to support their spouse’s candidacy instead of undercutting it by offering support to primary campaign challengers, as Bob Dole did when Elizabeth Dole sought the Republican Party’s nomination in 2000.

‘Relinquishing male power’

Rhetorical choices reveal the underlying motivations of individuals and groups. The messaging of Democratic men at the 2024 convention signaled that their party was finally ready to do something that no major party has ever done. They were not only nominating a woman candidate but relinquishing male power and privilege.

Biden surprised everyone when he pulled out of the race in response to pressure from flagging poll results, skeptical donors and party leaders, and nervous down-ballot candidates. Any resentment he may have felt, however, did not turn into pique or pettiness at the convention.

When the crowd chanted, “Thank you, Joe,” he instructed, “Thank you, Kamala, too,” and promised to be “the best volunteer the Harris and Walz camp have ever seen.” He didn’t just give up his candidacy. He ceded his authority – to the people and the party, but also to Harris, specifically.

Although Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg angled to be Harris’ running mate and may still harbor his own presidential aspirations, he did not use his convention speaking slot to audition for the 2028 campaign. Instead, he performed the role that historically has been reserved for women at political conventions: pitching the party’s message via the perspective of a parent whose primary concern is “kitchen table” politics, issues that affect children and families most directly.

The convention speech given by the presidential nominee’s spouse has historically been an opportunity for prospective first ladies to portray their husbands as patriarchs of an ideal American family. In his speech, second gentleman Doug Emhoff painted a picture of a “complicated” and “blended family” with no patriarch but two active partners, equally capable of professional success and deep commitment to family.

When Harris selected Tim Walz as her running mate, she defied many pundits and the oddsmakers who deemed Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro the best strategic choice. Walz’s convention performance was described by one news outlet as the message of a “midwest ‘man’s man’” and the “antidote to toxic Maga masculinity.” Even Ms. magazine touted it as a “Masculinity-Themed Populist Pep Talk.”

But Walz did something Americans are not used to seeing “man’s men” do. He made it clear that he could work not just with, but for, a woman. And that everyone should.

After informing the crowd that the election was in the metaphorical “fourth quarter,” the team was “down a field goal” and the offense was “driving down the field,” Coach Walz made it clear that, as in his high school coaching days, he was the assistant coach. Their leader was Kamala Harris, and “Kamala Harris is tough. Kamala Harris is experienced. And Kamala Harris is ready.”

Contented second fiddles

To be clear, Harris’ early success as a presidential candidate should be attributed, first and foremost, to her skillful and dexterous response to a series of unprecedented events and to the savvy support of the Black women who have long sustained the Democratic Party.

But the men of the convention made a collective choice to embrace “their second-fiddle roles,” as an Axios reporter described it, and treat Harris like a commander in chief. That should be unremarkable. Women have been doing it for presidential candidates since … forever. But to see so many white men stepping back so enthusiastically for a woman of color was almost unbelievable.

Stepping back is not the same thing as stepping away. That’s important, because the broader message of the convention was about how to create an inclusive, democratic community. When you need to make a circle wider, and let more people in, you step back. That doesn’t leave you out of the circle. It makes your circle bigger.

The convention offered an expansive circle that includes gay dads raising strong-willed toddlers, blended families that attend synagogue and church, football coaches who bag pheasants and serve as faculty adviser to the high school’s gay-straight alliance club, and presidents who give up their power for the good of the country.

It also includes a presidential candidate who looks like no other president in U.S. history. That’s a big step forward for the country.

Karrin Vasby Anderson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.