Happy Tuesday and welcome to another edition of Rent Free. For the past couple of weeks, I've been trying to refocus the newsletter away from presidential politics and back on the state and local stuff that really matters. And for the past couple of weeks, they keep dragging me back in like Michael Corleone.

Our stories this week will have some local-level developments, including:

- Gainesville, Florida, famous for eliminating and then reimposing single-family-only zoning, has passed minimum lot size reform.

- Berkeley, California, the birthplace of single-family zoning, is considering allowing low-rise multifamily development everywhere.

- A federal judge has stopped Castle Rock, Colorado, from enforcing its zoning code against a local church that's been offering temporary shelter to the homeless.

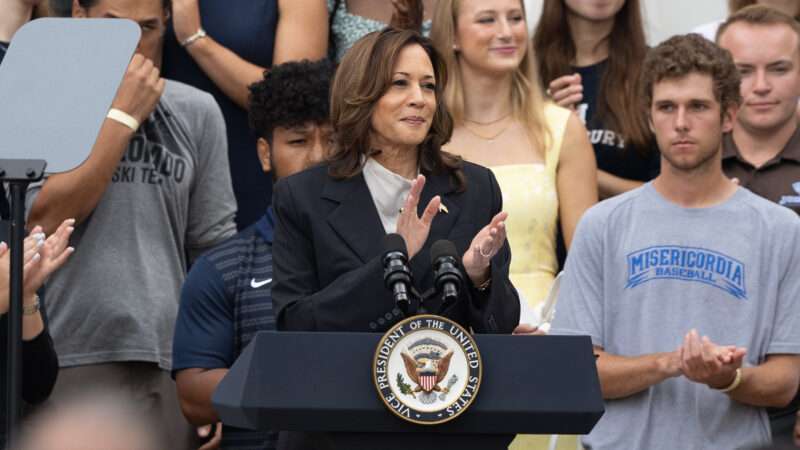

But, since we have a new presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, our lead story will look at the housing policy implications of a possible President Kamala Harris.

A Complicated Coconut Tree of Demand Subsidies and Price Controls

We can glean a pretty good understanding of what a Kamala Harris White House might do on housing policy because she's been in the White House for the past three-and-a-half years.

As President Joe Biden's vice president, Harris' housing policy record is effectively Biden's housing policy record. Which is to say, it's not great.

The Biden-Harris White House has certainly said all the right things about the need to remove regulatory barriers to new housing supply to bring housing costs down. Harris' name has appeared on many of its pro-supply statements.

However, the administration's efforts to incentivize state and local deregulation with federal grant programs have been a big flop thus far. It's also tightened federal fair housing and environmental regulations that likely drive up the costs of housing construction. Its fiscal agenda of tariffs and big spending increases has increased the costs of finance and materials needed to build homes too.

Harris' pre-vice-presidential housing record isn't much better. She left a pretty sparse housing policy record during her eight years as California's attorney general—an office that theoretically has a lot of power to force NIMBY local governments to plan for new housing.

In fairness, prior to current Attorney General Rob Bonta—and a suite of new YIMBY laws giving his office more power and direction—California attorney generals generally didn't do much of anything to crack down on NIMBY localities. Harris isn't remarkable for being absent on this issue. Her absence is nonetheless evidence that she's not been a leader on the issue either.

Harris did take a keener interest in housing policy as a senator and 2020 presidential candidate, although the policies she put forward tended to be overly complicated, Rube Goldberg-style contraptions that ignored removing supply barriers in favor of subsidizing demand.

Harris' campaign trail plan for closing the racial homeownership gap called for spending $100 billion on downpayment assistance for individuals who'd lived for the past ten years in a low-or-moderate income census tract, made less than $50,000 (or $75,000 in a high-cost area), and were purchasing a principal residence worth $300,000 or less.

That's a lot of moving parts for a policy that ultimately few people would qualify for and does nothing to address the most serious barrier to homeownership for people of all races: regulatory limits on the construction of new homes.

As a senator, Harris' main housing policy initiative was her Rent Relief Act—a bill that would have given people refundable tax credits to cover the rent they paid in excess of 30 percent of their income.

This benefit was means-tested: those earning up to $100,000 could get a tax credit worth 25 percent of the rent they paid in excess of 30 percent of their income, people making up to $75,000 could get a tax credit worth 25 percent of the rent they paid in excess of 30 percent of their income, and so on. People in subsidized government housing, where rents are capped at 30 percent of one's income, would get a tax credit worth one month's rent.

That's a confusing table of benefits whose main effect would likely be to inflate prices. Landlords could more comfortably raise rents on tenants, knowing that much of the cost increase would be absorbed by taxpayers.

Since the bill gave lower-income tenants a larger tax credit (people earning up to $25,000 could get tax credits worth all the rent they paid in excess of 30 percent of their income), rents in lower-income neighborhoods would likely rise the most under the bill.

Harris has also been a steady proponent of rent control. She praised Oregon for adopting the nation's first state-level rent controls in 2019 and endorsed Biden's recent calls for a nationwide cap on rent increases.

For its wonky reputation, housing policy really isn't that complicated. Regulations controlling what types of housing can be built where reduces production, increases prices, and limits consumer choice. Price controls make this all worse.

Rather than focus on simple supply-side solutions, Harris has leaned into ultra-complicated demand-side subsidies and rent control. That's hardly encouraging.

Gainesville Back to Posting Gains

This past week the City Commission of Gainesville, Florida, provisionally passed reforms to the city's land use code, shrinking the amount of land new homes need to consume in single-family neighborhoods.

The reforms, which passed on first reading by a 4-3 vote on Thursday, shrink minimum required lot sizes down to 3,000 square feet in a new, consolidated single-family district. The current zoning code requires minimum lot sizes of 4,300 to 8,500 square feet across four different single-family districts.

"The goal is to reduce the cost of buying or renting a single-family home in the city of Gainesville—trying to find a way to expand the amount of homes and diversity homes," says City Commissioner Bryan Eastman, who championed the reforms. By reducing the amount of land new homes require, the hope is that builders will be able to construct more affordable starter homes, he says.

Gainesville's adoption of single-family homes is notable given the city's recent history of taking one step forward and then one step back with zoning reform.

In late 2022, the city passed a slew of reforms that shrank minimum lot sizes in single-family zones and allowed property owners to build up to three units per property.

The city was promptly sued by the state of Florida under the interesting theory that allowing more housing everywhere inappropriately entrusted the free market to provide affordable housing and intruded on the state's ability to set affordable housing policy.

In the face of that lawsuit and concerted neighborhood opposition, a new city commission voted to repeal those reforms on its first day in office in January 2023.

Eastman voted against the repeal; he's been arguing for a more modest zoning reform that will still get new units built. He points to the results of minimum lot size reform in places like Houston, Texas—where minimum lot size reductions kicked off a boom in townhome construction—as a proof-of-concept.

With the caveat that we're working with small sample sizes, minimum lot size reductions have been more successful at goosing housing production than reforms that eliminate single-family-only zoning while leaving minimum lot sizes intact.

Under the latter reforms, builders have to absorb the cost of tearing down existing single-family homes in order to build slightly larger duplexes and triplexes—housing typologies that are harder to finance and market in addition to being more expensive to build.

Few of those conversions end up "penciling out," so few duplexes and triplexes end up being built.

By requiring less land per home, minimum lot size reform meanwhile makes it cheaper and easier to build single-family homes—the cheapest type of housing to build, and the easiest to finance and market.

If that's the trade-off Gainesville is making, it's probably a wise one.

A Provisional Win for Good Samaritans in Colorado

It's a tale as old as time—a local church offers shelter to the poor and indigent on its property only to have local zoning officials try to shut it down.

Such was the case in Castle Rock, Colorado, where the local The Rock church offered temporary shelter to the homeless in the form of two trailers on its property. The city contended this was a zoning violation and brought enforcement actions against the church.

With the help of the First Liberty Institute, a public interest law firm, the church sued the city in federal court in May, arguing that its ability to offer temporary shelter to the homeless is protected by the federal Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act and the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

As Reason's Patrick McDonald reported yesterday, a federal court has since sided with the church. This past Friday, it issued a preliminary injunction preventing the city from enforcing its zoning code against the church's temporary housing ministry while the lawsuit plays out.

The Birthplace of Single-Family-Only Zoning Considers a Citywide Upzoning

New York City pioneered the nation's first comprehensive zoning code in 1916. Berkeley, California, went a step further that year by passing the nation's first ordinance allowing no more than one home per lot to be built in the city's Elmwood neighborhood.

Single-family-only zoning has caught a lot of flak in recent years for walling off whole areas of cities to more housing production and commercial activity. Now Berkeley is trying to make up for its checkered land-use history.

Reports KQED:

On Tuesday, July 23, the council will consider a proposal that Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguín called "one of the largest up-zonings in California." It would go beyond what state officials allowed in a landmark 2021 law legalizing duplexes and instead permit small apartment buildings, no more than three stories high, that could range from as few as two large apartments to as many as 12 or more smaller ones depending on the size of the property.

But Lori Droste said there's no guarantee the measure will pass. The former Berkeley city council member spearheaded the city's effort to first study and then implement a plan to encourage so-called "missing middle housing."

"I'll be on pins and needles until then," she said. "I think we have a real opportunity to be history makers."

Quick Links

- California Forever, the company behind plans to build a new city in Solano County, California, has pulled a ballot initiative making the necessary zoning changes for the new city from the county's November ballot. Instead, the company and county officials jointly announced that the two parties would produce an environmental impact report and development agreement before seeking approval for the full project in 2026.

- A federal judge has dismissed a lawsuit brought by property owners in Summit, Colorado, challenging the city's restrictions on short-term rentals.

- New reports show that builders are pulling permits for far fewer single-family homes and apartments compared to this time last year.

- The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has announced the availability of $40 million in grant funds for non-profits and government entities providing legal assistance to tenants facing eviction. Taxpayer-funded legal service providers have been criticized by landlord groups for deliberately gumming up housing courts, and stretching out routine non-payment cases for a year or more.

- New York's rent stabilization law continues to crash property values of rent-stabilized buildings to rustbelt town levels.

- The Manhattan airport that could have been:

Nobody has ever cooked harder than the folks that proposed the Manhattan Airport.

And when I say "cooked", I mean meth. pic.twitter.com/xffcWke8wD

— YIMBYLAND (@YIMBYLAND) July 21, 2024

The post Coconut Trees, Price Controls, and Demand Subsidies appeared first on Reason.com.