Lawmakers are being urged to bridge the legal and scientific divide over braided rivers. David Williams reports

What is a river? More particularly, what is a braided river?

An expert group known as The Land The Law Forgot is urging politicians considering the Natural and Built Environment Bill – one of three bills to replace the Resource Management Act (RMA) – to answer those questions, and fix the dissonance between science and the law.

(The submission was provided to Newsroom by Professor Ann Brower, of the University of Canterbury’s School of Earth and Environment.)

READ MORE: * What’s fuelling our weather extremes * NZ on the cusp of a rivers revolution

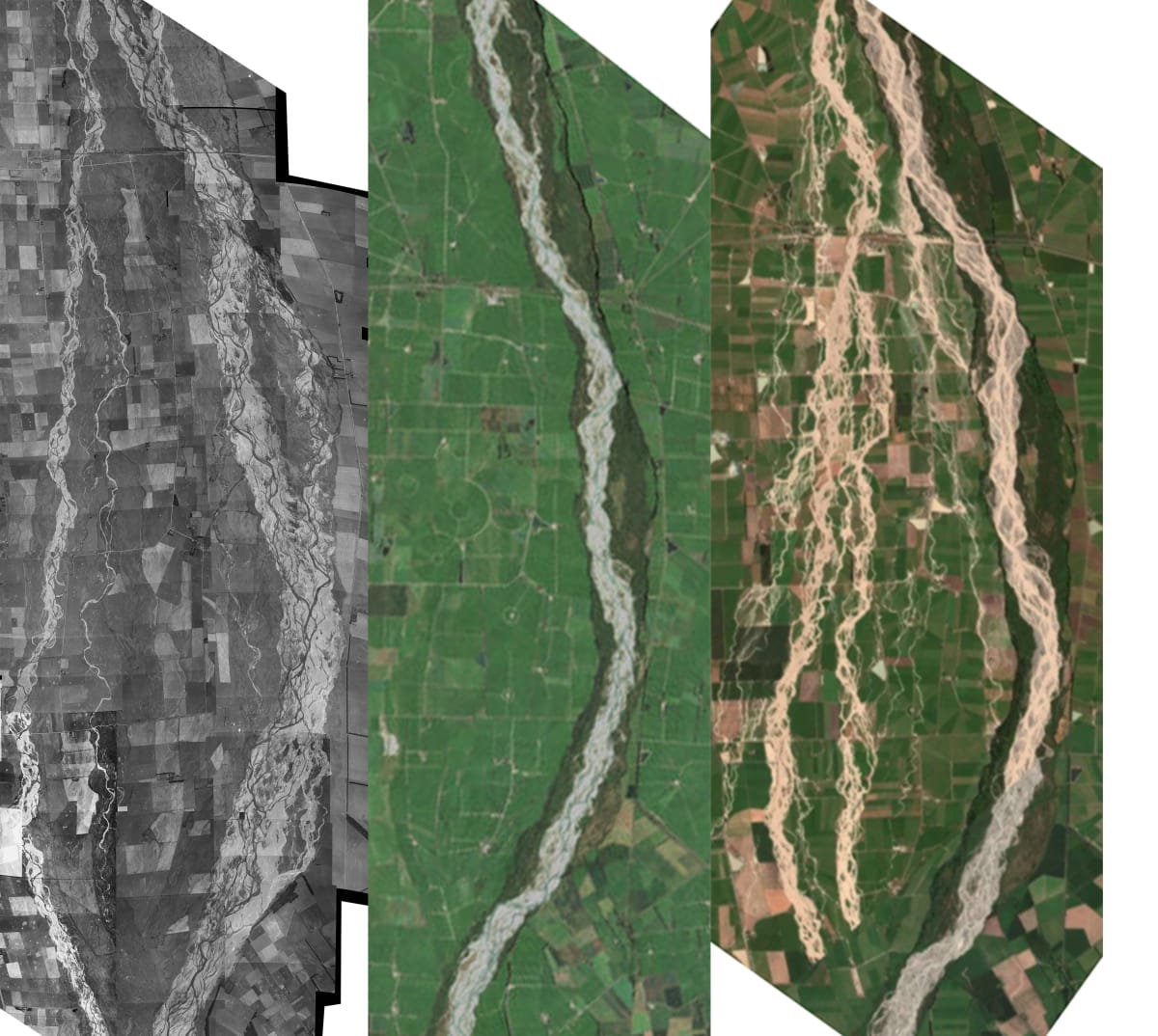

Science tells us our dynamic, complex braided rivers – of which there are 163 across the country, many of them most prominent in Waitaha Canterbury – are wet and dry at the same time. They’re prone to rapid shifts, moving from side to side, and can quickly turn from benign to threatening, as seen in the floods of 2021.

Perhaps counterintuitively, they’re also fragile and vulnerable, especially when braidplains are starved of flow by flood protection works, and encroached upon, such as for agriculture. This creep, constraining the river’s ability to adjust, can destroy a highly diverse mosaic of habitat.

Riverside areas claimed for development might be dry braids, waiting for their next activating flow, accompanied by large amounts of sediment. A past wet state is, according to scientists, a reasonable predictor of a future wet state.

The law, as the group’s title suggests, forgets – or neglects – to acknowledge a braided river’s natural character, and has defined some of its historically active areas as “land”.

The implications are many.

Māori value rivers/awa as taonga, and a loss of resilience can reduce its mauri, or life force.

Threatened and endemic species can lose habitat, leading to a loss of biodiversity.

With climate change fuelling extreme weather, encroaching on river braids puts more property and life at risk. This is because predicted larger and more frequent floods will likely inundate larger areas of their historically active braidplans.

It follows that without changes, disasters will be more costly, and adaptation, in some cases, impossible.

Without legal clarity, disasters are baked in, it’s suggested.

Right now, says The Land The Law Forgot submission, the definition in the Natural and Built Environment Bill (submissions for which closed this past Sunday night), is the same as in the RMA. That’s fine for single-channel rivers but doesn’t work for braided ones.

Their geomorphological difference should be reflected in the law, the group says.

A new definition for “braidplain” would overturn a situation that, it says, is making land and river systems more “brittle”.

Where does the land stop and the river begin?

There’s a very Canterbury context, here – one covered in an in-press article soon to appear in the NZ Journal of Environmental Law. (Two of the article’s authors, Brower and Renate Vosloo, of University of Canterbury, are also members of The Land The Law Forgot.)

It concerns a case which wound its way to the Court of Appeal in 2019.

Canterbury’s regional council, ECan, brought charges against dairy farmer Michael Dewhirst, and his company Dewhirst Land Co Ltd, for developing an area next to the Selwyn River/Waikirikiri, some of which was within riverbed.

Dewhirst extracted more gravel than a consent allowed, illegally cleared vegetation, and built a gravel bund which re-directed the river.

The farmer pleaded guilty to the charges but contested ECan’s version of events, especially whether the entire bund, and the gorse and broom cleared, were within riverbed.

Those facts were crucial to Dewhirst’s sentence, as they would determine the level of environmental harm and the seriousness of offending.

The question, “What is a riverbed”, was also precedent-setting, having implications for private landowners and public bodies, like regional councils, which are responsible for the sustainable management of rivers and their beds.

The definition determines how much land may be used, the protections afforded, and, fundamentally, when a regulator can act.

The RMA defines river “bed” as “the space of land which the waters of the river cover at its fullest flow without overtopping its banks”.

Without digging too deep into the gravelly details, the district court favoured the council’s interpretation. But as the case progressed, the higher courts’ focus seemed to narrow on the presence of water at a river’s fullest flow, versus the absence of flow.

On appeal, the High Court said the correct legal test for riverbed was from “bank to bank” – more specifically, the area within the banks covered by water during the ordinary rainy season.

The Court of Appeal referred to a common law text from 1868, which described riverbed as “the space between the banks occupied by the river at its fullest flow”.

Floods are unusual, it’s implied. This poses a problem for braided rivers, the journal article authors posit, because it excludes the presence of multiple channels, floodplains, and margins.

“The law is constrained by definitions of ‘land’ and ‘water’ that braided rivers defy,” the article says.

This lack of definitional clarity makes policy breaches hard to detect, and the position of regulators impossible. Ambiguity makes a finding of recklessness difficult for a court. If regional councils are unable to enforce rules concerning works in riverbeds that can only be bad for rivers, the article suggests.

The High Court said determining the extent of a riverbed relied on “proper application of the law, rather than in various scientific explanations”. Theory then, and legal doctrine, rather than science.

The journal article states: “There was no consideration of the river as a physical entity with unique inputs, physical geography, ecology, and history.”

In the same way that rivers are constrained by man-made stopbanks, so the Dewhirst court case constrains the way the law considers braided rivers, through a narrow definition of riverbed as “the wet area at a river’s fullest flow”.

The language is telling. When referring to natural hazards, the Court of Appeal said “there is nothing to prevent the [regional] council from controlling the use of land (which includes the flood plain)”.

There it is in black and white. A “flood plain” is “land”, not “riverbed” or “braidplain”.

In a conclusion that mirrors the submission to the Natural and Built Environment Bill, the NZ Journal of Environmental Law article says a legislative definition is needed that “embraces dynamism, complexity, and room to move”.

“Above all, to fulfil regional and national goals of protecting natural character of unique landscapes, the legislative definition must recognise that braided rivers are land and water both at once.”

Letting rivers roam

There’s scientific backing for the concept of releasing our strangled rivers.

A piece in The Conversation two years ago said we’re creating “zombie rivers” by forcing them into confined channels, and RMA reforms were an opportunity to address the problem.

“But it isn’t enough,” the authors said. Unless changes are made, people and rivers will continue on their collision course.

“Given climate change predictions of more extreme floods and drought, the problem will only get worse.”

Political debate during the first reading of the Natural and Built Environment Bill, this past November, might be instructive.

Environment Minister David Parker noted the change from an effects-based approach to one of outcomes.

“The degradation of our natural environment reduces the ability of our ecosystems to recover from shocks like the increasing storm events that come from climate change.”

National’s then climate change spokesperson, Stuart Smith, responded with a tale of the family’s Mid Canterbury farm.

“My ancestors broke that land in; they developed it. They tamed the rivers, they planted willow trees to contain the rivers within their banks, something that hadn't been done.”

The rivers “wandered all over the plains”, he said. “When people wanted to develop the land, they needed to contain them. All of that was done without a resource consent.”

Smith was making a point about long-term ties to the land. (He took umbrage at the bill recognising the relationship of iwi and hapū, which – despite Māori’s much longer connection to their ancestral lands – saying: “To single some out from others is unfair.”)

The misguided, colonial view that rivers can and should be controlled is, according to University of Auckland Professor of Environment Gary Brierley “manufacturing future disasters”.

Helping rivers roam, to occupy historic flood plains, will, in many ways, help ourselves. Part of the solution, it’s suggested, is for the law to define the beds of braided rivers to include historically active braidplains.

Then, and only then, will braided rivers stop being the land the law forgot.

Signatories to The Land The Law Forgot submission on the Natural and Built Environments Bill were:

Ann Brower, professor of environmental science, University of Canterbury

Jamie Shulmeister, professor and head of School of Earth and Environment, UC

Justin Rogers, PhD candidate in river geomorphology, UC

Aimee Calkin, MSc candidate in environmental science, UC

Alice Sai Louie, PhD candidate in groundwater hydrology, UC

Renate Vosloo, MSc candidate in environmental science, UC

Ian Fuller, professor of physical geography, Massey University

Gary Brierly, professor of physical geography, University of Auckland

Dr Jo Hoyle, fluvial geomorphologist, NIWA

Rasmus Gabrielsson, chief executive of North Canterbury Fish & Game Council

Dr Philip Grove, terrestrial ecologist

Dr Duncan Gray, freshwater ecologist