The conflict in Ukraine will have far-reaching economic consequences. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research forecasts that it could knock one percentage point off global GDP in 2023 – equivalent to around a trillion US dollars or £760 billion. The UK will be buffeted by the impacts of rising inflation, driven by soaring energy prices, which will squeeze household incomes and weigh on the recovery.

The UK’s chancellor, Rishi Sunak, may decide that his previous £9 billion package of support for households no longer looks sufficient. That’s likely the main topic of discussion within the Treasury in the run-up to the spring statement on March 23.

But the conflict could have another, less immediate but perhaps more substantial, effect on the government’s fiscal position. Namely, what if Russia’s invasion of Ukraine means that we need to spend more on defence?

The great peace dividend

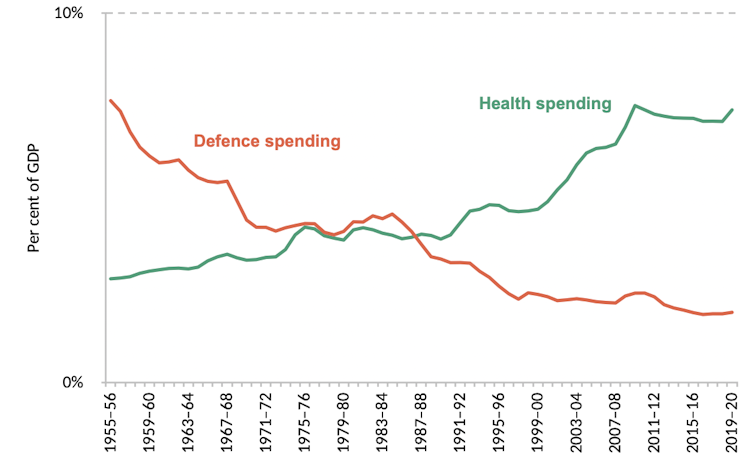

The UK currently spends slightly over 2% of GDP on defence each year, amounting to some £45 billion in 2021, or about £660 per person. This has fallen substantially over time. In the mid-1950s, the UK spent almost 8% of GDP on defence. That fell to about 4% in 1980, 3% in 1990, and around 2% today. At the same time, spending on the health service has grown from around 3% of GDP in the mid-1950s to more than 7% on the eve of the pandemic.

The “peace dividend” from lower spending on defence has, in effect, allowed successive governments to pay for a growing welfare state without having to increase the overall size of the state. In other words, more healthcare without a higher tax burden. That’s been a handy trick – but you can only repeat it for so long.

Defence spending had already stopped falling in recent years because the government has pledged, as a Nato member, to spend at least 2% of GDP on defence each year. That’s why to finance additional spending on health and social care, the UK government is putting up National Insurance contributions in April.

UK spend on health and defence as % of GDP

In fact, the UK is one of only a handful of countries to have consistently met the Nato pledge. Between 2014 and 2021, the UK had the third-highest average defence spending as a fraction of GDP (at 2.1%), behind only Greece (2.6%) and the United States (3.5%). Other countries, including France (average 1.9%), Germany (1.3%), Italy (1.2%) and Spain (0.9%) consistently spent less – and in some cases much less – than the Nato target.

That might be about to change. The German chancellor, Olaf Scholz, has announced a “new era” for his country’s defence spending, promising to invest €100 billion (£82 billion) in the German military and to spend at least 2% of GDP on defence in every year going forward. Other countries are talking about following suit.

This raises questions about whether the Russia-Ukraine conflict will necessitate any additional British military spending. Even if it doesn’t trigger a direct response, the shift in German policy could feasibly lead to a similar decision in the UK.

The UK calculus

In dollar terms, the UK (US$73 billion in 2021) is currently the second biggest spender in Nato after the United States (US$811 billion). A government committed to projecting the power of “Global Britain” might wish that to remain the case.

If Germany succeeds in meeting its 2% of GDP target, the UK would need to boost its own spending by around 20% to retain its number two spot within Nato. That is substantial, even if it would fall short of the 25% increase that Jeremy Hunt, the then foreign secretary, called for in 2019 in his bid to become leader of the Conservative Party.

Deciding whether to go down this road is a policy question for the medium term. A more pressing question might be whether to cancel the modest real-terms cuts planned for the Ministry of Defence (MoD) over the next three years.

The MoD was the only department on the receiving end of budget cuts at the government spending review in October 2021. Higher inflation will add to the squeeze. In particular, the MoD spends around £600 million per year on energy and fuel, and so is exposed to the spike in global prices. On top of that, the ministry has an annual pay bill of around £15 billion, and can expect calls for larger pay increases to protect the real-terms pay of members of the armed forces.

For Sunak, calls for higher military spending in response to Russian aggression will be just one of many demands he faces ahead of this month’s spring statement. In the longer term, if the UK does end up permanently spending more on defence, that would mark a break with the pattern of the past 70 years. It would also ultimately mean either spending less on something else, or higher taxes.

Ben Zaranko works for the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). The IFS is non-profit and non-political and receives funding from a range of sources, including the Economic and Social Research Council, UK Government departments, foundations, the European Research Council, international organisations, companies and other non-profit organisations. For full details, see: https://ifs.org.uk/about/finance

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.