If Russia were a human being, then it would have an almost pathological fear of threats to its person. As is often the case with fear, it has a kernel of grounding in reality, but has grown completely out of proportion under President Vladimir Putin.

Few people, including me, regard these fears as anything close to sufficient justification for Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The West has not presented even an abstract military threat to Russia since the end of the Cold War.

There is no doubt, however, that the expansion of western influence eastwards through NATO and the European Union does present an existential threat of sorts to Putin’s notion of Russia.

Russia’s relationship with the West has a rocky history. Russia has for much of its existence feared military threats from the West — a fear that has gone hand-in-hand with suspicion of western norms and ideas such as liberal democracy.

Russia repelled Napoleon

Russia defeated Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of 1812 even though Napoleon’s forces reached Moscow. By 1814, Russian troops were in Paris, an important element in the coalition against Napoleon. Russia under Czar Alexander I was at the height of its power and influence.

While the defeat of Napoleon brought Russia some military security, it didn’t bring psychological security for the czars. Russian soldiers had seen some of the rest of Europe, and were thought by Russian conservatives to be bringing back dangerous western ideas that might undermine the status quo in Russia.

Indeed, an uprising in 1825 against the new czar, Nicholas I, by the so-called Decembrists was seen as having been influenced by western ideas that had been brought back from the war against Napoleon.

For much of the remainder of the 19th and early 20th century, Russian czars fought a battle to preserve a Russian way of life they believed was under threat from foreign ideas.

At times, the foreign threat was again a military one, as in the Crimean War of 1854-55. Before long, repressive measures against previously content national minorities within the Russian empire, such as the Finns, exacerbated internal problems.

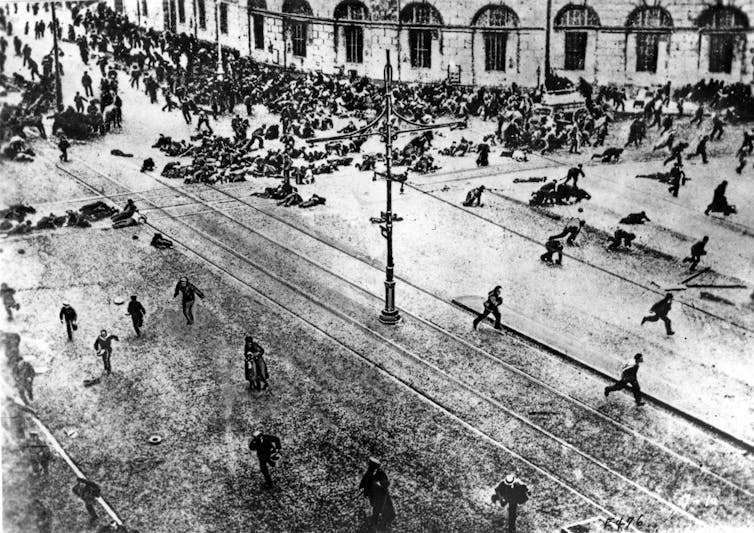

Bolshevik Revolution

All of this in many ways culminated with the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 — made possible thanks to Russian weaknesses during the First World War. The Russian economy just wasn’t up to fighting a modern industrial war, and the czarist regime had managed to alienate itself from almost every major segment of the Russian population.

The Bolsheviks, however, were soon faced with — and became obsessed about — foreign threat. During the Russian Civil War that lasted until 1921, western powers — primarily Great Britain, the United States, France and Canada — united against the new Bolshevik regime and sent troops to Russia.

Although the Bolsheviks were able to consolidate their power by 1921 and formed the Soviet Union at the end of the following year, there remained an obsession with the threat of being surrounded by hostile foreign powers.

Soviet fears of the West’s military strength and other threats lasted for most of the history of the Soviet Union. Nazi Germany’s ultimately unsuccessful invasion in June 1941 took place at a time when the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany were supposed to be allies, and the German aggression enhanced Russian mistrust of foreign promises.

By 1944, the Soviet Red Army had recovered Soviet territory from Germany and her Axis alliance partners, and was in a position to sweep across eastern Europe. In doing so, the Red Army was helped by its temporary American and British allies who were both fighting in the West and providing the Soviet Union with material assistance.

That alliance did not last long after the Second World War as differences between the Soviet outlook on the world and that of its allies resurfaced as what is known as the Cold War.

The Warsaw Pact

Josef Stalin at least now had a cordon of “friendly” countries in eastern Europe — including Poland and Czechoslovakia — as a buffer between the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (the USSR) and the West. Those countries would become members of the Warsaw Pact.

Throughout all of this, the Russian empire — then the Soviet Union — had a territorial core that was largely unbreakable. Although Ukraine had been very briefly independent during the revolutionary period, it had been forcibly brought back into the fold.

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was a key member of the Soviet Union, alongside Belorussia. Russians, Ukrainians and Belorussians, along with the Soviet peoples of the Caucasus, Central Asia and even some from the recently incorporated Baltic republics, fought together to rid the Soviet Union of the Nazi invaders.

After the Second World War, many citizens of the USSR viewed themselves as Soviet along with their specific national cultural identity — something that lives on even today in the wartime generation born and raised during the Stalinist period.

Apparent Soviet strength in the aftermath of the Second World War was not enough, however, to suppress Soviet insecurities. Stalin had a deep fear of foreign influence stemming from contacts with the West during the war. In the late 1940s, Stalin singled out and attacked Jews as “rootless cosmopolitans” and suspected pro-westerners.

Fears of being undermined

For much of the remainder of the Cold War, Soviet leaders were fearful of western influence and technological superiority. Both the experience of western intervention during the Russian Civil War and the perfidious Nazi invasion gave the Soviet Union something of a complex about being undermined by the West — via military might or otherwise.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 is considered a disaster by many Russians — including Putin. Events since 1991 have seen a steady erosion of Russian influence in its own backyard and an expansion of not only western ideas but also the NATO military alliance.

Western promises that NATO would not expand beyond Germany were broken, and now Putin sees Russia as under siege.

His invasion of Ukraine is a last-ditch attempt to stave off western influence over territories that Russia has historically dominated.

Putin’s Russia — and Putin himself — is like a cornered animal apt to lash out. The West needs to be exceedingly careful about how it pokes that animal given Russia’s nuclear capabilities. Putin’s Russian government has a long memory of resentment towards what it sees as its western assailant, and is no longer acting with the restraint it was showing a decade ago.

Alexander Hill does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.