A deadly E. coli outbreak linked to romaine lettuce ripped through 15 states at the end of last year, but the Food and Drug Administration didn’t publicly disclose it, according to a report.

The outbreak was linked to the death of one person and hospitalized 36 people in November, including a 9-year-old boy who nearly died of kidney failure.

An internal report obtained by NBC News revealed that the agency did not name the produce company involved in the outbreak and they did not share information with the public about it.

“There were no public communications related to this outbreak,” the report said, and added that the company in question “was not named during this outbreak because there was no product remaining in commerce.”

Data connected 89 cases across 15 states and concluded that romaine lettuce was the source of the outbreak, the Food and Drug Administration’s report concluded.

Questions are now being asked about why the agency decided to keep the outbreak quiet – and critics have pointed out that many employees responsible for distributing information to the public about foodborne illnesses recently lost their jobs in the Trump administration’s purge of the federal government.

“We no longer have all the mechanisms in place to learn from those situations and prevent the next outbreak from happening,” Taryn Webb, who led the agency’s public engagement division for human foods until she lost her job in the sweeping cuts this month, told NBC News.

“It is disappointing, but with 20,000 employees at Health and Human Services being fired, investigating, and reporting on outbreaks and alerting the public to the cause is clearly not a priority for this administration,” food safety attorney William Marler said.

“If the gutted CDC and FDA can no longer do the job, we will step up to inform and protect the public – so much for ‘Make America Healthy Again,’” he added.

Officials are not required by law to publish information about all known outbreaks of foodborne illnesses and in some cases, the agency may decide to hold back on publishing information when the cause is still unknown.

“The FDA names firms when there is enough evidence linking an outbreak to a firm and there is actionable advice for consumers, as long as naming the firm is not legally prohibited,” a spokesperson told NBC News in a statement. “By the time investigators had confirmed the likely source, the outbreak had already ended and there was no actionable advice for consumers.”

The Independent has contacted the Food and Drug Administration for further comment.

But food safety advocates argue that the agency’s response is not good enough. “It is disturbing that FDA hasn’t said anything more public or identified the name of a grower or processor,” Frank Yiannas, who was the agency’s deputy commissioner of food policy and response from 2018 to 2023, told the outlet. He added that the agency has shifted toward greater transparency in recent years when it comes to disclosing information about large-scale outbreaks.

“People have a right to know who’s selling contaminated products,” Sandra Eskin, a former official at the U.S. Agriculture Department, added.

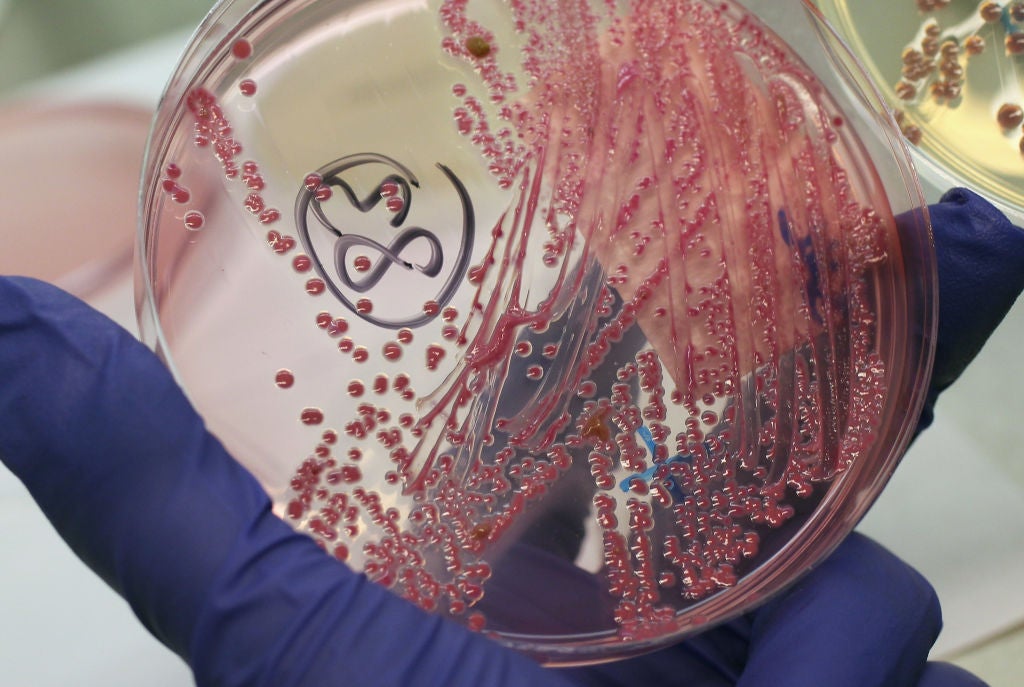

Cases started popping up across Missouri and Indiana in November. The strain was identified as a particularly dangerous one – E. coli 0157: H7. The rare strain can result in organ damage and even death in some exceptional cases.

High school students living in Missouri’s St. Louis County were affected after eating salad at a school event. Families reported that their children were suffering from violent stomach cramps, bloody diarrhea and vomiting.

In Indiana, the same strain almost killed 9-year-old Colton George, who woke up doubled over in pain. He was hospitalized for two weeks, including on his 10th birthday, after developing hemoltyic uremic syndrome. He was put on round-the-clock dialysis. George still suffers from chronic stomach pain and fatigue, his family told NBC News.

The E. coli outbreaks in both states are linked by the same genetic sequencing, according to a lawsuit filed by the George family.

Outbreaks also occurred in Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Montana, North Dakota, Nebraska, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Tennessee and Wisconsin, the Food and Drug Administration’s report said.

Food safety law firm Marler Clark has filed a suit against Taylor Farms, one of the largest producers of salads and fresh vegetables in the U.S., and alleges that’s where the tainted lettuce originated.

Taylor Farms denied the allegation in a statement to NBC News. “We don’t believe Taylor Farms was the source of the referenced recent E. coli outbreaks, based on information collected during thorough third-party investigations and robust food safety controls,” the company said in a statement.

The Independent has reached out to Taylor Farms for further comment.

Nine other lawsuits argue in court papers that Taylor Farms sold “defective and unreasonably dangerous” produce, NBC News reports.

Draft budget plan proposes deep cuts across federal health programs

Behind the story of the decades-long journey of xenotransplantation

Warning issued over common blood pressure drug after labelling error

What is Type 5 diabetes? New form of disease recognised after decades of debate

Daily weight-loss pill may work as well as Ozempic and could replace injections