On 24 November 1971, a man boarded a flight to Seattle, Washington, from Portland, Oregon. His plane ticket – bought with cash – identified him as Dan Cooper, though that later turned out to be a fake name.

Shortly after 3pm, the man handed a stewardess a note indicating that he had a bomb in his briefcase and demanding that she sit with him. According to the FBI’s account of the story, “the stunned stewardess did as she was told. … Soon, she was walking a new note to the captain of the plane that demanded four parachutes and $200,000 in $20 bills.”

The man got what he wanted. Now known under the nickname DB Cooper, he became the perpetrator of the only unsolved plane hijacking in US history, jumping out of the Boeing 727-51 with a parachute and the ransom money, which would amount to $1.3m nowadays.

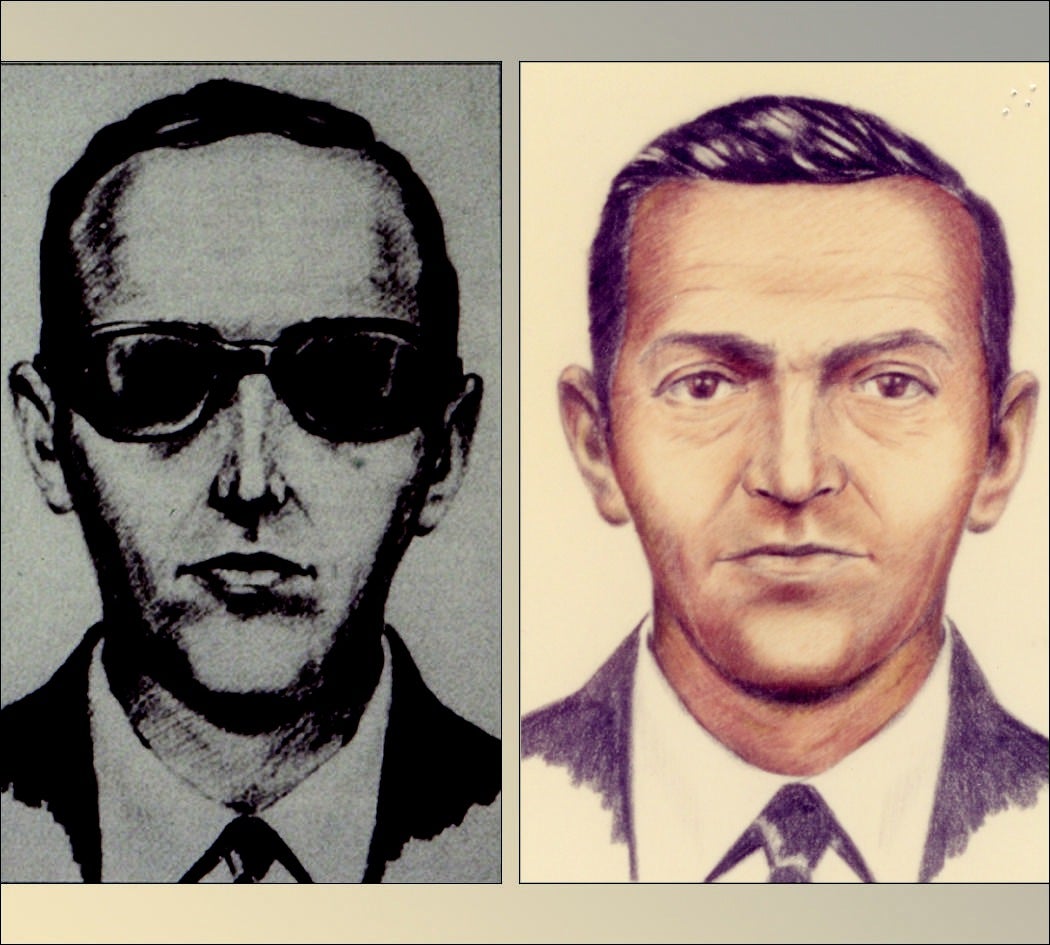

DB Cooper – the incorrect nickname emerged due to a miscommunication in early news reports and stuck – was never seen again. He has never been identified, much less arrested. Because of those mysteries, his story has become a folktale of sorts. Cooper’s identity has been the subject of decades of speculation. He has been referenced in novels, TV series, and films. If the story of this hijacking is a solar system, Cooper has been its bright, burning sun.

Fifty years on, a team of people is trying to reframe the narrative. Chief among them is Tina Mucklow. She was one of three flight attendants on board when the plane took off, and the only one left in the aircraft by the time Cooper escaped. After decades of silence, she’s finally ready to share her story. It will be told in a film titled Nod If You Understand, expected to enter production in 2022, with Amber Sealey (whose film No Man of God about the last days of Ted Bundy came out in August) directing. In the interim, Mucklow is speaking out too. “I still can feel things as I remember them in detail,” she tells The Independent. “I still get goosebumps at times.”

Mucklow, now 72, was 22 years old on the day of the hijacking, the most junior crew member on the aircraft. There were 42 people on board – three flight attendants, three pilots, and 36 passengers, including the hijacker. As crew members were preparing for takeoff, Mucklow’s coworker Florence Schaffner got up to sit next to another person (who turned out to be Cooper) in row 18. While doing so, she dropped a note at Mucklow’s feet. “I picked it up, and it basically said, ‘Miss, I have a bomb, come sit next to me, you’re being hijacked,’” Mucklow says. The fact that Schaffner had just got up to trade seats – “totally not normal procedure” – told Mucklow the threat was real.

“We’re being hijacked, and this is not a joke”

“The intercom system was right next to me. I reached over and grabbed the phone,” she recalls. Mucklow called the cockpit using an emergency signal, which wasn’t supposed to be used this early on in the flight, while the plane was still taking off. “I just started to talk,” she says. “I said, ‘We’re being hijacked, and this is not a joke.’”

Mucklow recalls the events that followed in vivid detail. She remembers where she and her colleagues sat, what was said and when. In her recollection, she never refers to Cooper by name. He is “the hijacker”. He is the man who threatened 41 people’s lives in exchange for money.

“He opened the briefcase and showed me the bomb,” she says. “He explained how it would work. I think I was probably in shock. Then he had his hand in the briefcase, kind of closed it, and looked out the window.”

Mucklow’s mind got to work. “I was like, ‘What am I going to have to do to handle the situation? What am I going to have to experience? There will be an explosive decompression. Stuff’s going to fly in the cabin,’” she recalls. “And then, all of a sudden, I was like, ‘Oh, I’m not going to have to worry about any of this. I’m not going to be here.’ When that hit me in the face, I tried to recognize that my life was probably at the end. And my first thought was I wanted to run, which is a perfectly normal reaction. But there was no place to run.”

Mucklow thought of the passengers, of the destination they might never reach, of the plans they might never fulfill. “I started to pray,” she says. “I prayed for the passengers and their families. I prayed for my own family, thinking that I would never see them again. I prayed that they would understand. I prayed for my own forgiveness, for all the faults and shortcomings.”

As she did that, she turned her gaze to the hijacker. “I was looking at him to the side, and I was thinking to myself, ‘He’s willing to take the lives of all these people.’ I started to pray for him, and there was just a sense of peace. I never really thought about my own mortality from that point on.”

“They didn’t want us to rain down on people”

Mucklow became Cooper’s point of contact, managing his demands, communicating with the cockpit, and trying to act as a “barrier” between the hijacker and the passengers. The cockpit asked air traffic controllers for a holding pattern – an area they could circle while the items Cooper had requested, the cash and the four parachutes, were being collected. They were told to keep flying over Puget Sound, a body of water near Seattle, “because if anything happened,” Mucklow explains, “they didn’t want us to rain down on people”.

Throughout their interactions with Cooper, Mucklow and her colleagues tried to be “respectful of the hijacker”, making sure he was feeling “comfortable” and that crew members “were going to work with him”. “He wanted his demands met by a certain time, which posed a huge problem for the people on the ground,” Mucklow says. “There were several times when he got really upset, and I tried to keep him calm and reiterate that we were doing the best we could and trying to give him as much information as possible.”

The rest of the passengers, meanwhile, didn’t know there was a man with a bomb on the plane. As far as they knew, they were on a normal flight. They had regular demands. Some wanted to use the bathroom. One passenger asked for a sports magazine. Mucklow, of course, couldn’t tell them why she was busy, or why they shouldn’t do certain things. “I couldn’t give away that we were dealing with a life-and-death situation back here,” she says. When Cooper got annoyed at the flurry of passenger activity, she once again tried to reassure him. She would always be near him, she told him. She would stand up. She would be a “blockade” between him and the other people on board.

By then, a plan was in place to land the aircraft to collect the cash and the parachutes. The hijacker had requested a fuel truck too, so that the plane could take off again. Once they were airborne again, he would jump out using one of the parachutes.

The Boeing landed in Seattle. Mucklow and her coworkers had moved as many passengers to first class by that point, telling them only that the plane was experiencing a minor mechanical issue. Cooper, Mucklow recalls, had designated her to collect the cash. “So I did,” she says. “I went off and got the money.” The person handing her the money was a man named Al Lee, the airline’s operations manager for Seattle. “There was a moment when the two of us kind of had eye contact. I was only 22, so he looked more like a father to me,” she recalls. “He said, ‘Are you okay?’ I had to blink back tears, and I said, ‘I’ll be okay.’ And I took the money and went back on the airplane.”

How could she possibly have found it in herself to go back inside the plane, when she knew her life would be at risk? “The passengers were still on board,” she says. “The lives of the passengers were our number one priority.” Once they saw the money being delivered on board in a knapsack, she muses, they must have got a sense that the plane was not just dealing with a small mechanical issue. Still, they stayed seated. Mucklow delivered the money and asked the hijacker for permission to let the passengers off. He granted that permission. Eventually, the other two flight attendants – Schaffner and another employee called Alice Hancock – were released too. Only Mucklow and the three pilots were left with Cooper when the plane took off again.

“I felt so alone”

Cooper had wanted the stairs at the back of the plane to be lowered during takeoff, but when the crew members argued they couldn’t take off with the stairs deployed, it was decided they would instead take off with one door open, and that the stairs would be lowered while in the air.

“I was terribly loud and eerie to have the door open during take off,” Mucklow recounts, “and the airplane was totally dark in the back. I felt so alone at that point.”

The hijacker told Mucklow to show her how to lower the stairs, then told her to go to the cockpit. Mucklow and the three pilots were to stay away from that point forward, not watching while Cooper supposedly lowered the stairs and jumped out.

When the plane finally landed in Reno, Nevada, with the back staircase deployed (an indication that Cooper had carried out that part of his plan successfully), it was unclear whether he had actually jumped or whether he was still on board. Once it looked relatively safe to come out, Mucklow stepped off the aircraft. “Pretty soon, a car came up, and they were like, ‘Who are you?’” she recalls. “I said, ‘I’m one of the crew. Who are you?’ And they said, ‘We’re the FBI.’”

Two cars came to drive the four remaining crew members away. It wasn’t until she sat at the back of one of the vehicles, Mucklow recounts, that “the dam broke”. Photos of the crew taken right after their landing in Reno show her as a shell-shocked 22-year-old, shoulders hunched, face blank. Because no one died, the hijacking is often painted as a victimless crime. Cooper, we are told, got on a plane, made some demands, got away, and didn’t hurt anyone physically along the way. This is all true, but there is something missing from that view. Trauma is a form of victimization too.

“I wasn’t going to be defined by this”

After the hijacking, Mucklow asked to go home to visit her family. She did so, then returned to work as a flight attendant in December of 1971. Mucklow stayed in that line of work until 1980. By then, she had embraced Catholicism after being raised Protestant, and entered a monastery. She was a nun for a few years, then left the monastery and worked in social services, holding several positions in the field of mental health until her retirement. In the background, as the FBI failed to identify the perpetrator, the story of the hijacking became the story of DB Cooper, a folktale of sorts and a perpetual subject of fascination.

“It has been a sad journey,” Mucklow says, “to think that somebody who was a criminal and put the lives of the crew and the passengers at risk, plus those of any number of people on the ground, would be looked at as a hero.” The hijacker, she points out, did a considerable amount of damage – not just that day, but in the years and decades that followed. In the history of commercial aviation, the 1971 hijacking is considered one of the events that marked the beginning of the more scrutinized, heavily regulated form of air travel we know today.

Five decades on, Mucklow still gets phone calls and letters from people trying to solve the case. “I understand wanting to solve the crime, but I think they were very disrespectful of me and the other crew members too,” she says. “But I wasn’t going to be defined by this. I moved on with my life and I enjoyed the things that I had the ability to do.” Even in the immediate aftermath of the hijacking, she still loved flying. She does to this day.

Up until now, Mucklow has largely avoided the public eye. She only got involved with the new film project after producer Joey McFarland (whose past work includes The Wolf of Wall Street and Papillon) tried to call her – twice – and ended up leaving a voicemail making it clear he wasn’t interested in DB Cooper, but in Mucklow’s own story. “She called me back within an hour,” McFarland says. From there, he and producing partner Dawn Bierschwal (the two are also co-writers on the film) worked with Mucklow, meeting her in person several times, listening to her story, and diving into the case archives. (The FBI announced in 2016 it had “redirected resources allocated to the DB Cooper case to focus on other investigative priorities”, but a wealth of records remains available online.)

“When you read accounts [of the hijacking] online, it looks like Tina just sat there and stayed calm,” Bierschwal says. “But she did so much more. She’s super humble, so she’s not going to volunteer that she was a hero, but she is in fact one. She used her wit, her sense of humor, and other things to influence the hijacker and save the passengers and crew. She got off the plane, and yet she chose to get back on to save the passengers. There were so many things she did.”