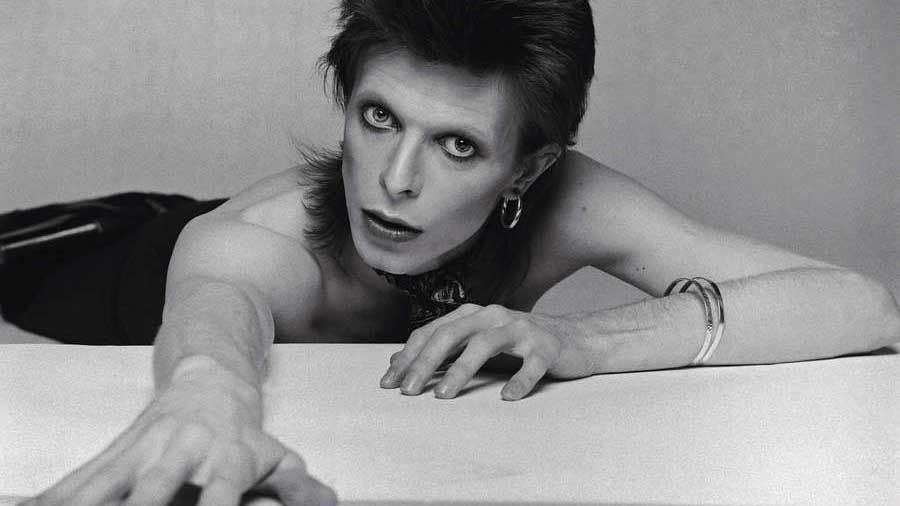

Released in the summer of 1974, Diamond Dogs found David Bowie navigating the dog days of the glam-rock era – a hot and sultry period before the cultural weather broke. Having surfed and defined the pop zeitgeist about as well as any individual star since Elvis Presley, he was now cresting the last stretch of a wave as it came crashing into shore.

Diamond Dogs was a resounding commercial success – No.1 in the UK, No.5 in the US. But the album was marked down at the time. “A rather grandiose mood piece… It’s okay, you know, but is it really necessary?” was the NME’s verdict. And, retrospectively, it tends to get brushed aside in the grand sweep of things as a transitional album, marking the point in Bowie’s artistic timeline at which he was shedding his glam-rock skin and stepping into his role as the ‘plastic soul’ man of his next studio album Young Americans. (NME later revised its opinion and, in 2013, rated Diamond Dogs one of “The 500 Greatest Albums of all Time” – albeit ranked at No.447, a long way behind many of his other albums.)

Bowie himself was quick to recognise the record’s limitations. “It was not a concept album,” he told Robert Hilburn in September 1974. “It was a collection of things. And I didn’t have a band. So that’s where the tension came in. I couldn’t believe I had finished it when I did. I had done so much of it myself. I never want to be in that position again. It was frightening trying to make an album with no support behind you. I was very much on my own. It was my most difficult album. It was a relief that it did so well.”

Whatever the sense of “tension”, both musically and personally, which overshadowed the making of Diamond Dogs, the album is nevertheless a remarkably pure distillation of Bowie’s genius. Indeed, if you are looking for a collection of recordings that stands as a monument to Bowie’s across-the-board prowess as a songwriter, singer, guitarist, saxophonist, keyboard player, producer and allround media maven, there is no other album in his entire catalogue that compares to Diamond Dogs. Transitional or not, it remains as true an expression of his artistry on every front as anything he ever released.

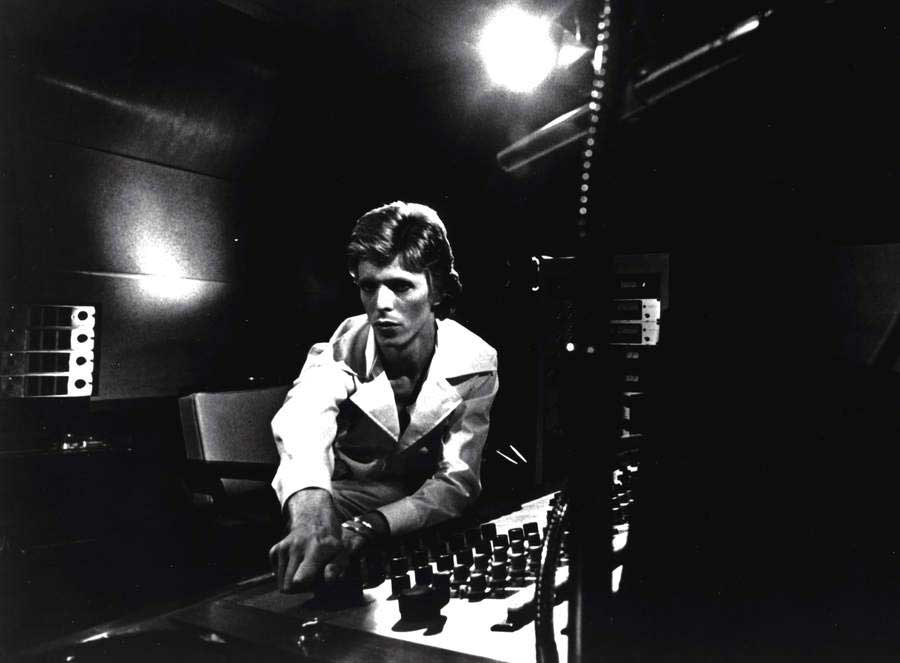

The album was recorded in London, mostly at Olympic Studios, and Hilversum in the Netherlands, between December 1973 and February 1974. Having famously disbanded the Spiders From Mars live on stage at Hammersmith Odeon the previous July, Bowie’s first challenge was to fill the guitar genius-shaped hole left in his musical life by the departure of Mick Ronson. In a defiant display of ambition and bravado, Bowie resolved to do the job himself.

“I knew that the guitar playing had to be more than okay,” he said, looking back in 1997. “That couple of months I spent putting [Diamond Dogs] together before I went into the studio was probably the only time in my life where I really buckled down to learn the stuff I needed to have on the album. I’d actually practise two hours a day.”

Having also dispensed with the services of longstanding producer Ken Scott, Bowie’s initial plan was not only to produce the album but also to play every instrument himself – perhaps reaching the point at which ambition gave way to hubris.

Wiser counsel prevailed and he found a new rhythm section comprising session bass player Herbie Flowers (the man responsible for the swooping bass line on Lou Reed’s Walk On The Wild Side) and drummer Tony Newman (best known for his stint in the Jeff Beck Group). Pianist Mike Garson and drummer Aynsley Dunbar, who had both contributed to Pin Ups, the album of cover versions which Bowie had somehow slotted into his schedule and released in October 1973, were also brought in.

All sorts of grand ideas were floated in the build up to Diamond Dogs. Bowie had spoken of his intention to mount a “full-scale rock musical” re-telling the story of Ziggy Stardust. He’d also let it be known that he was planning to write and direct a musical production for TV of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, one of his favourite novels.

“I’d failed to obtain the theatrical rights from George Orwell’s widow,” Bowie told the Mail On Sunday in 2008. “And having written three or more songs for it already, I did a fast about-face and recobbled the idea into Diamond Dogs: teen punks on rusty skates living on the roofs of the dystopian Hunger City; a post-apocalyptic landscape.”

The scene is set on the opening number, Future Legend, a brief, howling, growling, synthesised soundtrack with a voiceover from Bowie introducing us to a ghastly, ruined cityscape where ‘Fleas the size of rats sucked on rats the size of cats/ And ten thousand peoploids split into small tribes…’ The recitation ends with the jarring proclamation: ‘This ain’t rock and roll. This is genocide!’ The title track, which follows, actually sounds a lot more like rock’n’roll than mass murder – with an influence that owed a noticeable debt to Mick Jagger and Keith Richards.

As chance would have it, the Rolling Stones were in Olympic Studios recording their album It’s Only Rock’n’Roll at the same time as Bowie was working on Diamond Dogs. Olympic’s in-house engineer, Keith Harwood, who engineered Diamond Dogs, had previously worked on several Stones albums.

And if the general fraternising that went on during the course of the sessions wasn’t enough to reinforce the connection, Bowie and his then-wife Angie (Angela Barnett) had recently moved into a grand terraced house in Chelsea where they were now near neighbours of Mick and Bianca Jagger, with whom they socialised. Indeed, according to the American singer and model Ava Cherry, who stayed in the house for a time with David and Angie, there was a lot more than socialising going on.

“Mick Jagger knew David, and I was friends with both of them,” Cherry told Bowie biographer Dylan Jones. “So all three of us used to hang out a lot, and yes we did have some fun together.”

According to Cherry, at the end of one party in New York, everyone had left apart from her, Bowie and Jagger. “So it just ended up with the three of us sleeping together. That was it. And we had a wonderful time and we had a lot of fun.”

Diamond Dogs performed disappointingly when released as a single in June 1974 (after the album was released) in the UK, where it peaked at No.21. Far more resonant and enduring as a flagship track for the album was Rebel Rebel – the song that most clearly marked both the end of an era for Bowie and the jumping off point for Diamond Dogs.

Recorded on December 27, 1973, Rebel Rebel was the first song of the sessions and the last song that Bowie recorded at Trident Studios in Soho where he had recorded the majority of his work since 1968. Released as a single in the UK in February 1974, ahead of the album, Rebel Rebel reached No.5 and remains one of Bowie’s touchstone songs.

The lyric is as pertinent today – maybe even more so – as it was almost 50 years ago: ‘You’ve got your mother in a whirl, cos she’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl.’ And the riff is a masterpiece: simple, original and instantly recognisable in the way that only a handful of pop-rock riffs – Sweet Jane, Jumping Jack Flash, You Really Got Me – could ever truly claim to be. Did Bowie really come up with that and play it completely off his own bat?

“He had the riff about seventy-five per cent sorted out,” recalled Alan Parker, a session guitarist credited for his contribution to one track (1984) on the album. “He wanted it a bit like a Stones riff and he played it to me as such, and I then tinkered around with it. I said: ‘Well, what if we did this and that and made it sound more clangy and put some bends in it?’ And he said: ‘Yeah, I love that, that’s fine.’”

Whatever Parker’s contribution to the sculpting and performing of the song behind the scenes, Bowie is the sole writer and guitarist listed on the credits. While Rebel Rebel and the title track echoed the triumphs of Bowie’s glam-rock past, the rest of the album offered a tantalising glimpse of the future-Bowie that was yet to fully materialise.

At the heart of Side 1 is the three-piece song suite Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (Reprise), which was originally intended to be the centrepiece for the would-be stage production of Nineteen Eighty-Four. It is a yearning yet chilling sequence, with lyrics rendered as a collage of bittersweet images and ideas. ‘I guess we could cruise down one more time, with you by my side it should be fine/We’ll buy some drugs and watch a band, then jump in the river holding hands.’

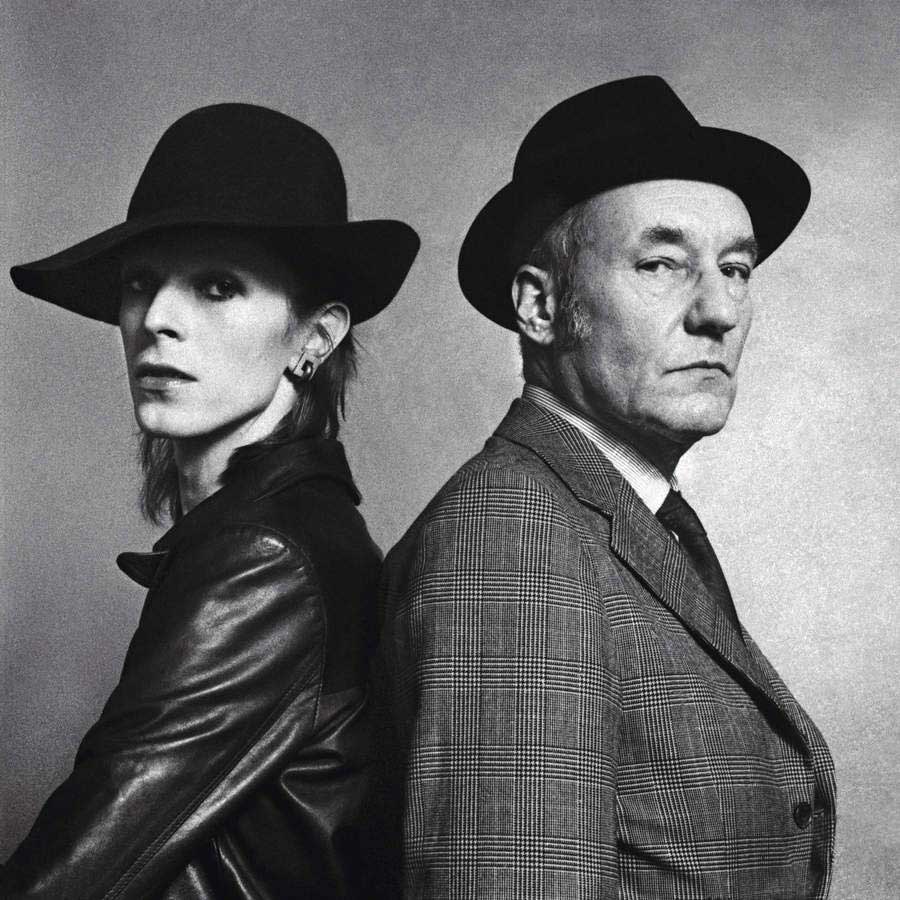

The sequence is notable for its intensely detailed arrangement – brought to life not least by Bowie’s contributions on saxophone and guitar. The end of the Reprise section (which runs into Rebel Rebel) has him conjuring a screeching, crunching, overdriven guitar noise that prefigured the industrial sounds that Earl Slick would later develop on Station To Station and Reeves Gabrels would take to another level on the Tin Machine albums. Bowie wrote the lyrics for these and other songs on Diamond Dogs using the ‘cut-up’ method popularised by the ‘beat’ writer and literary figurehead William Burroughs.

“You write down a paragraph or two describing several different subjects,” Bowie explained. “Creating a kind of story ingredients list, I suppose. And then cut the sentences into four- or five-word sections; mix ’em up and reconnect them. You can get some pretty interesting idea combinations like this.”

While the mood and subject matter of the songs on Side 2 is clearly derived from the nightmarish gloom of Orwell’s novel, it is impossible to know where and how these cut-ups might have been made or what the precise meaning is. ‘We’re today’s scrambled creatures, locked in tomorrow’s double feature, heaven’s on the pillow, its silence competes with hell/It’s a twenty-four-hour service guaranteed to make you tell…’ Bowie sings mournfully on We Are The Dead. It certainly soundslike a bad trip.

The comparatively jaunty music on tracks such as Rock’N’Roll With Me and Big Brother sounds like it should be part of a stage musical – as indeed it was originally intended to be. The Rocky Horror Show, which opened at the Royal Court Theatre in London in 1973, was on the way to becoming a cult phenomenon at the time Bowie was writing the album and there was a lot of musical theatricality in the air.

There was also evidence of the looming switch of musical pace and persona that Bowie would effect on his next album, Young Americans – most obviously represented in the track 1984, which took its inspiration from the wah-wah guitar and string arrangements of Isaac Hayes’s soundtrack to the 1971 film Shaft.

“When we worked on the song 1984 he was already referencing Barry White,” said Ken Scott, who had produced an earlier recording of the song as part of the Aladdin Sane sessions in January 1973. “He wanted the hi-hat and the strings to sound like they would be on a Barry White album. He was already anticipating the sound of Young Americans.”

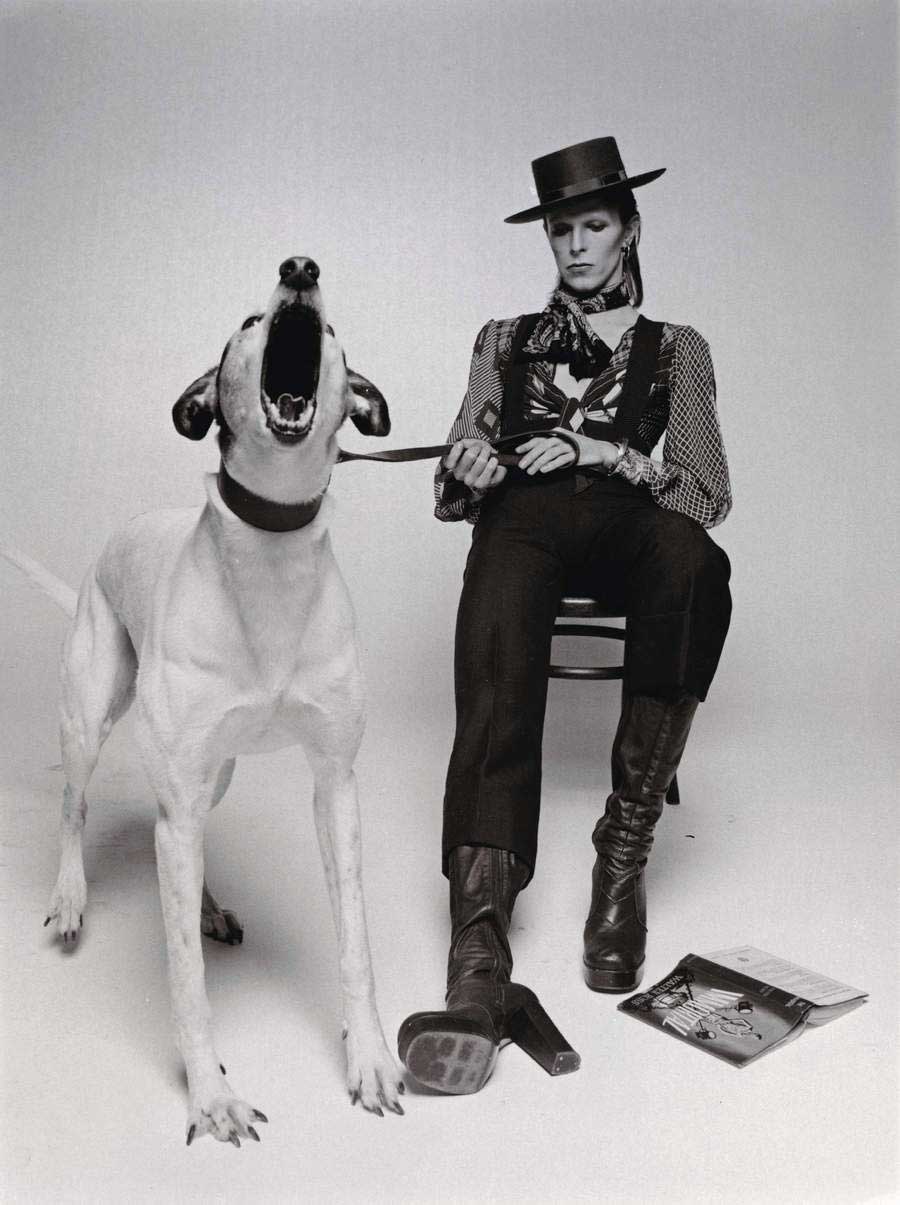

The faintly shocking, sci-fi cover artwork by the Belgian artist Guy Peellaert, featuring a picture of Bowie with his lower body transformed into that of a dog complete with genitalia (airbrushed from most versions at the time) became instantly iconic. Bowie got the idea after Mick Jagger told him that Peellaert was designing the sleeve of the forthcoming Stones album It’s Only Rock’N’Roll.

“I immediately rushed out and got Guy Peellaert to do my cover too,” Bowie admitted later. When It’s Only Rock’N’Roll was released several months after Diamond Dogs, everyone assumed the Stones had copied Bowie. “He [Jagger] never forgave me for that!” Bowie said.

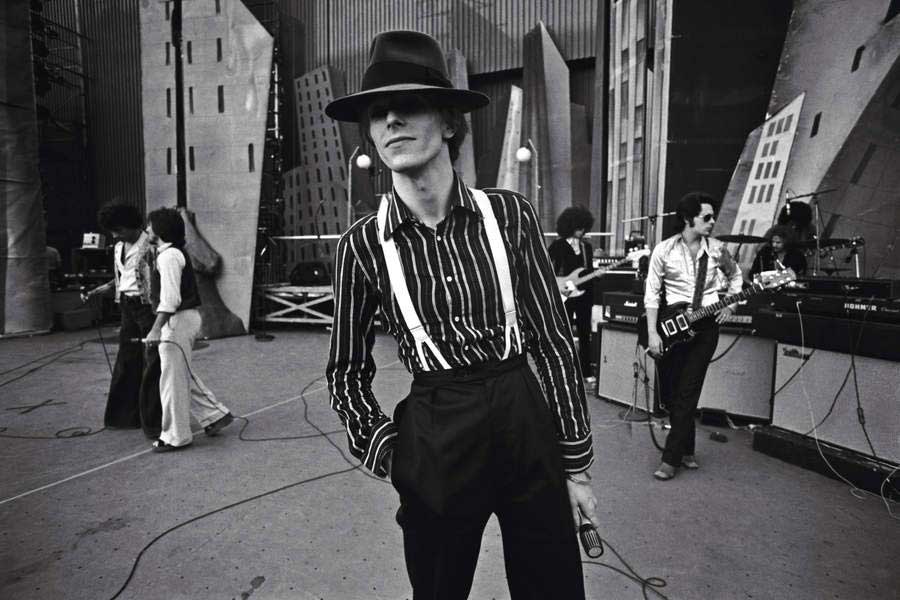

The spectacular and technically ambitious tour to promote Diamond Dogs set new standards for theatrical invention and sheer scale of endeavour. According to the Bowie chronicler Nicholas Pegg the stage set “was more elaborate than any previously attempted for a rock tour and cost an unprecedented $250,000… A giant backdrop depicted the nightmarish Hunger City skyline, tilted in jagged perspective. To either side stood two massive aluminium skyscrapers, linked by a moving bridge which would rise and fall during the show. The specialist props, run by hydraulic mechanisms and early forms of computer control, were to be built from scratch.”

The early reviews were delirious. The reviewer from Melody Maker described it as “a combination of contemporary music and theatre that is several years ahead of its time… a completely new concept in rock theatre – the most original spectacle in rock I have ever seen.”

According to Bowie: “It was truly the first real rock and roll theatrical show that made any sense.” But he nevertheless remembered the tour as “quite an unbelievable headache”.

At times, the sheer ambition of the staging threatened to outstrip the technical knowhow. With cranes and cherry-pickers and bits of staging flying around, there was little margin for error.

According to stage manager Nick Russiyan, “David was in great danger physically and could have gotten electrocuted or killed.” There was a disconnect too between the sophisticated musicianship of the new stage band – featuring guitarists Carlos Alomar and Earl Slick – and the rough edges of the original Diamond Dogs recording, played by Bowie himself.

“That album had a quality of obsession with what I wanted to get over,” Bowie later reflected. “They played it too well and with too much fluidity. So to me Diamond Dogs was never played well on stage, or at least never with the sensibility that the album had.”

Despite the positive reaction, the production was scaled back dramatically after the first leg and morphed into the so-called Soul Tour, with a set-list featuring material from Bowie’s forthcoming album Young Americans (released in 1975).

“I threw the set away and came back with a completely different show,” Bowie later recalled. “They were supposed to be selling the entire show on this spectacular set, and the kids would come and there was no set, no nothing, and there I was singing soul music.”

“Diamond Dogs was a weird period because everything that David had done up to that point suddenly exploded,” said guitarist Earl Slick. “It was like a nuclear explosion… Bowiemania… Then he decided to just abandon the whole thing. Diamond Dogs is probably one of the most iconic things he did in his entire career but… it [the tour] didn’t even make the WestCoast.”

“It was pretty obvious that David was taking coke,” recalled Jayne County, the American proto-punk glam-rocker who was signed to Bowie’s management firm MainMan at that time. “He became very skeletal in his appearance and began rattling off speeches that sounded meaningless to the rest of us… He began to get paranoid… accusing people of ripping him off and stealing his drugs.”

“Diamond Dogs scared me because I was mutating into something I just didn’t believe in any more, and the dreadful thing was, it was so easy,” Bowie said, looking back in 2008. “The Diamond Dogs period was just an extension of Aladdin Sane, which in itself was just an extrapolation of Ziggy Stardust.

“But by the time of Diamond Dogs that persona had started to feel claustrophobic, and I needed a change… Diamond Dogs was making me sick, both physically and creatively, and I was shifting into melodrama."