In the Conservatorium Hotel in Amsterdam, around the corner from the Van Gogh Museum, Britain’s greatest living artist is talking about his latest one-man show. Actually, it’s a two-man show: most of the landscape paintings in this exhibition are by David Hockney, but they’re juxtaposed with landscapes by one of his great artistic heroes: Vincent van Gogh.

“He’s one of the great, great draughtsmen of all time,”Hockney, fielding questions from a crowd of journalists, who’ve flown in from all around the world. “The drawings are fantastic – he could see space very clearly.” And the paintings are something else. “Van Gogh is telling us that there’s a marvellous world in your own back garden. You just have to look at it – really look. I think that’s his message. It’s thrilling if you really look.”

Hockney is wearing a natty flat cap and a lime green cardigan – he’s always been a stylish dresser. He seems cheerful and contented – he’s always been comfortable in his own skin. However he looks older and frailer than he did a few years ago, and he talks a lot more slowly. This should come as no surprise – he is 81, after all – but somehow it’s still a shock. With his boyish good looks, he was the Peter Pan of Pop Art. Even in late middle age, he seemed a lot younger than his years. Now he finally looks his age, but we should be thankful he’s still alive and still painting. If Van Gogh had lived as long as Hockney, he would have still been alive in the 1930s.

“I’ve been deeply influenced by Van Gogh – it’s very visible in this show,” he says. “Van Gogh, to me, is a contemporary artist. Any artist that speaks to you is a contemporary artist. Brueghel is a contemporary artist to me.” Another big influence in his life has been Van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo. “They’re marvellous,” he says. “If it had been 10 years later he might have been on the phone and the letters wouldn’t exist.”

Hockney’s first encounter with Van Gogh was back in 1955, when he was a student at Bradford School of Art. The art school arranged a trip to a Van Gogh exhibition in Manchester, and Hockney was blown away by the energy, the vitality, the joie de vivre of his paintings. “I was 16 years old and I’d just started at the art school,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘Well, he’s quite a rich artist, because he could use two whole tubes of blue to paint the sky’. Not even teachers at the art school could afford that!”

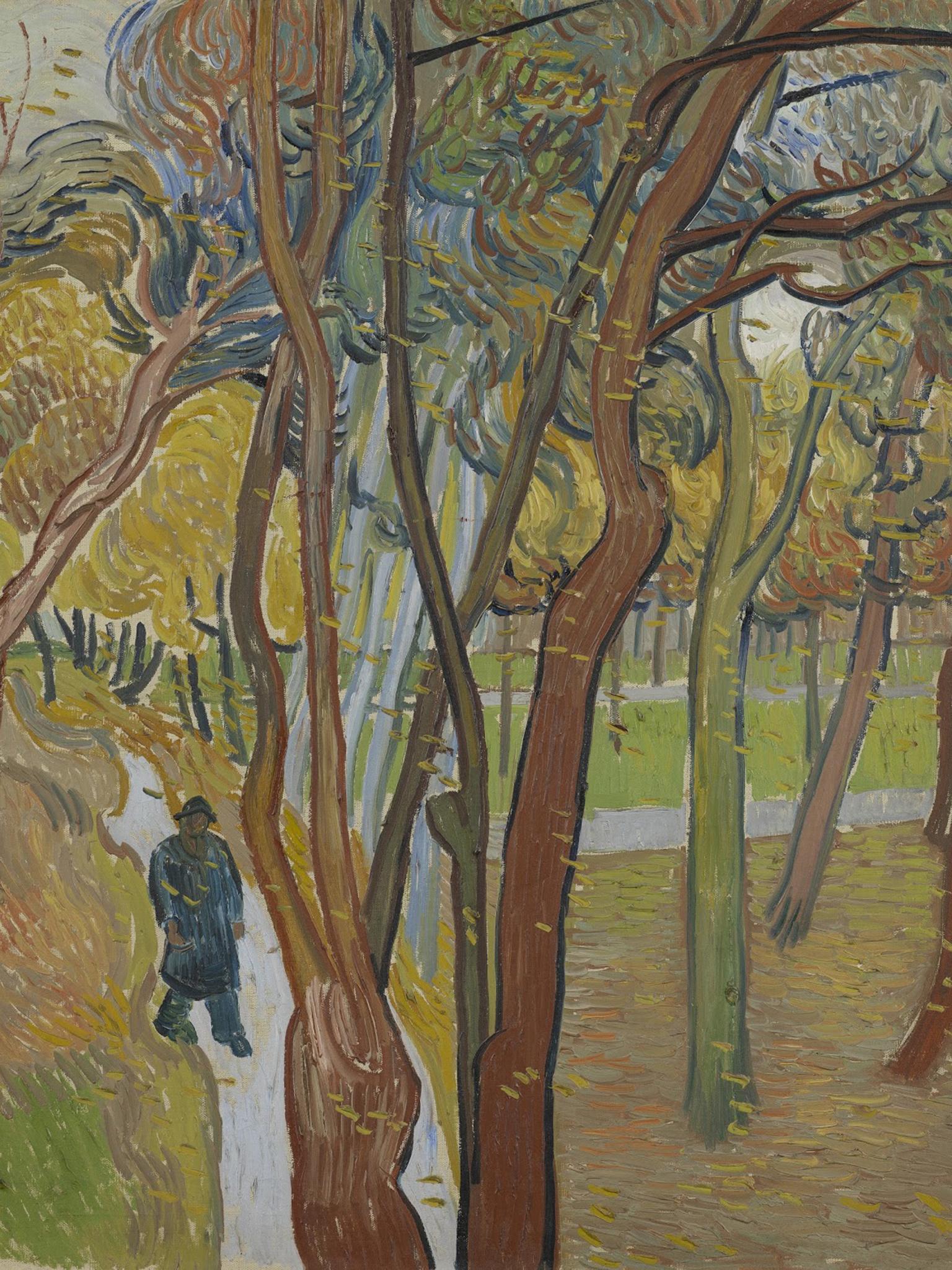

It was the colour that moved him most of all. “I’d never seen paintings like that before – at the art school everybody just painted grey pictures of Bradford. There was not much colour at all. At first I thought he’d probably exaggerated some colour, but now I don’t think so.” Sixty-four years later, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, which holds the world’s largest collection of Van Gogh’s work, has had the bright idea of juxtaposing a large array of Hockney’s Yorkshire landscape paintings with a smaller selection of Van Gogh’s landscapes, painted in the 1880s in the south of France. Hockney is flattered by this association. “Van Gogh is a terrific inspiration.”

Of course there are some similarities between Van Gogh’s woods and wheat fields and Hockney’s, but this show isn’t about narrow comparisons, of style or subject matter. It’s about their shared love of light. Above all, it’s about their lust for life. They’re both artists who adore the natural world, and paint it compulsively. “They’re just so joyful,” he says, of Van Gogh’s landscapes. You could say the same of his. Fittingly, the show is called The Joy of Nature.

As Hockney says, it’s a far better title than Dave and Vince. It’s ironic that such joyful paintings were made by a man who chose to kill himself, but that paradox is part of what makes Van Gogh so compelling. “He was joyful when he painted – I know that, because that’s what he loved.”

This exhibition also represents a kind of renaissance, for Hockney’s landscape paintings, like Van Gogh’s, were cut short by a tragic, self-inflicted death. In March 2013, one of Hockney’s assistants, Dominic Elliott, died from drinking toilet cleaner in Hockney’s home in Bridlington, the Yorkshire seaside town where Hockney had been living intermittently since the early Noughties. Hockney was entirely blameless, but he’d been asleep in the house when it happened, and the shock was immense. He sold the house and moved back to Los Angeles, his adopted home for the past 30 years. For several months, he was unable to paint at all.

In July 2013 Hockney sent a picture to his friend and curator Edith Devaney. It was a portrait of his close friend and studio manager, Jean-Pierre Goncalves de Lima, sitting in Hockney’s LA studio, his head buried in his hands. Straight away, Devaney spotted the similarity with Van Gogh’s Old Man in Sorrow. This wasn’t just a portrait, Hockney told her – it was also a sort of self-portrait.

This portrait led to many more, and the result was his 2016 exhibition, 82 Portraits and One Still Life, at London’s Royal Academy, curated by Devaney. After the trauma of Elliot’s sudden death, Van Gogh helped to bring Hockney back into painting. And now Van Gogh has brought his Yorkshire landscapes, cruelly curtailed by that tragic accident, back to life.

The selection was mainly made by the Van Gogh Museum, but Hockney did ask them to include The Road to York through Sledmere, which he painted a decade earlier, as homage to his friend Jonathan Silver. Silver revived Salts Mill in Saltaire, Yorkshire, as a cultural centre (and as a museum of Hockney’s work). He died of pancreatic cancer in 1997, aged just 48. When Silver was very ill, Hockney spent a lot of time with him.

He asked Silver if there was anything he could do for him. Silver asked him to paint east Yorkshire – a subtler landscape than West Yorkshire, where Hockney was born and raised. “That picture was painted when Jonathan Silver was dying, and I was driving constantly from Bridlington to Saltaire, and I always went through Sledmere,” remembers Hockney. “It’s always been on my wall.”

English landscape paintings are often muted, a blur of browns and greys. Hockney’s English landscapes are glowing – bursting with bright colours and brilliant light. “I’d lived in California for 30 years. It’s bound to have an effect. But I don’t think I exaggerated the colour that much – no, I don’t think so. I think it’s there, but you have to look – hard. Colour is a very fugitive thing.”

As he says, we all see colour differently. Some people see it more intensely. Hockney’s intense vision makes us look closer and the world look brighter. “When you’re looking at the world, there’s so much to see.”

David Hockney was born in Bradford in 1937, the fourth of five children. During the war his father Kenneth was a conscientious objector, which meant that when he lost his job, as a clerk, he wasn’t eligible for national assistance. He subsequently scratched a living renovating old prams. David drew from an early age, in chalk on the kitchen floor and in pencil in his brothers’ comics.

In 1947 he won a scholarship to Bradford Grammar School. He didn’t shine at school, which was just as well. If he’d been top of the class his teachers might have pushed him into a more respectable occupation. “He should realise that ability in and enthusiasm for art alone is not enough to make a career for him,” wrote his teacher on his school report.

Fortunately for Hockney, and the rest of us, he paid no attention to his teachers. He went to Bradford College of Art, which gave him a solid foundation in skills like life drawing, then on to the Royal College of Art, in London, where he found his voice. He came out as gay – a brave move in an era when homosexuality was still illegal – and his work blossomed. He made his first visit to America, and returned with his hair dyed blonde, after seeing a TV ad for Clairol which claimed that “blondes have more fun”.

By the time Hockney left the Royal College he was already represented by a Bond Street gallery. He moved into a two-room flat in London’s Notting Hill, still a rundown area back then. He slept in one room and used the other room as his studio. His immense talent was bolstered by his insatiable appetite for hard work. GET UP AND WORK IMMEDIATELY was painted in big block capitals on the chest of drawers at the foot of his bed.

His first solo show in 1963 earned him enough money to spend a year in America. As he told his friend Henry Geldzahler, he never felt lonely over there. He spent some time in New York but he was drawn to Los Angeles, where he’s lived, off and on, ever since.

“Southern California has a marvellous clarity in the light. That’s why Hollywood is there. I always loved the place. I never got bored of it.” The sun-drenched pictures he painted there would have been inconceivable in Britain. “In a cold place like Bradford you hardly see anybody without their clothes on,” he once remarked.

Then as now, LA is commonly derided by snobbish Brits (and New Yorkers) as a spiritual desert, devoid of culture, but Hockney saw a vivid, lively cityscape that no one else had painted, a city with “the only architecture in the world that makes you smile”. He took to calling himself an “English Los Angeleno”. He vowed to become the “Pirinesi of LA”.

His LA paintings made his name, in Britain and America, particularly his swimming pool pictures like A Bigger Splash and Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), which last year became the most expensive painting by a living artist when it sold at Christie’s in New York for $90m (£68m).

“The auction prices for my work have nothing to do with me – I ignore it,” he says, emphatically. “I think people have forgotten Oscar Wilde’s remark, ‘The only person who likes all kinds of art is an auctioneer’.”

He’s worked in all kinds of media, from film and photography to set design. He’s embraced every new innovation, from fax machines to smartphones. His iPad paintings were groundbreaking, proving that this new medium could be a new way to make great art.

“The first things I did were lots of sunrises from a window, and I realised that with the iPad I could draw without moving from my bed. I didn’t have to get up to get water, or a brush, or pencils, and I could draw in the dark, because of the back light, so I started drawing just before the dawn.” He painted dozens of pictures of the sun rising, on his iPad, through the same bedroom window. “Every day was different, different colours. No two sunrises are the same.”

Yet despite his love of hi-tech, he’ll always be remembered as a painter, and a traditional painter at that. “Modern art generally ignores skills and crafts,” he once said, in an interview with Art Monthly. When abstract art was all the rage he flew the flag for figuration. When conceptual art was all the rage he flew the flag for fine art.

“There’s a lot of the boring old northern art schoolmaster in what he says about representation versus abstraction,” wrote Tim Hilton, in The Guardian. But as a new generation of artists rediscover draughtsmanship, it seems Hockney has been proved right.

Despite his conventional views on art, he’s no reactionary fuddy-duddy. He was a tireless advocate for gay rights, long before such causes became chic. His friend Henry Geldzahler once wrote down a list of his faults and failings: stubborn; hard of hearing; unintentionally rude; suffers fools gladly; generous to a fault. It’s notable that several of these faults are actually virtues.

It’s hard to find an artist who’s so universally admired. And after all these years, his hunger for experience remains. “On Saturday I’m going off to Normandy to paint the arrival of spring,” he says. “I can’t think of anything better than watching the spring happen in Normandy in 2019.”

Hockney – Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature is at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam (vangoghmuseum.nl) until 26 May