Devastating wildfires across the world have made front-page news in recent times, from the current blazes in the Amazon, to last year’s deadly fires in Greece, to the widespread property destruction in Canada three years ago. One place you might not expect to be burning, however, is the Arctic. Yet at the time of writing, millions of hectares of land in the Arctic were ablaze.

Fire is a natural part of the ecology of the vast boreal forests that girdle Earth in northern latitudes. But the amount of vegetation that has been on fire across Alaska, Canada and Russia since June is highly unusual. Even Greenland, four-fifths of which is covered in ice, has seen fires. The impacts on human health and the environment are coming into focus – and they are worrying. Is there anything we can do?

Brazil’s space agency has reported a record high of more than 75,000 fires in the Amazon this year. And 2019 has seen other striking fires around the world, including in places not usually known for them, such as Britain. In Indonesia, where fires are often started to clear areas for oil-palm plantations, the fire season may prove to be as bad as that of 2015, when blazes there created a plume of smoke that extended halfway around the planet. A surprising number of crop fires have hit the Netherlands, Germany and Luxembourg, says Cathelijne Stoof of Wageningen University in the Netherlands.

You would be forgiven for thinking that fires are on the rise globally. In fact, the evidence doesn’t bear that out. For example, a 2017 study led by Niels Andela, at Nasa, used satellite images to show that the amount of land being burned worldwide has actually decreased in recent decades. This is probably because of the way we are managing forests to reduce the risk of fire.

Surprising as it may seem, this year isn’t that special when it comes to fire, either, globally speaking. The European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) says that some 3,500 megatonnes of carbon dioxide were emitted from wildfires in the first half of this year. At a global level, that makes 2019 distinctly middling compared with the past 16 years.

The fires in the north, however, are exceptional. “This year has been unprecedented for wildfires in the Arctic,” says Carly Phillips, at the Union of Concerned Scientists and Woods Hole Research Centre, in Massachusetts, the United States. About 173 megatonnes of CO2 have been emitted from Arctic fires so far this year, which is a record. Russia has been hit hardest, with more than 13 million hectares affected and smoke hazes reported in cities.

So why the surge in Arctic fires? The region is effectively stuffed with fuel: huge swathes of forest and peat. Most of this doesn’t normally burn because it is cold and wet. But this year, temperature changes have made it warm and dry enough for blazes. “The north is a big tinder box, but it’s been limited from burning by the climate,” says Merritt Turetsky, an ecosystem ecologist at the University of Guelph in Canada. “If you remove those climatic constraints, all those fuels are ready to go.”

Climate change could also be contributing to the lightning strikes that usually ignite the fires. More lightning is linked to rising surface temperatures. “Hot weather is making the Arctic more thunderstormy than normal,” says Rod Taylor of the World Resources Institute in Washington, in the US.

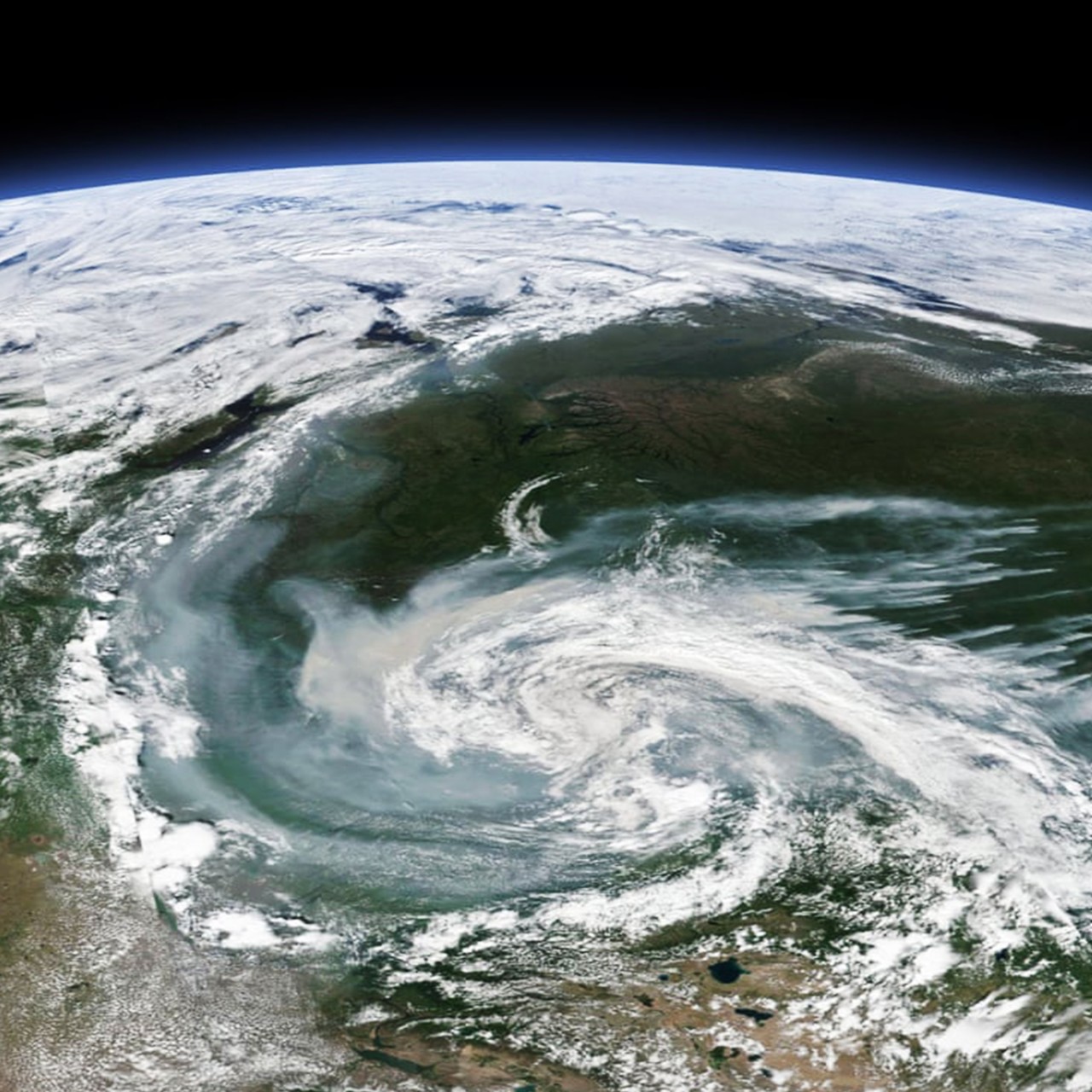

Most of the fires are in remote regions, but that doesn’t mean people are escaping the effects. “What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. Pollution can carry thousands of miles away,” says Elizabeth Hoy, at Nasa. The agency has tracked smoke from the fires in Siberia reaching the US and Canada. That pollution can combine with a city’s local fumes to turn air quality from average to poor, potentially causing respiratory problems for young, old and other vulnerable people.

The health costs aren’t just physical. Turetsky says that in Yellowknife, the capital of the Northwest Territories in Canada, doctors have reported increasing rates of hospital admissions for post-traumatic stress disorder during and following wildfires. At a workshop she ran in the city, many people reported what they called eco anxiety. “A lot of these people didn’t experience the fires directly, but they know it’s going to come back,” says Turetsky.

The effect on the climate could be more serious still. The problem isn’t simply that fires release a lot of CO2. This will exacerbate global warming, and Arctic wildfires have released about the same amount of CO2 this year as the Netherlands does in a year.

“For me what is far more insidious is the long-term climate impact,” says Phillips. Her worry is the prospect of a harmful positive feedback loop. Fires burn off vegetation, stripping away an insulating layer that helps maintain permafrost – ground that is normally frozen. This makes it more likely that the permafrost could thaw and release even more CO2. Permafrost thaws discharge not just CO2, but also the more powerful greenhouse gas, methane.

The potential positive feedback doesn’t end there. Researchers at CAMS have already used satellites to track soot from this year’s northern Russia fires. Some landed on ice in Greenland. That matters because studies have shown that soot can alter the reflectivity of ice, making it absorb more of the sun’s energy and heat up.

The remote nature and sheer scale of the Arctic means there isn’t a lot that firefighters can do about these fires. Russia had to send in the army, planes and helicopters to tackle flames in some areas. “Large-scale intervention is very costly and not very effective for large and remote fires,” says Cristina Santín, a biologist at Swansea University in Britain.

Russian authorities have tried seeding clouds to induce rain. The idea is that planes spray chemicals such as silver iodide in an effort to enhance the rate of ice crystal formation in the atmosphere, producing more clouds, but there is no evidence this is effective.

Today, firefighters’ priority is to protect life and property. Turetsky says that could in future be extended to protecting rich stores of carbon in the Arctic. “It might be governments come together to protect certain areas where we understand where the old carbon is,” she says. The other thing we can do is to reduce CO2 emissions.

In the future, hotter, drier conditions in the Arctic will set the stage for more blazes. A recent report on land use by the United Nation’s climate-science panel warned as much. Stephen Pyne, who studies the history of fire at Arizona State University, in the US, says we are entering the “age of the pyrocene”.

One crumb of comfort is that the feedback loop can’t continue forever. A forest can burn only once. And smoke from northern fires has a modest cooling effect, reflecting some of the sun’s energy. In the meantime, however, the Arctic is still on fire.

New Scientist

.png?w=600)