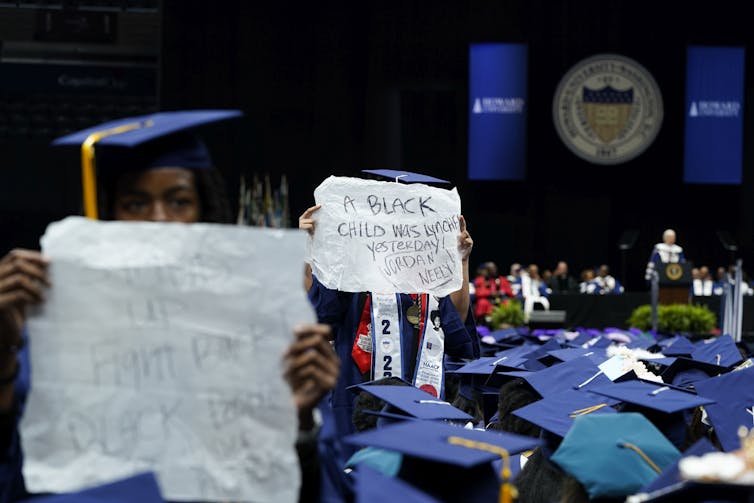

A former United States Marine was recently charged with second-degree manslaughter for fatally choking a 30-year-old Black man, Jordan Neely, on a New York subway train.

A GiveSendGo crowdfunding campaign has raised over $2.8 million from 57,000 donations for Daniel Penny’s legal expenses. It’s the second largest fundraiser on that platform.

While many people on the left have expressed dismay at the success of this fundraiser, GiveSendGo isn’t necessarily wrong to host it.

What’s more objectionable about this campaign isn’t so much that it helps someone defend himself in court but what it demonstrates about the larger, and highly inequitable, enterprise of crowdfunding itself.

Violent crime ban

Penny’s fundraiser was likely created on GiveSendGo rather than the much larger and better known GoFundMe website because GoFundMe has a policy against allowing fundraisers for the legal defence of people accused of violent crimes.

After Illinois teenager Kyle Rittenhouse was charged with the death of two Black Lives Matter protesters in 2020, GoFundMe announced a policy banning campaigns for the “legal defence of alleged financial and violent crimes.”

This has made GiveSendGo a home for right-wing legal causes, including legal defence funds for Rittenhouse, police officers accused of homicide, Jan. 6 rioters, Canada’s so-called Freedom Convoy activists and, most recently, Penny.

In many cases these fundraisers have been enormously successful, raising hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars.

Read more: Is GoFundMe violating its own terms of service on the 'freedom convoy?'

There are many compelling reasons to condemn the kinds of crowdfunding campaigns that GiveSendGo often hosts. Its lax moderation policies have made it home to a wide range of activities and organizations that spread hate and bigotry, harming specific groups.

But helping people accused of violent crimes to defend themselves in court is a different matter. Legal defence and due process in the courts are a basic civil right. While many of us find Penny’s actions horrific and welcome the charge of manslaughter against him, it’s his right to defend himself in court and to access legal counsel to do so.

Unfair advantage

Nonetheless, Penny’s fundraiser shows crowdfunding is a wildly unfair way of securing this and other rights.

It was initiated by his legal team even before charges were laid against him. He has benefited from the politicization of his actions and wide support on the political right, including calls to support the fundraiser from politicians like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and Republican congressman Matt Gaetz.

After Penny was charged with manslaughter, funds began pouring into the 24-year-old’s campaign, helped by exposure on mainstream and social media. As a result, Penny will have the finest legal defence money can buy, likely with ample money left over.

This isn’t the case for the vast majority of people accused of crimes — violent or otherwise — who are equally deserving of effective legal counsel.

Most crowdfunding campaigns fall well short of their goals. White beneficiaries generally fare better than Black and other racialized minorities, and people in relatively wealthy and well-educated communities raise more money than those in less affluent areas.

All campaigners rely on networks of donors for support. People with more privileged networks can expect better outcomes than people in positions of greater relative need.

Campaigns with no support

What this means is that crowdfunding isn’t a fair means for people accused of violent crimes to pay for their legal defence.

For every Daniel Penny or Kyle Rittenhouse, there are thousands of campaigns that get little or no public support.

Perhaps their alleged crimes are abhorrent and people would have no interest in financially supporting those accused of them. But the bottom line is that some of these people are innocent of the crimes they’re accused of and, regardless, everyone is deserving of an effective legal defence.

In the United States and most other democracies, all people in principle have access to public defenders and their basic right to legal due process is secured in this way. But the reality is that public defenders are often under-resourced, overburdened, and struggle to provide their clients with effective counsel even with their best efforts.

In other cases, these defenders fail outright in their duties to their clients.

That means a defendant with a multi-million-dollar legal fund is in a wildly different position than the much larger mass of people navigating public defender systems.

Reputational damage

GoFundMe’s decision to ban campaigns for the legal defence of people accused of violent crimes was likely driven by reputational concerns rather than principle.

It’s understandable that a company that brands itself as the most helpful place in the world doesn’t want to invite criticism for hosting high-profile campaigns for police officers who killed Black Americans during arrests, political insurrectionists and people who shoot racial justice protesters.

We can question the priorities and values of donors who enthusiastically support primarily white defendants accused of violence against protesters and people experiencing mental health crises while ignoring others in need.

But helping people secure due process in the courts is a noble goal, as are crowdfunding campaigns that help pay for medical care, housing and education.

The problem is that crowdfunding operates largely as a popularity contest, distributing help in deeply inequitable ways. That, among other things, is what Penny’s campaign reveals: Leaving it up to the public to pick who should have access to basic rights leads to deeply unfair outcomes.

If people on the left and right can agree that a legal defence is something everyone deserves, then we should also agree that crowdfunding isn’t the way to secure this right.

Jeremy Snyder receives funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the Greenwall Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.