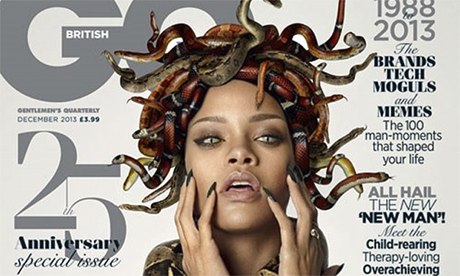

The artist Jim Starr has accused Damien Hirst of plagiarism. Hirst has put a picture of Rihanna as the snaked-headed monster Medusa on the cover of GQ. Hey, wait a minute, says Starr – I was the first to portray sexy snake-haired women.

It's always fun to take a pop at Hirst, but hang on. Haven't I seen images of Medusa before that far outdate Hirst and Starr? I suspect plagiarism claims are redundant when artists have been depicting something for more than 2,500 years.

Medusa was, in ancient Greek myth, one of the Gorgons, three monstrous sisters with magical powers. She was so malevolent that just looking at her turned people to stone. How can you kill such a being? The Greek hero Perseus used a shiny shield as a mirror so he only saw a reflection as he sliced off her serpent-swathed head and stuffed it in a sack. Later, at his wedding, he fought off a violent mob by unveiling the head and turning his enemies to stone.

This is the moment Luca Giordano chose to show in the 1680s in a baroque painting whose fascination lies in the way flesh turns to stone before our eyes. As he holds forth the head of Medusa at the heart of this spectacular picture in London's National Gallery, Perseus averts his gaze.

Artists had already been imagining Medusa for millennia when this powerful scene was painted. An archaic-period Greek bowl in the British Museum, from 600BC or earlier, has an image of Medusa glaring outwards, as if about to turn you to stone: it must have been quite a talking point when the bowl was emptied of olives at a banquet, only to reveal this hideous face.

Medusa was popular right through the ancient Greek world, appearing on everything from temples to pots. Yet the most potent images of her were to be painted and sculpted in the 17th century, when this bizarre being became an icon of baroque art.

For that we probably have to thank Caravaggio, who created an unforgettable "portrait" of Medusa on a painted shield. Today it's in the Uffizi. Caravaggio's Medusa is one of the most incisive images of myth ever created. This is because it takes a legend and makes it all too real – this is a viscerally, uncannily alive Medusa.

In the wake of Caravaggio, great artists of the 17th century all wanted to have a pop at making Medusa real. Bernini made her look like an ordinary woman who happens to have snakes for hair. Rubens depicted her severed head on the ground, a mass of reptilian horror.

So the charge against Hirst is not plagiarism – it is sheer artistic ordinariness. Neither he nor Starr have added anything original to the image of Medusa. The GQ cover is as insipid as some late Victorian mythic erotica. Compared with the great Medusas of the classical and baroque ages, Rihanna with snaky hair is just plain dull.

It goes to show that Caravaggio could take Hirst in a fight, any day.