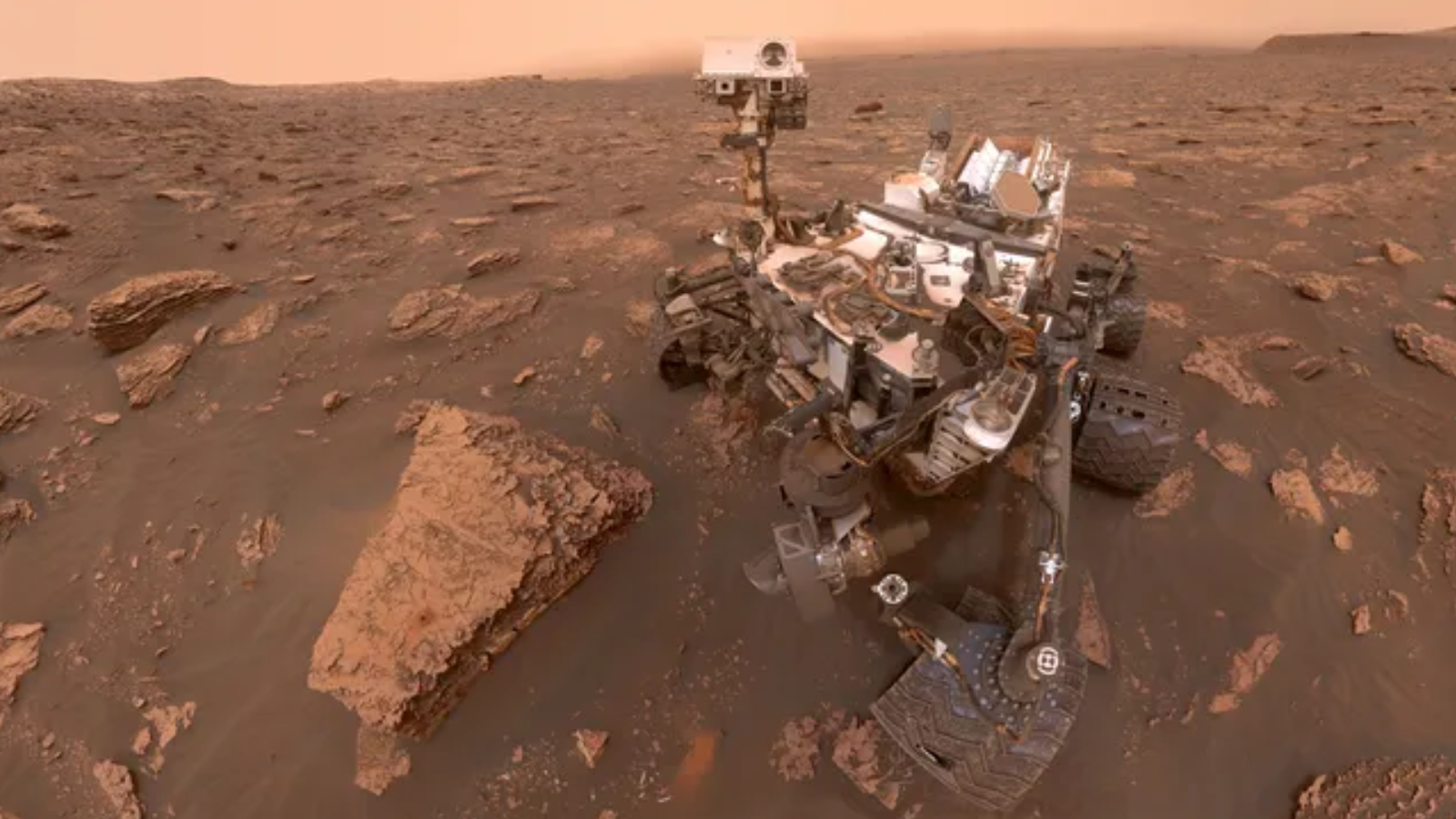

Since 2012, NASA's Curiosity rover has repeatedly detected methane on Mars, specifically near its landing site inside the 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater.

But that Mars methane is behaving erratically. It only appears at night, it fluctuates seasonally and it spikes unexpectedly to levels 40 times higher than usual. To make things more puzzling, the gas isn't present in appreciable amounts high in the Martian atmosphere, and it hasn't been detected near the surface in other Red Planet locales. So what's going on at Gale Crater?

A group of NASA researchers led by planetary scientist Alexander Pavlov may now have at least a partial answer. The team suggests the Mars methane is trapped beneath a crust of solidified salt within the regolith at Gale. Warm daytime temperatures could weaken the crust, allowing methane to slip out at night. And the weight of a heavy rover driving over the crust could crack the crust, too, allowing methane to burst out in a concentrated puff. (Yes, it's akin to burping a baby.)

Related: NASA's Mars rover Curiosity: The ultimate guide

The researchers tested their hypothesis here on Earth, using a simulated Martian regolith; a salt called perchlorate, which exists widely on Mars; and neon as an analog for methane. Their tests, performed inside a Mars simulation chamber at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, showed that a salt crust could form under certain conditions, trapping methane beneath it.

While a layer of solidified salt might explain the irregular behavior of Martian methane, scientists still don't know why methane even exists on Mars in the first place. On Earth, methane is primarily produced by living organisms — but we still haven't found signs of life on Mars.

And, to be clear, methane is not a surefire sign of life; the gas can be produced by geological processes as well.

"It's a story with a lot of plot twists," Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity's project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, said in a statement. "Some of the methane work will have to be left to future surface spacecraft that are more focused on answering these specific questions."

A paper on the team's research was published on March 9, 2024, in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

.jpg?w=600)