On November 18, 1978, more than 900 Americans died in the jungle in Guyana after drinking a cyanide-laced fruit drink at the behest of their leader, the Reverend Jim Jones. It is one of the largest mass death events in American history, and has become so ingrained in popular culture that “drinking the Kool-Aid” has become an idiom for belief in any dangerous ideology. In a new documentary about that fateful day, Cult Massacre: One Day in Jonestown, Jones’s son Stephan Jones argues that the phrase shifts the blame away from where it truly belongs. “That night was murder,” he says.

The new three-part documentary, from director Marian Mohamed, explores the events that led up to that horrendous day in November through the eyes of some of those who survived. She speaks to Stephan, who was in Guyana’s capital, Georgetown, when the killing began. She also interviews Yulanda Williams, who was a follower of Jones’s group The Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ, and former Congresswoman Jackie Speier who accompanied her then-boss Leo Ryan to investigate Jonestown and survived five gunshot wounds when Ryan was assassinated as they tried to leave.

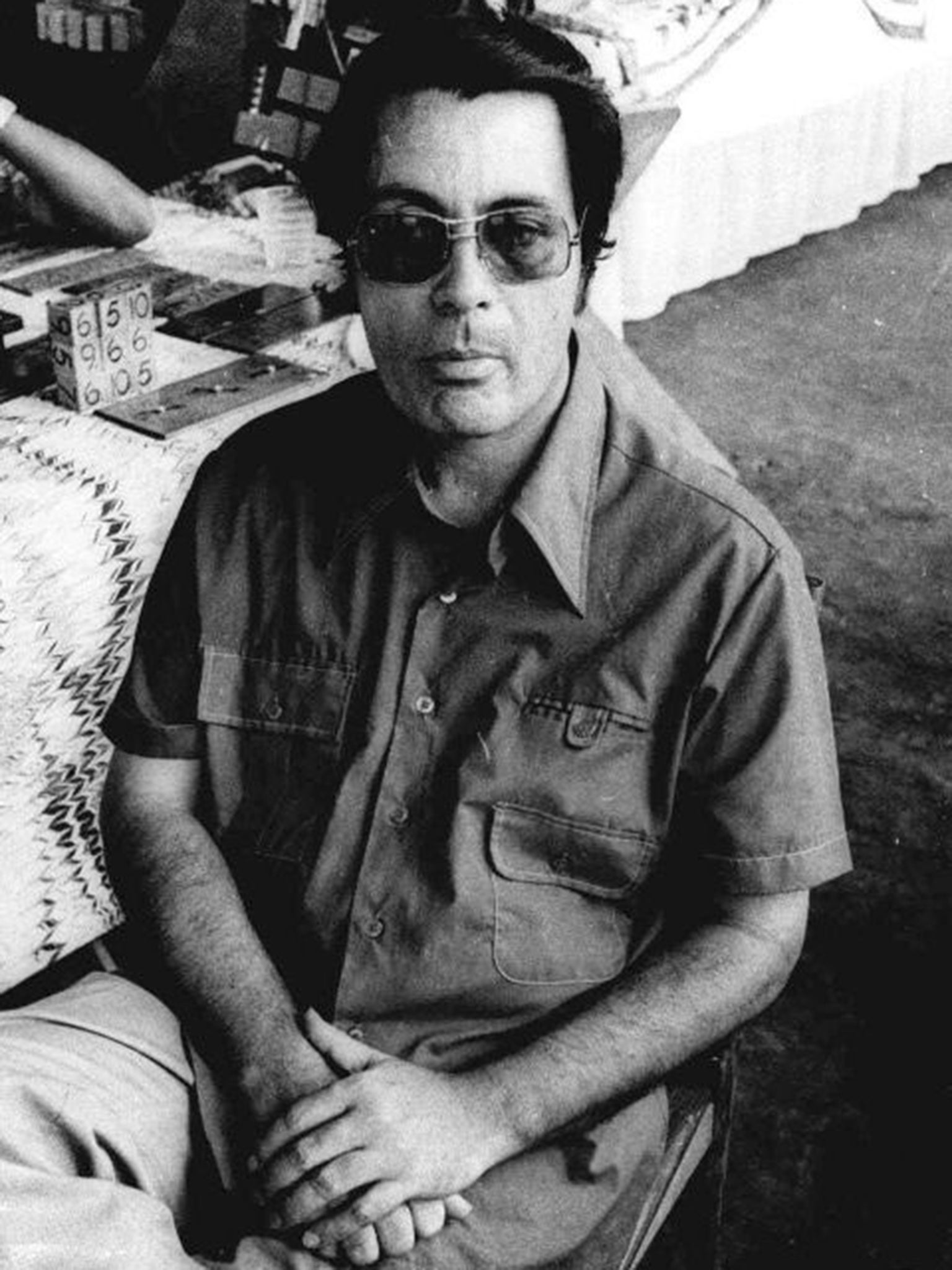

It is Stephan who offers the most insight into why his father was able to command such obedience in his followers. “Folks have really not done a good job of showing what was attractive about my father,” he says in the documentary. “I’m not here to protect his memory at all. But so what you see in the media about my father, one who didn’t experience the Temple, can’t help but think, why would anyone follow that guy? There must have been something wrong with these people from the start.”

As the film shows, the roots of the tragedy date back to 1955 when Jones first formed The Peoples Temple in Indianapolis, Indiana. He preached a message of social justice and racial integration that was radical for the time. When he adopted a Black child and gave him his own name, Jim Jones Jr became the first African-American child adopted by a Caucasian family in the state of Indiana. According to one contemporary newspaper, Jones offered his mainly Black congregation “opportunities in social justice activism” that were not available elsewhere. The Temple fed pensioners, taught students, and took bus trips to spread the word.

Their integrationist message caused friction in Indiana, however, and in 1965 Jones moved his church to California. By the 1970s they had found a new base in San Francisco, where Temple members campaigned to help get Democrat George Moscone elected as San Francisco mayor. In 1976, Moscone returned the favor by appointing Jones to the San Francisco Housing Commission. As Jones’s political influence grew, so did public scrutiny of the increasingly unhinged and prescription drug-addicted leader.

Jones had a solution: Jonestown. He envisioned the new town in the jungles of Guyana as a “rainbow community” and a “socialist paradise” where his followers could live freely away from the prying eyes of the media and the US government. In 2010, Jim Jones Jr, who was 17 when he moved to Jonestown, told Oprah Winfrey that he really believed the isolated township would be a utopia. “We had an organisational structure,” he said. “An agricultural team, education projects, the infirmary. It was a whole community.”

But that sort of revolutionary idealism soon gave way to strict control as Jones became more paranoid and cruel. For example, anyone complaining about the maggots in their rice risked a beating because moaning about the food made you a traitor in league with the CIA. Escape from the camp complex was impossible. Armed Temple security guards patrolled the exit trails. A watchtower was erected. Those who did try to escape were taken to the “Extra Care Unit”.

Alarms were raised back at home. In November 1978, California Democrat Congressman Leo Ryan flew to Guyana to investigate complaints he was hearing about the Temple. He arrived on the 17th with a delegation of news reporters and representatives of the Concerned Relatives, a group formed by US-based defectors and family members of Jonestown residents.

When the delegation left the following afternoon, they took with them 16 Jonestown residents who had implored the congressman to take them with him. They got as far as the Port Kaituma airstrip, six miles from Jonestown, before they were ambushed and shot at. Ryan was killed, shot more than 20 times, and his aide Jackie Speier survived being shot five times herself.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Back at Jonestown, Jones gathered his people together in the pavilion. “How very much I loved you,” he told them. “How very much I tried to give you a good life.” Then he served them the drink that would kill them. Although later the cult would become associated with “drinking the Kool-Aid”, in truth they preferred a cheaper alternative – Flavor Aid – which was used to mask the bitter taste of cyanide, mixed with a dash of Valium. Jones persuaded his disciples to poison their children first, reasoning that once they had seen their kids die they would have nothing left to live for. The “deranged preacher”, as the press would call him, wanted to create a glorious sacrifice, a defiant act of “revolutionary suicide” that he believed would echo through history.

By the time journalists and investigators returned to the site by helicopter, the stench of death hit them while they were still at 300ft. From that height, the piles of dead bodies looked to one reporter like “a garbage dump, where someone had dumped a lot of rag dolls”, dressed in red, green and blue: “bright, happy colors”. On the ground, as reporters clutched handkerchiefs to shield their noses from the smell, they could see how the bright, happy clothes were all that was holding many of the corpses together. They were decomposing in the jungle heat.

There were only a handful of survivors, including Jim Jones Jr and Stephan Jones who were attending a basketball game that day in Georgetown. Several of those who did live to see another day share their stories in Mohamed’s new documentary. It offers an empathetic view of what drew so many people there to die in the jungle. “They weren’t loonies. They weren’t crazies,” Mohamed told Time. “These were people that wanted to be part of something.”

Cult Massacre: One Day in Jonestown is available to stream on Hulu in the US and on Disney+ in the UK