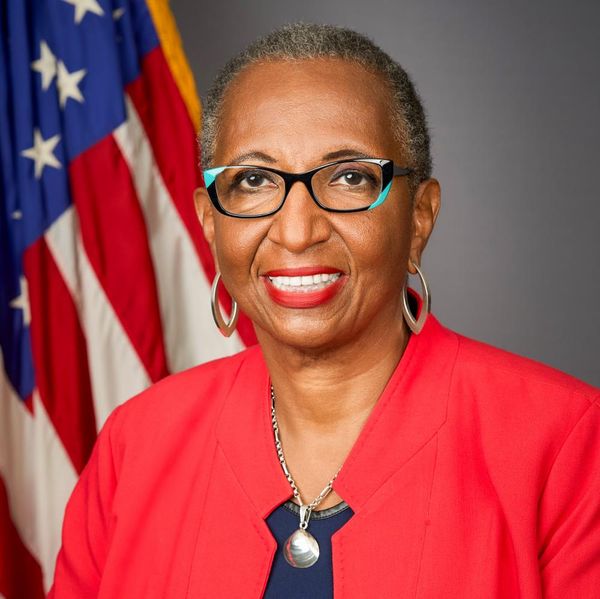

Tara Morelos has been a food co-op member for most of her life, and has never seen the model more imperilled.

Morelos is the chair of Alfalfa House, a food co-op established in 1988 that closed its doors this year due to dwindling membership and skyrocketing operational costs.

“I feel saddened by that loss of community,” Morelos says with a sigh.

“I feel tired of banging on about it, but I’ve invested my life into this … I am eternally committed to the principle of it.”

Once a fixture of inner-western Sydney, Alfalfa House sold affordable, organic fresh produce and dry goods. The shop front held its last trading day in April.

Since then, the co-op has been searching for a new location with hopes to “reinvent” itself after membership fell from more than 1,200 before Covid to less than 450 this year.

That dramatic drop was near fatal for the food co-operative, because the model depends on membership to operate. “It ended up knocking the stuffing out of us,” Morelos says.

“[Members] literally walked away, some due to the restrictions implemented during the lockdowns. And in our case, we rely quite heavily on memberships and annual subscription fees to keep going.”

“The co-op itself continues as an entity, but we’ve been struggling to keep our members engaged.”

Alfalfa once offered three membership tiers – a passionate tier at $50 a year, a regular tier at $30 a year and a concession tier at $20 a year.

Members had access to a 10% discount when the shop front was open, and retain a say in how the co-op is run, via a voting system.

The drop in members was matched by a drop in volunteers, which made the everyday operational work of running the co-op very difficult.

“There was this perception that it was a little, expensive club. And that affected us, particularly during a cost-of-living crisis,” Morelos says. But this perception was not accurate. The organisation carried out a “massive revise” of their costings that resulted in prices comparable to major supermarkets.

Alfalfa House’s challenges are not unique. Food co-ops across the countryare struggling with declining membership, reduced spending and rising rental costs – all set against the backdrop of a cost-of-living crisis.

These issues led Sandra Clark to help set up the Grocer Co-Op, a union of sorts for food co-ops, where organisations can join to share information and work together to preserve the co-op model.

Clark says most of the co-ops that have joined her umbrella organisation are “struggling at the moment”.

“We are trying to prevent closure,” she says. Many co-ops share similar organisational and operational structures, which makes knowledge-sharing particularly helpful. “So they don’t fall into the same pitfalls others have.”

Clark says increases in rent across the country have had an adverse effect on food co-ops. Although such organisations are not-for-profit entities, they often have to apply for commercial leases. “Most food co-ops … may not be able to pay competitive commercial rent. It has caused some to close down, while others are looking to move to cheaper rental locations.”

Amid increased profits posted by supermarket giants Coles and Woolworths, who control two-thirds of the market, Clark says it is important consumers are given an ethical, local choice.

“We don’t have the buying capacity or ability to go back to suppliers and tell them, ‘We’re paying you less money and discounting the product’. That is something the supermarkets do, and it makes it very difficult for us to compete with them.

She says the co-op model has reached a turning point and needs to adapt to the current demands of Australian consumers.

“We will either see the demise of food co-ops, or we will possibly see a change in the way that they are structured to be viable.”

Sam Byrne, secretary of the Co-op Federation, which advocates on behalf of the co-operative model across the country, says food co-ops need to be “nimble and agile” to survive.

“As households are being squeezed … it’s natural they’d look for the cheapest options.”

But offering a viable alternative to large supermarkets is baked into the co-op model. “It’s why they exist,” Byrne says. “To challenge that ... producers love supplying food to co-ops because they get a fair price and are paid quickly.”

“But it ultimately comes down to that economic squeeze we have at the moment, it’s a tough time for any business.”

Byrne was an Alfalfa House customer for years, and says the closure was devastating.

“I’ve been a member for a long time, Alfalfa was my first food co-op, my children have grown up shopping there.”

“But we are hopeful of a revival, and are looking forward to seeing Alfalfa 2.0.”