At 3:27 p.m. on Nov. 28, 2022, Bank of America began processing an account application submitted online by a criminal using a false identity. Two minutes later, it asked the imaginary person to confirm his email address. At 4:02 p.m., the bank emailed the criminal. “Great news!” the email declared — the new account was ready for use.

No one from Bank of America saw or spoke to the client before opening the account to confirm he was who he claimed to be. And Bank of America, which did not return calls seeking comment, isn’t the only snookered bank.

Stolen and fictitious identities have been used to open thousands of sham accounts at almost every major banking institution in the United States. These criminal accounts, known as drop accounts, facilitate a wide range of fraud because they allow even the most unsophisticated thief to launder criminal proceeds and convert it to cash without detection.

Street gangs, organized crime syndicates and rag tag groups of scammers use drop accounts to stash billions of dollars stolen from individuals, businesses and even the federal government, a joint investigation by the Evidence-Based Cybersecurity Research Group at Georgia State University and The Conversation has found.

Through Internet transactions alone, swindles typically facilitated by drop accounts cost individuals and businesses almost $4.8 billion last year, a jump of about 60% from comparable fraud losses of more than $3 billion in 2020, according to the FBI.

The number of drop accounts has exploded in recent years because banks, chasing profits, are largely ignoring regulations and laws meant to govern their operations and thwart fraud, experts say.

The banks and the federal government know the scope of the crime but have failed to take meaningful action. The roster of banks that have approved stolen and fictitious identities to open sham accounts includes almost every major banking institution in the country, from JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo to TD Bank, according to court documents and banking industry officials.

Spokespeople for Bank of America did not return requests for comment. Wells Fargo declined to comment. A TD spokesman said, “To protect our customers and the bank, TD has strong processes in place to identify, investigate and deter potential fraud.” The American Bankers Association declined to comment.

The silence and inaction infuriates other banks that successfully deter the opening of drop accounts but whose customers — and the institutions themselves — suffer the consequences in fighting the problem.

For example, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency provided a loan for a water project in a town of 20,000 people. To repay it, the town owed the agency about $53,000 per quarter.

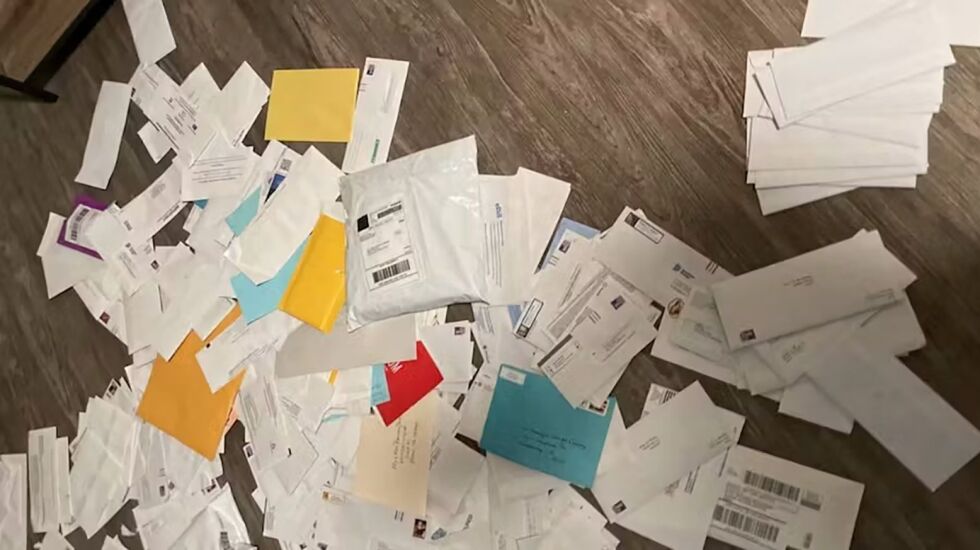

But one of the checks for that payment, drawn on the town’s account at American Commercial Bank & Trust and sent to the state EPA, was stolen from the agency’s post office box. The fraudster scratched out “Illinois EPA,” scribbled in “Bob’s Cigar Shop,” then deposited the check by mobile app to a drop account at Bank of America.

American Commercial sought reimbursement from Bank of America, which was responsible for depositing a fraudulent check into a sham account. But Bank of America refused to make good. So American Commercial sued.

“It would have been difficult to go back to the customer and say, ‘Sorry, you lost the money,’ and for us to suffer that reputational damage,” said Steven M. Gonzalo, president and chief executive officer of American Commercial, who declined to name the town because of customer confidentiality. “But, if we ate the loss, it would have had a material negative impact on us.”

Under banking rules, one financial institution has 30 days to notify another of a fraud that requires reimbursement.

Bank of America’s response in the suit argued that American Commercial took too long to report the scam. Given the nature of the crime, it took more than 30 days for the Illinois EPA to decide the town had failed to pay its bill and notify it of the default, after which it would have to try to figure out what had happened and then call American Commercial, which would have to conduct its own inquiry.

Because of the nature of the fraud facilitated by Bank of America, it could be cleared of all responsibility — and innocent victims would take the hit.

In this case, American Commercial was lucky. In endorsing the check, the fraudster made a mistake that should have led Bank of America to decline the deposit. Since it didn’t, it was forced to repay American Commercial.

“I can’t litigate against the big banks consistently,” Gonzalo said. “So we’ve gotten very good at making demands. Now, we are not shy to tell the other bank that we are willing to report them to the regulator and talk to reporters about what they’ve done.”

Identities for sale

A robust, anonymous online marketplace provides everything an aspiring criminal needs to loot billions and open fraudulent accounts, including video tutorials and handbooks that describe tactics for each bank, Georgia State researchers and The Conversation discovered.

On Telegram, an encrypted messaging app, channels often show photographs and videos of credit and debit cards obtained through stolen or fictitious identities. They also display other goods that are for sale, including existing drop accounts, ATM receipts showing an account balance, stolen and counterfeit checks, fake Social Security and ID cards and more.

Prices vary based on the qualities of stolen or fake identities. For example, longstanding identities with good credit scores are worth more than freshly purloined ones.

One Telegram fraud marketplace offered a nine-year-old identity with a perfect payment history, three open payment cards at three banks and an 800 credit score. The price: $2,500.

Recklessness of big banks

A litany of anti-money laundering rules imposed as part of the U.S. Bank Secrecy Act mandate that banks verify who they are doing business with. Before opening an account, they must gather identifying information of potential customers, analyze those credentials to confirm they are real, confirm sources of money, and more.

In the past, applicants sat with a bank official while opening an account but the digital age changed that.

Legitimate customers opened 13.1 million new bank accounts in 2022 through phone apps and websites, according to Insider Intelligence, a market research company.

To win new depositors, banks make sure the digital application is fast. According to Insider Intelligence, abandonments of partially finished digital applications surge if the process takes longer than five minutes. When customers use mobile devices, the rate can be as high as 40%.

With banks at risk of losing legitimate customers if the application process takes longer than most pop songs, the pressure to ease identification requirements is huge. And that, fraud experts say, is leading to a collapse in the banks’ adherence to anti-money laundering rules — and fueling the boom in drop accounts.

“If banks slowed these account openings until they could conduct more verification on customers, that would be a very good control” to prevent the opening of drop accounts, said Dante Tosetti, a former Federal Reserve-commissioned bank examiner who is now a special adviser to West Coast AML Services, a consulting firm on money-laundering laws. “But they don’t do that because it doesn’t fit their business plan.”

Community banks lose

Officials of smaller community banks — where accounts are usually opened in person — react almost in disbelief that their mammoth, international brethren rushed so quickly into digital banking without preparing for the onslaught of fraud certain to follow.

“That these accounts are being opened shows that the banks don’t have robust [anti-money-laundering] programs and that the regulators aren’t making sure that they do,” said David G. Schroeder, senior vice president of the Community Bankers Association of Illinois.

The community bankers’ group in Illinois has taken the lead in fighting big bank intransigence and has begged federal regulators — the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Reserve — to intervene.

For 2022, the community banks in Illinois experienced losses of $30,000, on average — a huge sum for institutions their size that can impede operations. If that average holds at the 4,548 community banks around the country, more than $136 million was drained from these institutions last year through frauds facilitated by drop accounts at the big banks.

Industry regulators are negotiating a framework with the Illinois association to handle the problems caused by the failures at the financial conglomerates.

Illinois officials have discussed what they are doing with other community bank associations in hopes they will also contact regulators.

But there is a long way to go.

“We’re just in the fourth inning,” Schroeder said. “We are hoping to build some momentum and have an agreement in the next six months or so.”