This is why bank shareholders shouldn't expect such big returns – their risk is lower. In what other industry would they be rescued by regulators?

Analysis: Banks closed 29 branches last year, removed 110 ATMs, and according to their union, many bank employees received real-terms pay cuts.

At the same time, banks hiked the interest rates they charged mortgaged homeowners faster than they increased the rates they paid depositors, if Reserve Bank Governor Adrian Orr is to be believed.

Last week's plea from Stephen Rod of Forrest Hill, in a letter to the editor of the NZ Herald, was forlorn and familiar: "If then, banks are making record profits why are their services to their customers being seriously curtailed? Branches are closing, there are no banking consultants that you can discuss banking issues with at a desk...."

Even as the United States, Japan and Switzerland were bailing out their banks, New Zealanders were calling for a Commerce Commission inquiry into the profits made by theirs.

READ MORE: * Fisher Funds loses $80m-plus in US bank collapse * Amid fears for small players, big banks agree to a competition inquiry * Growing momentum for 'David and Goliath' Commerce Commission inquiry * Reserve Bank would back a Commerce Commission inquiry

So are our banks as flush as we think, or should we be more concerned about their resilience to rising interest rates and global financial turmoil?

"Bank profits are extracted from our communities," says First Union research Edward Miller. "It is unclear why we have to endure higher rates of profit extraction than Australian, British, Dutch, Japanese or Spanish citizens."

An answer of sorts is in how we count bank profits, and whom we compare them to. Compared to this country's biggest construction companies, their return on equity is low – but compared to other banks around the world and even their parent companies in Australia, they are making comfortable returns.

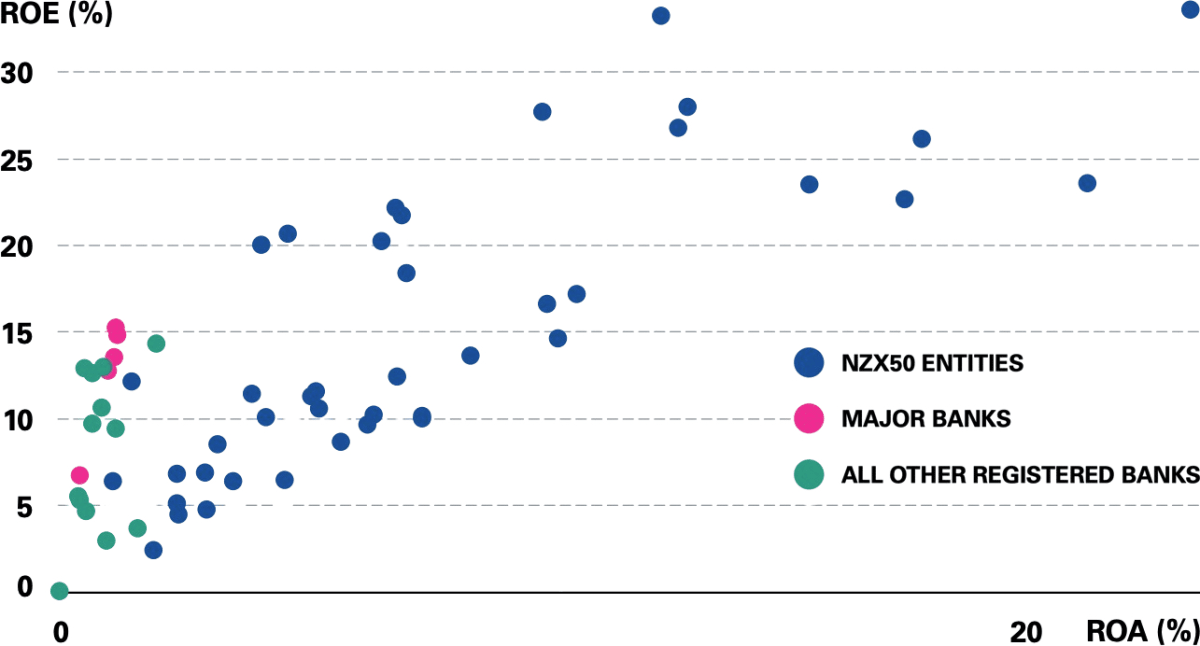

Banks' returns compared to NZ's biggest listed companies

In its annual report on the performance of our banks, KPMG defends bank profits by arguing their return on equity is lower than many of the country's 50 biggest listed companies, those in the NZX50. Similarly, New Zealand's biggest bank ANZ likens its return on equity of about 13 percent to an average of about 12 percent among the top 10 NZX listed companies.

"It's a very disingenuous comparison," retorts Sam Stubbs, the founder of Kiwisaver provider Simplicity. "They know they should not be compared to the NZX10, they should be compared against their parent company in Australia. They're making a much higher ROE than their parent company.

"And they're making a much higher ROE than banks on average globally. New Zealand is one of the most profitable parts of the world for banks, and it's all coming out of our pockets."

Safe as houses

Critically, this week's bailout package for Credit Suisse has shown exactly why banks shareholders shouldn't expect such big returns. Their risk is lower. In what other industry would shareholders be rescued by regulators?

One of the first things Econ 101 students learn is about moral hazard: that regulators shouldn't provide investors an incentive to take risks while being protected from its consequences. Yet that's exactly what happened with the bailout for Credit Suisse: the Swiss Bank's shareholders (first and foremost, the Saudi National Bank) will get US$3.25b in shares in UBS, the company that has taken on Credit Suisse's assets and liabilities.

In America, too, federal regulators coordinated with 11 big banks to deposit US$30 billion into First Republic, a wobbly regional bank, to secure not just its depositors but also its shareholders – among them many KiwiSaver 'growth' and 'aggressive' funds.

"The Credit Suisse takeover deal brokered by the Swiss government over the weekend broke all the rules, leaving money on the table for shareholders while wiping out additional tier 1 (AT1) capital holders." – Peter Garnry, Saxo

The biggest banks have always been considered "too big to fail". The impact on the economy would reach far beyond the banks' own shareholders, bondholders and depositors. Traditionally, the first approach is to try to keep the bank afloat – as with Credit Suisse, as with First Republic, and as with the New Zealand Government's $380 million bailout of BNZ in 1990.

If that can't be done, then governments and the industry will try to minimise the harm to depositors, who are considered to have placed their money with a bank for safe-keeping – not as a cash-earning investment.

Now, with the Credit Suisse bailout, the Swiss regulators have gone a step further by allowing shareholders to realise some of their equity.

Reuters reports the Swiss authorities' handling of the Credit Suisse rescue has "up-ended the markets' expectation that shareholders would take a bigger hit".

And Saxo equity strategy head Peter Garnry says that by leaving money on the table for shareholders while wiping out additional tier 1 (AT1) capital holders, the takeover deal "broke all the rules".

So it seems clear that an investing risk that was already low is becoming still lower, as of this week. Bank shareholders should expect lower returns, accordingly. This means more of the revenues should be retained in the companies – and in a genuinely competitive market, some would be returned to customers in the form of lower bank fees and interest rates.

If that's not happening, then that's an argument for an inquiry into barriers to competition in the industry – that same proposed Commerce Commission market study that has gained so much public and political momentum, since Reserve Bank chief economist Paul Conway mooted it here at Newsroom Pro last month.

Why do we look at profits?

There are two ways to come at this: from the customer's perspective, or from the institution's side of things.

Ultimately, it's the prices, products and services the banks deliver for their customers that should matter the most to competition regulators.

"They have been very quick to increase their mortgage lending rates, but deposit rates have lagged behind." — Adrian Orr, Reserve Bank

That's why Reserve Bank Governor Adrian Orr highlighted a perceived discrepancy between what banks will pay to use your money, and what they'll charge you to borrow their money.

"What we are calling out across the banks is they have been very quick to increase their mortgage lending rates, but deposit rates have lagged behind and bank margins are holding up," he said, announcing the latest official cash rate increase last month. "Higher deposit rates are a critical part to encourage savings, which takes inflation pressure out of the economy."

But it can be hard to compare apples with apples when a dozen local banks are providing thousands of products to millions of customers – so the other way to assess how competitive the market is, is by measuring how big the profits are being made in it, by the institutions.

"If you think about pre-tax profits, which is the real number, it's almost $2000 per New Zealander per year, including childen." – Sam Stubbs, Simplicity

The well-established economic theory is, if there are excessive profits being made in an unfettered markets, then new competitors will enter the market and offer their products at a lower price in order to get their share of those big profits. If new entrants aren't entering and dragging down the profits, then either there are barriers to their entry – or the profits aren't as attractive as they may first appear.

"Whenever we have an industry sector that is dominated by a handful of strong players, I think it warrants an investigation whether there actually is enough competition," says Dr Christoph Schumacher. "We've seen it in the petrol industry, we've seen it in supermarkets. So absolutely, there's no harm in any sector that is dominated by a few strong players to ensure that there is actually free competition."

A more vexed question is how to measure those profits – and since Paul Conway gave his attention-grabbing interview to Newsroom, every bank and his dog has proffered a view on that.

1) Profit before tax

Sam Stubbs has long been outspoken in his calls for an inquiry. "If you think about pre-tax profits, which is the real number, it's almost $2000 per New Zealander per year, including children," he argues.

"We need a proper Commerce Commission inquiry. Why? Because banks make well over five times what supermarkets make, and many times more than the building industry, and they have both been investigated. So why not investigate our most profitable industry, by far?"

Just a little further up the road at Massey University, Schumacher is Professor of Innovation and Economics and director of the Auckland Knowledge Exchange Hub. He's also a proponent of a Commerce Commission inquiry.

"Private customers are saying, hey, I pay that much extra so that banks, who are in big fancy buildings, make even more money and make record margins and huge profits," he tells Newsroom. "The 2022 profit was higher than ever before. In each quarter, profits have increased."

One might think those who support an inquiry into bank profits might highlight the biggest dollar figures – and certainly, Schumacher does that. In KPMG's Financial Institutions Performance Survey, published last week, he forecasts the New Zealand banking industry's profit before tax will top $10 billion this financial year. "So there is certainly an argument that maybe they could make a few dollars less, and that might ease the pain on the public who have to pay their interest."

But although he reports on profit before tax, he's first to admit that isn't the most useful metric for this purpose. For a start, it clearly doesn't allow international comparisons between different tax jurisdictions.

Instead, for the purpose of diagnosing whether profits are excessive, he points to the quarterly and annual increase as a more useful measure.

2) Rate of profit increase

Rather than looking just at the total gross profit at a point in time, Schumacher argues that it's more useful to consider how fast that's increasing.

"When you see an industry sector increasing their profit regularly, there could possibly be an investigation into whether everything is fine," he says, somewhat equivocally.

Then, with greater certainty: "Yeah, absolutely."

Banks' steady increase in quarterly profit before tax (1yr rolling average)

He's not the only one who talks about rate of change: Stubbs says the margins for banks in New Zealand have gone up about 23 percent in the last two years.

"Remember that's in the context of banks shutting branches and making it very, very difficult for some people to get banking services," he says.

But other aren't looking at the increase in before-tax profits – they're comparing the net profits after tax.

3) Net profit after tax

This is where a consensus begins to build about which metric to use.

Here are a few pundits who have looked at net profit after tax. There was former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern: "We've seen this consistently, them posting significant profits," she said in November. "I think questions need to be asked to managers of these banks as to whether or not they are serving their communities well."

The Green Party's Chloe Swarbrick agrees that through no virtue of hard work or innovation, banks have benefited from fortuitous circumstances allowing them excess profits. "That is $180 a second after tax, and again in a context where so many New Zealanders are struggling, that is absurd."

"You might think of profits as something banks take out to pay shareholders for their investment and to reinvest in their business. On the flipside, they also put money into our economy by running their businesses here and paying tax." – Roger Beaumont, Banking Association

National Party finance spokesperson Nicola Willis says: "This comes at a time when bank profitability is high, even while access to credit has become harder for some borrowers and many mortgage holders are feeling crushed by rapidly rising interest rates. New Zealand bank customers deserve answers...."

And it's not just the critics: KPMG, in its annual survey, dedicated a chapter to defending the banks' profits. It uses net profit after tax to calculate return on equity, and return on assets. So too the country's biggest bank, ANZ.

NZ Banking Association chief executive Roger Beaumont says we often hear about bank profits going overseas. "That’s half the story," he argues.

Three big banks increased return on equity in 2022

"You might think of profits as something banks take out to pay shareholders for their investment and to reinvest in their business. On the flipside, they also put money into our economy by running their businesses here and paying tax.

"Last year banks made a net profit of $7.18 billion. They also spent $6.35 billion running their businesses here and paid $2.75 billion in tax. That’s a total contribution of $9.1 billion which, when compared to the $7.18b profit, results in a net positive contribution to our economy of $1.92 billion. And that’s before you take into account the contribution banks make in funding household and business needs."

Beaumont says profit going overseas is half the story; so too, net profit is only half the equation.

If one divides a bank's net profit by its equity, or its assets, then one starts getting more meaningful measures – and also, sufficiently complex that they can't easily be used in heightened election campaign rhetoric!

4) Return on assets

Return on assets is calculated as net profit after tax, as a percentage of a bank's total assets.

KPMG argues that this alternative profitability measure comes in at 1.08 percent for the year, for banks – this is "significantly lower" than the 7.60 percent return on assets achieved by the NZX50 companies, based on their latest financial statements.

But Stubbs and others have already discounted comparisons with big listed companies from entirely different sectors like construction and tech development – and even KPMG admits that. "This measure is impacted more by the industry that an entity operates within, and therefore, is not so comparable."

5) Return on equity

That brings us to the most favoured measure: return on equity. These seems to be some consensus that if the Commerce Commission inquiry were to be into bank profits (and we've already suggested it should actually be into the products and services they provide New Zealand customers) then this would be the best way to measure those profits.

Westpac spokesperson Will Hine says return on equity is a more useful measure of profitability than headline profit figures, which can be misleading. "New Zealand banks generally hold much higher levels of capital than other banks overseas and other companies operating locally in New Zealand," he argues.

He compares Westpac NZ's 12.1 percent return on equity, at 30 September 2022, with the 15.0 percent average for NZX50 listed companies.

So, too, ANZ and KPMG rely on those comparisons with big listed companies. "Although the banking sector provides a range of essential services and is fundamental to our economy, some will say that the profits are still not justifiable," the consultancy says in its survey report.

Return on equity allows fair comparisons between companies, it continues. It is calculated as net profit after tax, as a percentage of average equity through the period.

The New Zealand banking sector had a return on equity of 13.4 percent, lower than that 15.0 percent average for NZX50 companies. "This shows that comparative to their size, the profits made by the banking sector are in fact marginally lower in comparison to 50 of the largest listed companies in New Zealand," KPMG says.

"Everyone already knows there’s a problem here so we want to focus on immediate solutions." – Edward Miller, First Union

Yes, but – this is still based on the dubious comparison with companies in entirely different sectors, with different inputs and outputs and very different regulatory environments. An exporter like F&P Healthcare doesn't have the same weight of domestic regulation and compliance that a bank does, so of course its returns might look better.

First Union, which represents bank workers, argues that a more useful comparison is with overseas banks. Edward Miller, a research and policy analyst with the union, has averaged a decade’s worth of World Bank data to show that New Zealand banks’ returns on equity are among the highest of our standard comparator countries.

While First Union's 2012 to 2021 average is useful in providing a big dataset, it fails to recognise that some countries' bank returns have steadily trended up (like the UK and Slovenia) or down (like China). It gives too much weight to what was happening more than a decade ago.

So Newsroom has instead looked at just the most recent World Bank data, charted below.

NZ banks made some of the highest returns on equity in the OECD (2021)

Similarly to Miller's analysis, this shows New Zealand banks' returns are still well above average – the sixth-highest in the OECD. (For comparison purposes, Russia and China are also included in the chart though neither is presently an OECD member).

Miller agrees that a Government inquiry into bank profits is necessary – but the union would also like to move immediately to pinging those profits.

"It's an outrage and absolutely unfair." – Anthony Albanese, Prime Minister of Australia

"Everyone already knows there’s a problem here so we want to focus on immediate solutions," he says. "We would like to see an additional 5 percent levy imposed on the profits of any bank that earns more than half a billion in annual profits, to fund the establishment and operation of a Ministry of Green Works."

Again, this is problematic, because it simply penalises the biggest banks rather than those extracting the highest share of profits. If ANZ or BNZ wins customers by offering the lowest mortgage rates and the highest term deposit rates, should they be penalised more than a smaller bank that ignores any wider responsibility to the community and services only the super-wealthy, thereby returning big dividends to its shareholders? (And yes, that does happen).

NZ banks make bigger returns on equity than Australian parent companies

Rather than comparing the New Zealand banks to their counterparts around the world, Sam Stubbs opts for the obvious solution of comparing them with their Australian parent companies – because the bank profits concerns is largely around the "big four" Australia-owned banks.

This shows a quite marked discrepancy between the high returns the NZ banks send back to their Australian parents, and the lesser returns that those Australian banks deliver to their shareholders. For instance, Westpac Australia's return on equity was 7.5 percent – but Westpac NZ returned 12.7 percent, more than five percentage points more.

This suggests that the banks compete harder for their share in the Australian market then they do for their share in the New Zealand market – and Aussie bank customers are the winners, as a result.

This is made the more remarkable because, even across the Tasman, there are concerns that they are making a killing off the little guy.

Last month, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese slammed Australian banks for hiking mortgage rates, while failing to increase interest rates for savings accounts. "It's an outrage and absolutely unfair," he said.