Kesrewan* holds herself upright and speaks confidently, even though English is her second language. But she admits that her “heart is beating faster”. Talking to us is reminding her of her most recent failed job interview – one of many since she arrived from the Middle East seeking asylum more than 20 years ago.

Kesrewan, now in her 50s, is a pragmatic woman but she grows emotional telling her story. She wishes she knew why her latest interview for a staff job at the information service where she already volunteers has again been unsuccessful. She would like some feedback on what she did wrong, or how to improve.

Aged 30, Kesrewan arrived from the Middle East as a highly qualified woman with experience as a newspaper editor and librarian. Yet despite her best efforts – taking multiple classes, working voluntarily to maintain her skills, helping out in community organisations – she has always struggled to translate this into meaningful work in the UK.

Given her limited language skills and with children to support, once she gained legal status she initially took on any work she could find, such as cleaning and kitchen jobs. She thinks her employers often preferred that she had no English because she could not complain about the conditions. She says she was “too ashamed” to tell family and friends in the UK and back home about her cleaning work.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

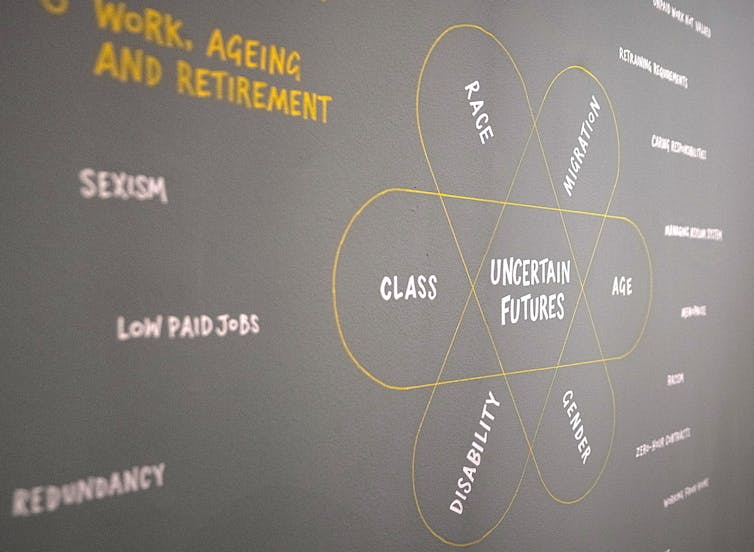

Kesrewan’s story is indicative of most of the 100 women aged 50 and over that we have interviewed for the Uncertain Futures project. All live in Greater Manchester, often precariously. Not all are permitted to work in the UK, but those who do typically struggle to find secure, full-time employment.

New research by the Chartered Management Institute (CMI) has found that UK firms and public services are much less open to hiring older workers than their younger peers. Its survey of more than 1,000 managers found that just 42% were “to a large extent” open to hiring people aged between 50 and 64, compared with 74% for those aged 18-34 and 64% for 35 to 49-year-olds.

Our interviewees typically work in kitchens, warehouses, or as cleaners maintaining the environments of offices, schools and high-street stores. Others work in badly paid or voluntary care roles, supporting older people and those with disabilities. Most who do get paid are on zero-hour contracts. Many describe having experienced abuse and discrimination.

Kesrewan now seems resigned to her “life in the shadows” – struggling even to secure the kinds of job that the UK desperately needs to fill but which offer little reward and poor conditions. Women like her are largely unseen and their voices usually go unheard – whether because of their lack of English, their employers’ failure to recognise their experiences and skills, or the blind eye that the authorities and general public often seem to turn to them.

“I haven’t done enough jobs – I didn’t have the chance,” she reflects sadly. “Really that’s confusing for me. It wasn’t like me to sit at home and not want to get a job.”

A ‘watershed moment’

The COVID pandemic was briefly imagined to be a watershed moment for “invisible workers” in the UK and elsewhere. Jobs that had traditionally been undervalued were now understood to be “essential”. The importance of keeping workspaces clean and germ-free was suddenly appreciated. Carers, nurses, bus drivers and many more put themselves at enormous personal risk to keep people safe and society functioning. Volunteers stepped in to help the vulnerable when statutory support all but collapsed. Many people died because of the work, paid or unpaid, that they continued to perform.

Löis, who works full-time while also caring for her mother who has dementia, describes the countless attributes required of carers like her:

You have to be kind, patient. You have to be a good planner. You have to be able to pick up the unexpected, mentally, physically. You have to coordinate the services that may or may not help you.

But Löis struggles with the idea that none of this is recognised as a skill, or as experience which is valued by society. When she asks herself what all of this is worth, she replies quietly: “I’m not sure.”

For Kesrewan too, it is a source of pain to feel so invisible. While she has helped younger, more inexperienced volunteers to secure paid roles, she feels her age is now an additional factor hindering her own ability to get a job. She has applied five times for a paid role in the information service where she has volunteered for seven years, but has always failed at the interview on the grounds that she does not have “sufficient experience”. She feels sad that discrimination based on age – “coupled with your skin colour, your background, your nationality” – is still so prevalent in recruitment practices.

The cruel irony is that there are now severe labour shortages across the UK’s care, health and social work sectors, and in some administration and office support activities. Non-British migrant workers are over-represented in these sectors but, despite the pressing need to fill these roles, they are often non-permanent jobs offering only zero-hour contracts.

The women we meet are keen to work hard in fulfilling roles that support themselves and their families. Some have little understanding or knowledge about retirement and pensions, and many express deep concern about whether they will ever earn enough money to retire. Gemma, 59, says she can see herself “cleaning toilets till I’m 85”, adding:

You’re always scrabbling to pay rent in the private sector – it’s very expensive and precarious. I think I could live on the living allowance [state pension], but I might be living in a treetop in a park to do it.

Degrading work

Many of the women we meet are extremely well qualified, but that hasn’t stopped them experiencing degrading working situations. Azade is 60 and her story is fairly typical.

Qualified with a degree in agriculture from a university in the Middle East and with many years’ experience in gardening and managing farms, Azade arrived in the UK 24 years ago with two little girls – one of whom had been born en route. “Very long travel,” she recalls. “I have my baby on my way as it was a really awkward time.”

Needing to support herself and her children, Azade was only able to work after securing her refugee status, which took two years. She initially sought out work as a tailor but describes the conditions as “slave work – for a very, very small amount of money. But still I had to do it because I am a single mum with two children.”

She went on to study accountancy but has not been able to secure any work as a qualified accountant. Instead she works as an agency interpreter, but describes the unfair power dynamics within this work:

If you are late by five minutes, they charge you £25 – [yet] they pay me only £14 for one hour … If you are late by ten minutes, this would be classified as “did not attend” and they charge you £100.

Equally, if a client cancels a video call at the last minute, Azade does not get paid. This is essential work, assisting people to communicate with state and semi-state agencies about their legal situations and health matters. Yet there is little value or respect attributed to the role, as a result of the unstable nature of the agency’s relationship with its employees.

Other women describe outright discrimination and racism as a regular part of their work. Much of it goes unreported, let alone addressed.

Murkurata trained as a nurse after arriving from Africa in 2001, where she had worked for more than 20 years as a civil servant. She had expected to continue in a similar line of work here, but says when she arrived here she was “shocked … I got no response. Nothing. Nothing. I don’t think anybody looked at my papers. So I went to nursing and loved it, because I was touched by the people I cared for.”

At the same time, however, Murkurata speaks candidly about being undermined in her role by other nursing staff, including those of a lower rank:

I was the nurse in charge. But the carers, because they are white, they want to tell me what to do with my patients … If I tell them what to do, [another nurse] might tell me that she has been there for years and she knows better. They really, really undermine your intelligence and understanding, you know.

She also recalls a number of occasions when her patient would ask for a “proper nurse” on seeing that she was black. The managerial support given to her in such circumstances would vary, she says:

Some managers were very good, but others would just let this happen. So sometimes you just end up not saying it because it’s pointless. Even if you tell them that’s what they a patient is saying, somebody will always say: “It’s nothing, just brush it off … it’s nothing to talk about.”

Murkurata – who is now training to be a church minister – wearily complains that this effectively put the blame on her for such behaviour by patients:

I’m giving this person care and I’m the one who is at the receiving end. I don’t deserve that kind of treatment, because I’m trying my best and just a human being, just like anybody else … But whatever goes wrong, they find a black person to blame for it. When we are in the same ward working, if you leave a catheter not emptied because you are white, it’s OK. But if it’s [a black nurse] who leaves it unemptied, everybody in the ward should know it.

Feelings of uselessness

A November 2022 report by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation highlighted the increasing numbers of UK adults who are struggling both financially and with mental health problems. Many of the women we meet fit this demographic: limited financial security for housing and necessities, reduced standard of living, and poor health and wellbeing (which itself can exacerbate poverty).

Just under two-thirds of the women we have interviewed are from black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds. All are heavily over-represented in shift work and non-permanent jobs in the UK. A quarter of UK adults in “deep poverty” are from minority ethnic populations.

Their lack of financial security may stem from unemployment, poor and precarious working conditions, or a lack of financial provision in retirement. The cost of living crisis – which research shows is being felt harder by people living in the north of England compared with much of the south – is increasing the pressure on them to work for longer (both each day and before retiring), even in very difficult conditions.

Mari, who was in the UK asylum system for five years, describes the feelings of uselessness associated with the inability to secure paid employment – and how this feeling was made worse by the pandemic. Her voice softens and quietens as she echoes: “Long time to stay home, stay home, stay home.”

She fled to the UK from the Middle East without her children because she was facing “great danger” as a newly divorced woman. She had previously worked for more than 20 years in banking, and although she arrived speaking very limited English, was optimistic about the many transferable skills that she could use here.

The reality, she says, has been very different. Throughout her interview she remains stoical as she describes obstacle after obstacle: being refused English lessons after her initial asylum application was declined; spending time in a detention centre and facing potential deportation; “shaking” every time she came into contact with the police; becoming ill and temporarily losing her eyesight to a thyroid disease while waiting so long for her asylum application to be processed.

Mari, who is now in her 60s, has worked hard to overcome all these challenges. She has picked up “street English’” through speaking with friends. Her eyesight recovered and she was granted leave to remain in the UK, but the stress of the limbo she was living in remains with her. Having previously always worked in a respected professional role, she says this period has altered her life completely:

Those five years were very difficult, because they don’t allow any work, just voluntary – no college, no job, no anything. When you can’t go to any job, the first thing is you think you are not useful, you are not able to do anything. This feeling is very bad.

At one point during her interview, however, Mari becomes quite emotional as she speaks about the voluntary organisation which supported her during this difficult time:

Sorry… My life … All my life, it’s thanks to them.

She is talking about one of the 90-odd organisations throughout the UK that provide essential support for asylum seekers and refugees. Mari attributes much of her current, more stable situation to this organisation.

With its help, she has managed to take up voluntary roles which make her “feel good” and give her “hope”. She works as a cook for a local charity as well as helping to care for her grandson and older neighbour, who is 97. But she wants to earn her own money and gain the independence that would come from this. She says she will do anything – for example, “packing at home for retail companies, packing clothes.”

But it is not only community organisations that can have a major impact on the lives of undervalued women such as these. Enlightened employers have an important role to play too – one which could also pay dividends for their companies.

A better future?

FemmeCapable, 54, embodies the tenacity we see in so many of our interviewees. Struggling with her English and experiencing prejudice in her role as a care assistant – “I faced discrimination a lot” – she retrained herself using every community resource she could find, then established a mobile food business selling barbecued African cuisine. At the same time, she set up a charity supporting women from ethnic backgrounds in her community.

Even when COVID shut down her business, FemmeCapable used her entrepreneurial skills to transform it into a mobile food response team, part-funded by her local council, which provided culturally appropriate food and transport to families in her local area. She was effectively a frontline worker during the pandemic, even though her work was not perceived in this way.

Her enthusiasm, intelligence and drive permeate the interview. She oozes energy to create something and “make it real life”, and to “share it with the public or the world” so it can have lasting value. Yet her nursing contributions have been overshadowed by racist attitudes, and her work in the community has largely gone unrecognised.

FemmeCapable credits her local Council for Voluntary Service for providing all-important support in setting up her business and community organisation, including applying for funding. These services work closely with local councils to help people use their skills and have their contributions recognised – a vital first step in ensuring a better future for older women like FemmeCapable.

However, announcements made in the UK government’s 2022 autumn statement now threaten the existence of these voluntary services. According to the National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO):

[They] are on the verge of buckling under the compounding pressures of increased demand, skyrocketing operational costs, eroding income, and challenges recruiting staff and volunteers.

Such pressures are exacerbated by increased energy costs and cuts to public services. In a combined response, the Institute for Government and the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy noted that public services “not protected in the autumn statement now face day-to-day spending cuts of 1.2% per year on average over the next two years”.

A lightbulb moment

Victoria, 63, migrated to the UK from Africa more than 22 years ago. As her story unfolds during the interview, it shares the trajectory of so many of the other older migrant women we have met: a professional woman spending many years in immigration limbo while volunteering in community organisations to maintain her skills.

She originally came to the UK on a six-month tourist visa, then fell ill with cancer and had to stay for treatment. She applied for an extension to her visa on medical grounds, but the process took over six years to resolve.

Victoria has since attempted to get jobs in banking and finance in the UK, as this is her employment background, but has struggled, she suspects, due to her age and skin colour. She has concerns about retirement due to her fragmented working life, much of which has consisted of zero-hours employment:

I have not worked in this country for long enough. Although I have contributed to a pension, I don’t know if that’s going to be enough to retire on.

However, her story takes a positive turn when she describes a “lightbulb moment” – when she was at last offered a staff job after years of temporary agency work by an employer who is, in her eyes, “different”. She says this employer treats her “like a person”.

Victoria now works full-time as a homeless support officer for a Manchester housing charity. She says, with evident pride, that her employer “wants a workplace that is equal for everyone”, offering personal development programmes and wellbeing support for staff.

It was such a relief to be acknowledged and have someone appreciating you – I must add that this is a white employer and the majority of the workers are white. You can count people of my colour on one hand out of about 500 … But they have given me an opportunity and, from what I have experienced right from the interview itself, they don’t treat me like I am different. You are just a person in a workplace – that’s how I feel, that’s how they place me.

According to the Centre for Ageing Better, there are a multitude of advantages to hiring and retaining older workers – not least, benefiting from their skills, strong work ethic, and experience. They tend to retain business knowledge and networks and, by better matching the profile of customers, can improve services. There are also established benefits to multigenerational teams, both in terms of productivity and in passing on valuable experience to younger colleagues.

Hearing Victoria’s story is a moment for reflection. She shows us there are ways to break the cycle of invisibility; to help these older women’s voices to be heard and their expertise to be valued. But it requires continued financial support for community organisations, and enlightened employers who recognise the skills and experience of older women.

There is encouraging news from Kesrewan, too. After all those rejection letters from the information service, she has just been offered a part-time job as a welfare adviser and outreach worker at a local charity she volunteered with during the pandemic. She can only work ten hours a week, or she may end up financially worse off due to the strict rules of Universal Credit – but still expresses joy that at last her skills are being recognised.

This work for me – it’s life, wellbeing, being fit and active. You see that you have something to offer. You see that they value you. It’s not just because you are working and they pay you. It’s what you can do for the community and others.

For Kesrewan, Victoria and, hopefully, more of the women we have met, the veil of invisibility may finally be lifting.

All names have been changed to protect the interviewees’ anonymity. They were invited to choose their own pseudonyms.

For you: more from our Insights series:

Loneliness, loss and regret: what getting old really feels like – new study

How a photograph uncovered my grandmother’s republican activism during the Irish revolution

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

This project has been partly funded by the Manchester Institute for Collaborative Research on Ageing, Manchester Art Gallery, and the ESRC Festival of Social Science. Both authors are members of the Labour party.

The authors would like to thank the Uncertain Futures Advisory Group: Akhter Azabany, Erinma Bell, Sally Casey, Atiha Chaudry, Rohina Ghafoor, Marie Greenhalgh, Teodora Ilieva, Tendayi Madzunzu, Jila Mozoun, Elayne Redford, Charity Rutagira, Nadia Siddiqui, Circle Steele, Patricia Williams and Louise Wong. Thanks also to Suzanne Lacy, who led the participatory art and research project, Ruth Edson at Manchester Art Gallery, and research assistants Tanya Elahi, Lila Nicholson, Amanda Wang, Jess Wild and Robyn Dowlen. And to the 100 women who participated in the research and shared their stories.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.