The ancient Aztec and Mayan civilisations were perhaps the first to begin making paper out of sisal leaves. Since then, the stiff, green sword-like leaves have been used to make twine, cloth, and carpets. The plant itself is also used to make mezcal, a distilled alcoholic beverage.

Now, in a move to make menstrual hygiene products more environmentally sustainable, scientists at Stanford University have reported a method to produce from sisal leaves a “highly absorbent and retentive material”.

As a result, the researchers posit in their Nature Communications Engineering paper, the material can potentially replace cotton, wood pulp, and chemical absorbents in sanitary napkins.

The absorption capacity of the material is higher than those found in commercial menstrual pads, they add.

The study’s authors also claim that their method uses no polluting or toxic chemicals, can be carried out locally at a small scale, and is environmentally sustainable.

Led by associate professor of bioengineering Manu Prakash, the team is currently working with a Nepal-based non-governmental organisation to test whether their method can be scaled up to mass produce sanitary napkins and meet the growing demand for low-cost and ‘green’ menstrual hygiene products.

Access to hygienic menstruation

In 2022, the Centre for Economic Data and Analysis at Ashoka University reported that there has been a significant rise in the number of people using hygienic methods – i.e. sanitary napkins, tampons, and menstrual cups – to manage their menstruation in India.

Despite this promising growth, access to menstrual hygiene products remains limited for around 500 million people worldwide. In rural India, for example, only 42% of adolescent women use exclusively hygienic methods to manage their periods.

One key barrier in making menstrual hygiene products, like sanitary napkins, accessible is the rising cost of raw materials and distribution.

The absorbent material in sanitary napkins is often a combination of wood pulp and synthetic superabsorbent polymers (SAPs). The latter are materials that can absorb a large amount of fluid relative to their own mass.

Even as State and Central governments in India are working to make sanitary napkins available widely at lower prices, experts say that their widespread use is environmentally unsustainable.

According to gynaecologist Shehla Jamal, founder and president of the Society for Menstrual Disorders and Hygiene Management, “Menstrual sanitation waste is adding non-biodegradable waste in the environment [in bulk],” and in turn, constituting an environmental hazard.

For example, according to estimates from a 2022 United Nations Population Fund report, Patna alone discards 9.8 billion sanitary napkins every year. Another estimate from a 2022 study placed the monthly quantity of discarded sanitary napkins in Chennai at 27 million a month.

Dr. Jamal also said that single-use sanitary napkins contain dioxin, which is a persistent environmental pollutant as well as a carcinogen that puts users of sanitary napkins at risk of cancer. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies dioxin as a “known human carcinogen”.

A sturdy succulent

Owing to the growing environmental concerns around menstrual sanitation waste, scientists have in the past pondered over ways to make sanitary napkins more environmentally sustainable. Chandra Shekhar Sharma, a professor of chemical engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology, Hyderabad, told this reporter that other plant fibres – like those obtained from banana plants – have been used to synthesise absorbent material for sanitary napkins.

Prof. Sharma’s group in the past has also attempted to reduce the use of SAPs in sanitary napkins by replacing them with cellulose-based nanofibers.

However, there is one problem with relying only on banana plants for plant-based absorbent materials. Access to hygienic menstruation is most limited in low- and middle-income countries, many of which are located in the tropics and are prone to drought. Banana plants are particularly sensitive to drought and therefore not sustainable choices with which to produce sanitary napkins in areas that are arid or semi-arid and drought-prone.

Enter sisal. Like all succulents, which are plants with thickened parts to store more water, sisal has an uncanny ability to store water and thrive in drought-prone areas. Its leaves grow up to 2 m long. The lifespan of a sisal plant is about 7-10 years, during which it produces 200-250 usable leaves. Each leaf has about a thousand fibres that can be used to make ropes, paper, and cloth. Now, it could be used to make a highly absorbed material as well.

Dr. Prakash first heard of sisal from his friend Alex Odundo, a Kenyan engineer. Mr. Odundo, also a co-author of the paper, has been helping sisal farmers in Kenya grow the crop more efficiently.

“Before sisal, we tested whatever fibrous plant we could lay our hands on,” Dr. Prakash said. Being based in California, the team began with bamboo. The journey to find sustainable absorbent material then took them to Nigeria, Kenya, Nepal, and India, where they tested fibres from banana, rice, and water hyacinth as well.

But according to their tests, “nothing beats sisal,” Dr. Prakash said.

Inspired by termite guts

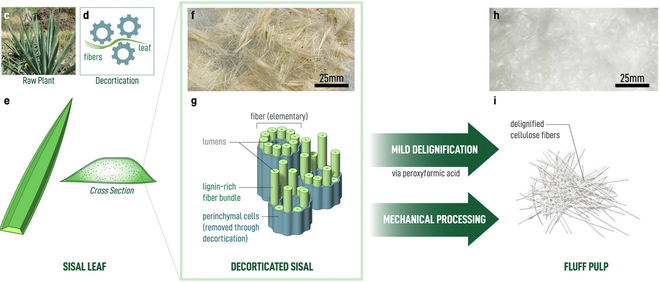

The process that Dr. Prakash’s team has developed begins by feeding sisal leaves into a machine. This machine is a decorticator: it mechanically separates the fibres. In the next step, called delignification, a polymer called lignin, found in plant cell walls that repels water, is dissolved away. What remains is highly absorbent cellulose fibre.

Traditionally, the delignification process for converting wood to absorbent wood pulp involves treating wood chips with a harsh chemical mixture containing water, sodium hydroxide (a strong alkali), and sodium sulphide. This process, called the Kraft process, is effective but also produces volatile and toxic by-products that can cause both air and water pollution.

For a more environmentally sustainable way to delignify sisal leaves, Dr. Prakash and his team turned to the environment – where they found two organisms particularly adept at converting wood to wood pulp: termites and wood-rot fungi.

“Termite guts have an incredible consortium of organisms,” said Dr. Prakash. This consortium, comprising microbes of many shapes and sizes, delignifies wood in a process that scientists don’t completely understand.

They do know, however, that one important compound in this process is peroxyformic acid.

Treatment with peroxyformic acid “selectively removes lignin while preserving the structure of the cellulose microfibers”, the authors write in their paper. The compound can also be reused over several cycles and it decomposes into water and carbon dioxide at the end of the process. This decomposition requires no neutralising chemicals, which minimises environmental damage.

“The amount of CO2 released in breakdown of peroxyformic acid is minuscule compared to the total CO2 in the overall analysis (say, compared to transportation related CO2) or total carbon even in the materials being used itself,” Prof. Prakash said.

Sisal’s fluff pulp

After treating the sisal fibres with peroxyformic acid, the process proceeds by washing them first with a solution of dilute sodium hydroxide and then water. The result is a wet pulp that is then dried and mechanically blended to obtain a dry mass called a fluff pulp.

When the researchers compared the absorption capacity of this fluff pulp to cotton obtained from commercially manufactured sanitary napkins, or Cotton-CMP, they found that the fluff had the upper hand in standard absorption tests.

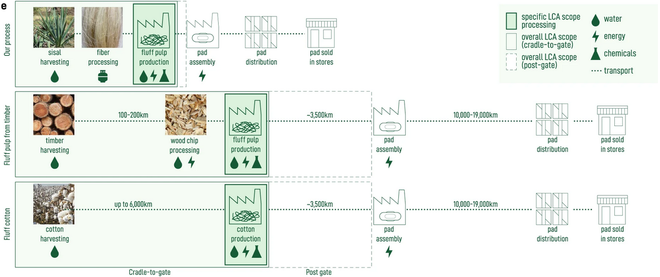

The researchers also conducted a “cradle-to-gate” carbon footprint analysis by estimating the environmental footprint of a product from the extraction of raw materials to the time when it leaves the factory gate.

In what they call an “aspirational case” – when the raw materials, including those required to produce the peroxyformic acid, can be produced on-site using solar energy – the environmental footprint of their process was “comparable” to that of commercial processes that extracted fibre from timber and cotton. The water consumption was also found to be comparable to that of commercial processes to produce absorbent materials from timber, cotton, and papyrus.

Given the cultivation of sisal requires less water and is less environmentally damaging than cotton industries, Dr. Prakash believes replacing cotton-CMP with sisal fluff pulp could make sanitary napkin production more environmentally sustainable in the long run.

According to him, there is a “25-fold difference” in water use “for cultivation and harvesting” “between cotton and sisal”.

He also acknowledged timber could be an alternative to cotton, but only in parts of the world that have an “endless supply of sustainably harvested forests”.

“That’s not an option for places like India or Africa.”

Roping in high-school students

Dr. Prakash is excited for the results of their pilot “at-scale” production in Nepal, where he said he and his team have other grand plans as well. For example, the facility in Nepal won’t only be a manufacturing unit but also a teaching and training site. “We will use this pilot site to teach anybody and everybody interested in replicating this process at scale,” he said.

The team is also starting a global programme to engage students around the world in testing the usability of other plants using the process reported in their paper. According to Dr. Prakash, they “have reported a very general process. Using this process, anybody can test any number of plants.”

In this programme, high school students will be encouraged to test local plants through this process and report their findings in a public database, according to him. Increasing the diversity of plants is important given different geographical regions of the world have different environmental conditions, and different plants that thrive there.

In their paper, the team reported that it has already applied its process to produce fluff pulp from flax and hemp.

Local manufacturing, local control

Dr. Jamal, the gynaecologist, lauded the study but also said that robust research is required to ensure plant fibre-based menstrual hygiene products live up to existing quality standards. According to Prof. Sharma at IIT Hyderabad, “the on-field performance of such plant based fibre products is [often] not at par with existing products”.

To allay concerns around quality, Dr. Prakash’s team is partnering with organisations in Nigeria, Kenya, and Nepal to implement “distributed quality control” of the absorbent material.

The process that the authors describe in the paper is also geared towards “distributed manufacturing” of environmentally sustainable sanitary napkins.

Here, instead of relying on large-scale centralised production, manufacturers work at smaller scales and cater to local populations. Distributed manufacturing also eliminates carbon emissions due to long-distance transportation.

Dr Prakash’s intended partnership, if successful, would also distribute quality control of the sanitary napkins thus produced among more local facilities.

He sees this work as a “research arm” for the movement addressing period poverty and menstrual health, he said. His team is currently building a research consortium where other scientists interested in addressing the lack of access to menstrual products can contribute in an “open source framework”.

Dr Prakash also said they “wish to collaborate with entrepreneurs globally on the ground who are trying to solve the problem from the bottom up, but don’t have the kind of research and scientific resources needed to build high quality products.”

Sayantan Datta is an independent science journalist. They are currently a faculty member at Krea University and tweet at @queersprings.

- The study’s authors also claim that their method uses no polluting or toxic chemicals, can be carried out locally at a small scale, and is environmentally sustainable.

- One key barrier in making menstrual hygiene products, like sanitary napkins, accessible is the rising cost of raw materials and distribution.

- Prof. Sharma’s group in the past has also attempted to reduce the use of SAPs in sanitary napkins by replacing them with cellulose-based nanofibers.