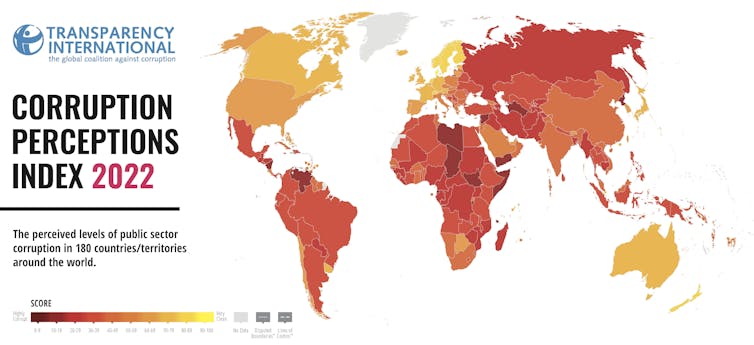

In the world championship of corruption, the competition is fierce. The NGO Transparency International has just published its list of countries according to the level of perceived corruption.

The gold medal in the competition for the most corrupt country has just been awarded to Somalia, followed by South Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, Yemen, Libya, Burundi, Equatorial Guinea, Haiti, and North Korea.

How do you measure corruption in a country?

Since its inception in 1995, the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) has become the world’s leading indicator of public sector corruption.

It ranks 180 countries and territories as more or less corrupt, using data from 13 external sources, including the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, private consulting and risk management firms, think tanks and others.

The scores given – on a scale ranging from zero (0 = high corruption) to one hundred (100 = no corruption), depending on the degree of perceived corruption in the public sector – reflect the opinions of experts and business figures.

When corruption eats away at the state…

Holding the unenviable title of the most corrupt country on the planet since 2007, Somalia has something in common with its “challengers” that explain their high level of corruption. What are the reasons for the link between increased corruption and the multiplication of conflicts?

The first is that highly corrupt societies are characterised by a great weakness of the state. As the most corrupt country, Somalia has almost no state. Over the past 30 years, it has experienced catastrophic famines, failed international interventions, refugee flows, deaths by the hundreds of thousands, and endless corruption, leading to a continued lack of even rudimentary state services and institutions.

Thus Somali law enforcement forces serve only to terrorise the population and enrich themselves and serve their warlord. Somalis live in an environment of pervasive predation, threats and deprivation. Another example is Syria, in which corruption and the civil war have challenged the functioning of the judicial system, a jungle where those who corrupt the judges win the most.

Decaying public institutions

Second, corruption leads to a loss of trust in public institutions, which leads to near-permanent violence. Corruption deteriorates the democratic system in an endless cycle: impoverished citizens receive money to vote for the tyrant in power; electoral commissions are bought and become masquerades to proclaim plebiscites for despots hated by their people; and independent candidates in power are threatened and even sometimes murdered…

For example, South Sudan is a democratic nightmare with permanent violations of human rights – arbitrary arrests, illegal detention, torture and murder. Venezuela, one of the five most corrupt countries in the world, such crimes have infiltrated all levels of the state and corruption has effectively killed the country’s democracy.

Another reason is that corruption fuels war is the lack of press freedom. A tyrannical political system nourished by corruption further reinforces its authoritarianism by destroying press freedom. For example, without any media capable of thwarting his power, Vladimir Putin strengthened his hold on Russia and made it impossible to challenge his country’s territorial ambitions such as the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the 2022 attack on Ukraine.

As for Yemen, a particularly corrupt territory with very little press freedom, the NGO Reporters Without Borders says: “The Yemeni media are polarised by the war’s different protagonists and, to avoid reprisals, have no choice but to toe the line of whoever controls the area where they are located”. As a result, Yemen has been ravaged by war since 2014, fuelled by corruption and an authoritarian press.

The final reason for the link between corruption and war is the importance of economic inequalities and the weakness of economic development.

Rising inequality

In a country where corruption reigns, a small minority monopolises national wealth, especially since corruption is the use of its personal power for private interests against the collective interest. When social injustice reigns, tensions develop and civil wars can break out. South Sudan has been portrayed as a kleptocracy, a governmental system in which the ruling class appropriates public resources for its own benefit at the expense of public welfare.

In the end, the vicious circle has set in: corruption leads to permanent tensions, and then violent conflicts, and then crimes and wars. As the latest Transparency International report shows, highly corrupt countries are all economically, politically and socially unstable territories that are gradually being destroyed by incessant wars. Over the course of the conflicts, all the institutions of governance have been destroyed.

Insecurity encourages the people to engage in trafficking. In the absence of national watchdog agencies, a feeling of total impunity sets in and corruption becomes systemic. The spread of corruption then makes it a social norm, leading populations of the most affected countries to eventually regard it as the only way to survive.

Bertrand Venard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.