Trollies hem the corridor and surround the central nursing hub in the acute centre of Newham Hospital’s emergency department, lined up end-to-end in the humming ward.

Most are occupied: some patients are too ill to sit up, while others are monitored by security. Doctors and nurses are assessing patients as other staff and family members try to squeeze past in the crowded space.

Bright fluorescent lights beam down and dozens of monitors make incessant noise over the chatter of patients, families and hospital workers, with no privacy to speak of.

This is the reality of England’s NHS in winter, with a record 96 per cent of hospital beds currently full.

When we visit, Newham Hospital has just declared it is at Operational Pressures Escalation Level (OPEL) 4 – the highest alert level for a hospital, where rising pressure means the local service is unable to provide comprehensive care.

Anna Morgan, a consultant in emergency medicine and the clinical lead, says corridor care is an unavoidable necessity in an under-pressure department running at double its capacity.

“It is a very crowded, very busy department at the moment, for today and the last few days,” she tells The Independent. “This department was originally built with the idea of having about 250 patients, is what we’re told. And we quite regularly now get over 500 a day... so that is a challenge.”

Gemma Davies, the deputy associate director of nursing in urgent and emergency care, says private areas to carry out personal care or confidential conversations with patients are “at a premium”.

“So all the things that we would normally do in quite a controlled space, and having monitoring equipment, then becomes almost like ‘Move this to there, move that to there, move that’, and it’s almost like playing nursing Jenga with patients,” she says.

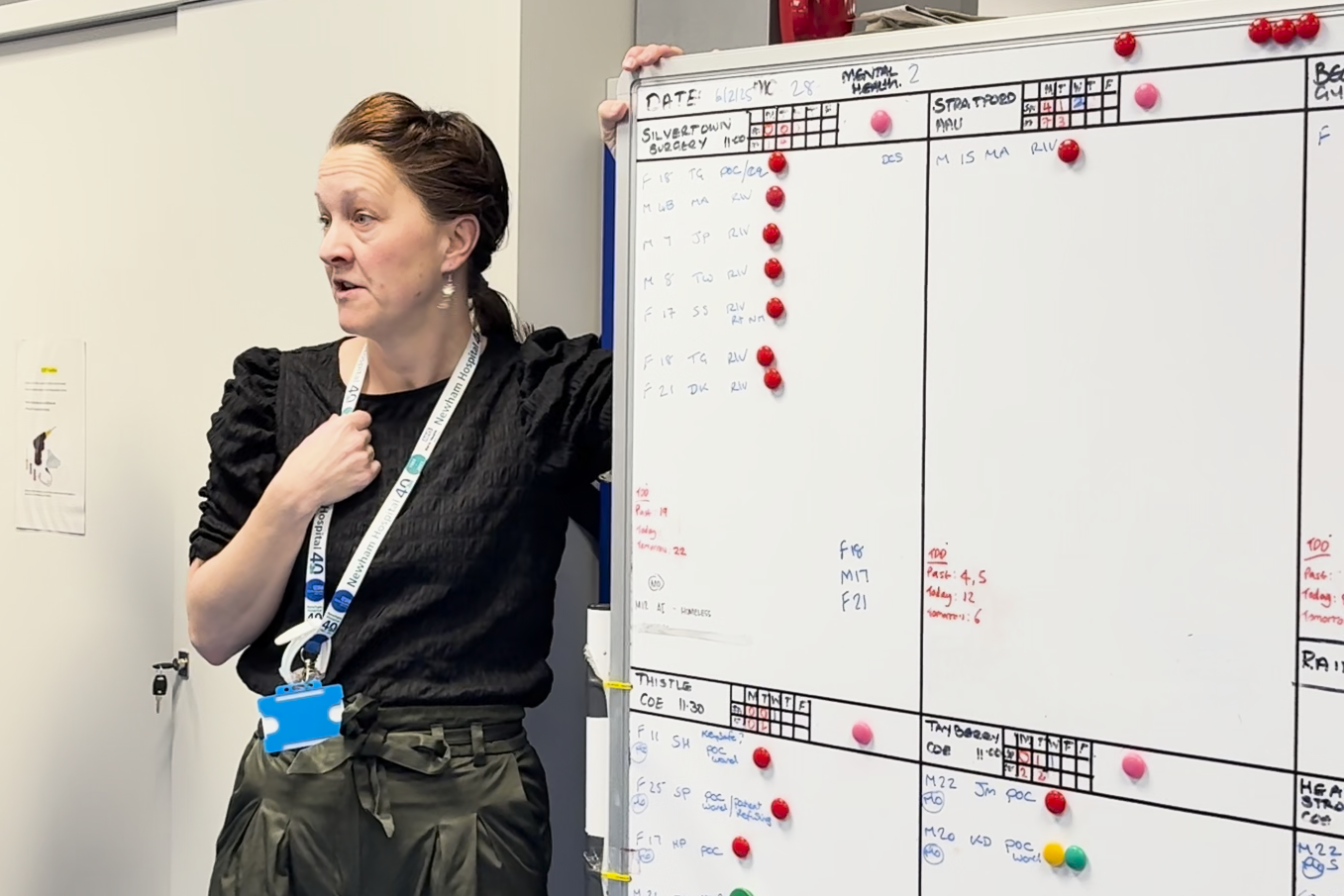

For the doctors, nurses and non-clinical staff, the pressure has been relentless all winter. On Wednesday, nearly 450 patients streamed through the hospital’s A&E department, and staff in Thursday’s morning huddle were warned that a further 424 were expected through the doors that day, keeping the heat on an already stretched department.

Jennifer Walker, the associate director of site operations and community integration, says Newham has made an OPEL 4 declaration every week so far this year.

“During January, the pressure has been considerable and extended,” she says.

“We’ve seen patients [having] extended [waits] in A&E for a long time, a really long time sometimes; we’ve seen higher numbers of patients needing services like mental health in A&E; we’ve seen an increase in children in A&E from respiratory illness; and we’ve had a really difficult time with flu.

“All these things combined have meant that for the staff, and the teams, and the patients, it’s been really difficult.”

It’s a familiar picture in emergency wards across England. Surging winter virus cases have pushed already strained resources and staff past their limits.

Last week was the busiest week for hospitals across England this season, according to the NHS, as cases of the winter vomiting bug norovirus continued to rise, contributing to a record 96 per cent of adult hospital beds being occupied around the country.

Professor Julian Redhead, NHS national clinical director for urgent and emergency care, said: “The twin pressures of winter viruses and problems discharging patients means hospitals are close to full – even as more beds have been opened to manage the increased demand.”

One of the biggest issues with space in the emergency department is finding beds on hospital wards for patients who are critically ill.

Finding those beds is the job of Walker and her operations team, matching the right patient to the right bed and ensuring that discharges happen safely but swiftly.

This is a particular issue in Newham, as the hospital sits within one of England’s most diverse communities, where there are high levels of deprivation.

Walker says a high number of people treated at Newham are homeless or in temporary accommodation. She says she has seen an increase in people waiting for nursing home and residential care placements over the winter, meaning they often have nowhere to be discharged to.

The hospital has worked to help patients in all of these situations, and has managed to reduce its average length of bed stay by one day over the past year, but with increasing numbers of patients each day, Walker says it is hard to keep up.

“We work really closely with partners to try to improve our processes. So actually, we’ve done a lot to make things better, but we just still can’t cope with the demand that’s coming in,” Walker explains. “As an individual, as a leader, I find it incredibly difficult. I find it heartbreaking at times.”

Through the morning, the number of people limping into the emergency department’s main intake area rises, while the specialised waiting rooms begin to fill up. Children and their parents pack out the paediatric area, while others wait patiently in the physical injuries area for their suspected fractures and other ailments to be assessed.

The smaller, specialised waiting areas are part of the department’s attempt to ensure patients are seen swiftly, but all the staff who speak to The Independent acknowledge that sometimes longer waits are unavoidable.

Sarah Nunn, a consultant in emergency medicine, says it can be “really demoralising” when patients are waiting a long time for care, or they are seen in spaces that are not meant for treating people, but the thing that keeps staff going is knowing they are doing their utmost for patients despite the challenging circumstances.

“There’s so many really dedicated, hardworking people that really do want to do the best for our patients under any circumstance,” she says.

Morgan, the clinical lead, says: “Whatever’s going on, the thing that we still have in our power is to be as kind as we can to people, and make sure we do still give them the care that is within our power.”

And people should always seek help if they think they need it, adds deputy nursing director Davies.

“If you come in, I can quite quickly determine what level of care you need,” she says. “If you don’t come in, we can’t have that conversation.”