The spycraft may have been straight out of a Russian playbook, but the game first began with a stroke of pure luck on the part of US-based Soviet spooks.

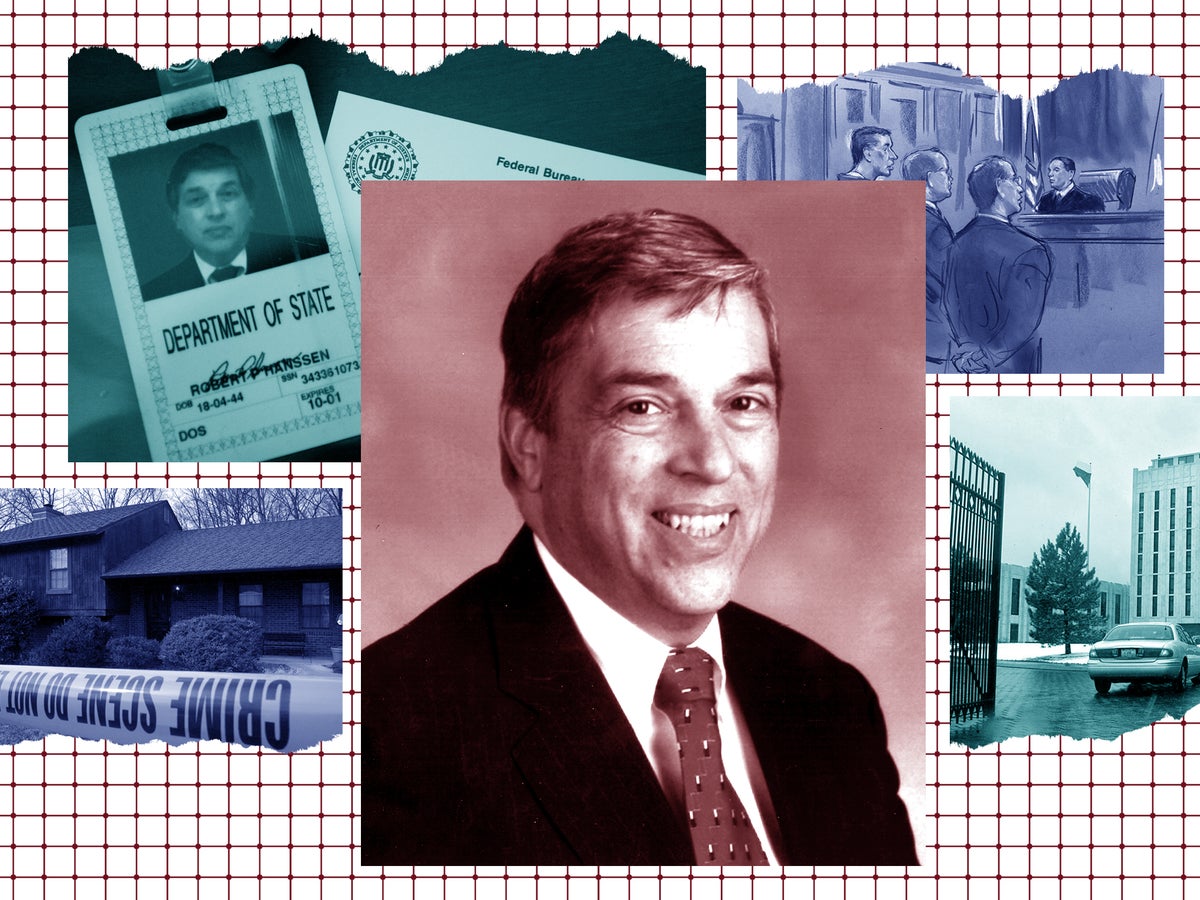

Unexpectedly, in 1979, a former Chicago cop -- a devout and conservative family man -- walked into a Soviet business in New York that was famously a front for Cold War intelligence operatives. Robert Hanssen, who’d jumped from the Windy City police force to the FBI just three years earlier, offered to hand over top-secret details to the GRU, the Soviet military intelligence organization.

For money.

His information was good -- so good that it would eventually lead to the executions of at least three US assets. It cemented a ruthlessly efficient, 22-year relationship between Hanssen and his handlers, “possibly the worst intelligence disaster in US history,” according to the commission later established to investigate it.

At the centre of the shocking betrayal was a man who seemed woven from the straight-laced fabric of counterintelligence backroomers, a man who rubbed colleagues the wrong way but seemed but seemed wholly devoted to the job and to his country. Hanssen lived in suburban Virginia with his wife and six children, socializing with the same best friend from high school, unfailingly attending Mass and even attempting to recruit others to join him in Opus Dei, an organization within the Catholic Church known for its airs of ultra-devotion and mystery.

That mystery, however, would pale in comparison to the furtive and deadly activities into which Hanssen plunged himself. He was finally found out in 2001, arrested in one of the suburban parks he’d so innocuously used as a drop location -- his law enforcement legacy forever in tatters, his family and friends horrified. Instead of enjoying retirement in picturesque Virginia, Hanssen was relegated to the Supermax in Florence, Colorado, locked away with the most dangerous and infamous of American criminals.

There, on Monday, he was found dead in his cell, an inglorious end to an ignominious life.

But Hanssen’s legacy of treason remains nearly unrivaled almost a quarter-century after his arrest.

His pedigree should have precluded him from his historic role of traitor, but it also perfectly placed him to pull it off. Raised in Chicago by a cop father, Hanssen first worked briefly as a CPA before joining the city’s police force -- and was sent straight to work in counterintelligence. He applied unsuccessfully to the NSA, then tried his hand with the FBI and made it; by 1979, he’d moved to New York with his young family and was working in the FBI’s counterintelligence division.

That’s when he made contact with the Soviets at the offices of Amtorg, a trading company established in 1924 by the USSR that was known for staffing members of the GRU.

“The information Hanssen turned over to the GRU was sensational, one of the most guarded secrets of both the FBI and the Central Intelligence Agency,” writes David Wise in his 2002 book Spy: The Inside Story of How the FBI’s Robert Hanssen Betrayed America. “Hanssen gave away no less than the identity of TOPHAT -- the most important US intelligence source inside the GRU.

“From his access to the FBI’s files, Hanssen was able to identify TOPHAT as the bureau’s code name for Dimitri Fedorovich Polyakov. At the time, Polyakov had been passing secrets to the United States for seventeen years. He was considered by Washington as an gent of supreme importance.

“Hanssen had a chilling reason for his action; he wanted to turn in Polyakov to the GRU before the Russian might learn his identity and reveal it to the FBI,” Wise wrote. “He had to be well aware that his information would probably result in TOPHAT’s execution -- that was the whole point.”

According to the 2002 Webster commission, which was formed to review FBI security programs following Hanssen’s devastating leaks, he would later claim that his motivation was economic: the pressure of supporting a growing family in New York City on an inadequate Bureau salary. His aim was to ‘get a little money’ from espionage and then ‘get out of it.’” During this initial period of espionage, he was paid about $20,000, it reported.

As Hanssen was spying from within the FBI, however, another Russian asset was spying from within the CIA -- Aldrich Ames. He, too, disclosed Polyakov’s identity, and TOPHAT was executed in 1986, the Webster commission wrote.

“Hanssen passed three batches of secrets to the GRU,” Mr Wise writes in Spy. “In his first approach, he disclosed that the FBI was bugging a Soviet residential complex. He also turned over a list of suspected Soviet intelligence officers ... He communicated with the GRU through encoded radio transmissions and through one-time pad, an unbreakable cipher system favored by the Russians. But of the various secrets Hanssen passed to the GRU, none compared to his betrayal of TOPHAT.”

By 1981, whether burdened by guilt or fear after being transferred to FBI headquarters in Washington DC, Hanssen cut off contact with the Soviets -- and confessed to his wife, attorney and a priest, the Webster commission reported.

Hanssen’s wife, Bonnie, knew the priest through Opus Dei, and the clergyman initially encouraged the FBI agent to turn himself in to authorities -- before calling Hanssen later to say that, instead, he could turn his ill-gotten money over to the Church, Wise writes. He told his wife he’d stopped spying, and she believed him, by all accounts.

But it wasn’t long before he was back at it.

In 1985, just nine days after he’d been transferred to a field supervisory position in the Soviet Counterintelligence Division in New York, “he wrote to a senior KGB intelligence operator to inform him that he would soon receive ‘a box of documents [containing] certain of the most sensitive and highly compartmented projects of the U.S. Intelligence Community,’” the commission reported.

“Hanssen asked for $100,000 in return for the documents (he would receive $50,000), and he warned that, ‘as a collection’ the documents pointed to him. Hanssen had particular concerns about his safety,” the commission continued.

“I must warn of certain risks to my security of which you may not be aware,” Hanssen wrote to the Soviets. “Your service has recently suffered some setbacks. I warn that Boris Yuzhin . . . , Mr. Sergey Motorin . . . and Mr. Valeriy Martynov . . . have been recruited by our ‘Special Services.’”

According to the commission, the other embedded spy -- Ames, of the CIA -- “gave the Soviets the same information about the three Soviet defectors around the same time as Hanssen. Two of the defectors were executed; the other was sentenced to fifteen years hard labor.”

Hanssen was accruing wealth and savvy, attempting to modernize Soviet spies’ ways, as he passed some 6,000 documents and 26 computer disks to his handlers, which eventually changed from GRU to KGB -- using aliases listed in an affidavit that include “Ramon Garcia” and “Jim Baker.”

The information he passed along “detailed eavesdropping techniques, helped to confirm the identity of Russian double agents, and spilled other secrets,” AP reported. “Officials also believed he tipped off Moscow to a secret tunnel the Americans built under the Soviet Embassy in Washington for eavesdropping.”

Hanssen is believed to have enriched himself by $1.4m -- and diversified his compensation as time wore on, lamenting to his handlers that it was hard to spend cash without arousing suspicion.

“Perhaps some diamonds as security to my children and some good will so that when the time comes, you will accept by [sic] senior services as a guest lecturer,” he wrote in one night, Wise reports in Spy.

“Because Hanssen had suggested a few diamonds might be welcome, the KGB obliged with one in September 1988,” Wise writes, detailing how a gem worth $24,720 was left for the FBI agent under a bridge in northern Virginia.

“A few months later, at Christmas, he received a second diamond valued at $17,748. For Hanssen, diamonds had the virtue of being small and therefor easily concealed,” Wise writes. “The cash that kept rolling in from Moscow was getting to be bulky and more difficult to hide, especially in a house that he shared with a wife and six children.”

Hanssen, meanwhile, was flying through the ranks of the FBI.

He left the Soviet Analytical Unit in May 1990 when he was promoted to the Bureau’s Inspection staff.

“Among other duties, Hanssen was charged with assisting in the review of FBI legal attaché offices in embassies across the globe. Hanssen’s Soviet handlers offered their congratulations on his promotion: ‘We wish You all the very best in Your life and career,’” the commission detailed. “Having assured Hanssen that their communications mechanisms would remain in place, the Soviets advised him: ‘[D]o Your new job, make Your trips, take Your time.’ Hanssen’s espionage continued after he joined the Inspection staff.

“At the end of his tour on the Inspection staff in July 1991, Hanssen became a program manager in the Soviet Operations Section of the Intelligence Division at Headquarters, a unit designed to counter Soviet espionage in the United States.”

He was, essentially, tasked with investigating himself -- ostensibly ferreting out traitors while committing the ultimate treason personally.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and Gorbachev’s resignation, Hanssen “decided to disengage from his espionage activity, he claims, because of feelings of guilt,” the commission reported.

He unsuccessfully and briefly tried to re-establish contact in 1993 but didn’t begin his third period of espionage until 1999, when he complained to the Russians about money problems.

“At the time, Hanssen was ‘running up credit card debt,’ some of which he had rolled into a home mortgage during two refinancings; some of his six children were in college; and ‘financial pressures’ were creating (in a phrase Hanssen adopted during a debriefing) an ‘atmosphere of desperation,” the commission reported. “Hanssen has claimed that his mortgage payments had grown so high that he ‘was losing money every month and the debt was growing.’ Consequently, he set a ‘financial goal’ for himself: obtain $100,000 from the Russians to pay down his debt.”

It was a suburban drop during this new spy stage that would ultimately be the agent’s undoing.

Ames had been unmasked as a spy in 1994, but US intelligence agencies were getting increasingly suspicious of, and angered by, their nemesis’ continued success at getting sensitive information. They couldn’t figure out where the leak was, and focus centred for years, wrongly, on a veteran CIA officer.

It would later turn out that officer had, at one point, lived on the same street as Hanssen and even attended the same church. But after the FBI came into possession of a recording of a 1986 conversation between a KGB operative and the suspected mole, it became clear that CIA veteran was not the speaker.

Analysts who’d worked with Hanssen not only recognized his voice but also a phrase he’d been known to use -- and the case broke wide open.

“In January 2001, Hanssen, who was then under suspicion, was transferred from the State Department to FBI Headquarters so that he could be closely monitored,” the commission reported. “Shortly thereafter, Hanssen would later claim, he came to believe that a tracking transmitter had been placed in his car. Despite these concerns, he went to another drop.”

That drop was on an ordinary winter Sunday in 2001. Hanssen had, just like on every other Sunday, attended Mass with his family on 18 February, after which he spent time with his best friend before dropping the Chicago man at the airport. Hanssen then drove to Foxstone Park in Vienna, just minutes from his home, where the unobtrusive 56-year-old -- now a grandfather -- hauled a plastic garbage bag sealed with clear tape from his car.

He took off for the park, then returned empty-handed -- only to find armed agents waiting to arrest him.

Hanssen had brought to the final drop an encrypted letter on a disk, addressed to “Dear Friends” and signed “Your friend, Ramon Garcia.”

It read: “I thank you for your assistance these many years. It seems, however, that my greatest utility has come to an end, and it is time to seclude myself from active service. . . . My hope is that, if you respond to this . . . message, you will have provided some sufficient means of re-contact . . . . If not, I will be in contact next year, same time same place. Perhaps the correlation of forces and circumstances will have improved.”

Later in 2001, Hanssen pleaded guilty to 15 counts of espionage and conspiracy in exchange for the government not seeking the death penalty. He was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole, a sentence that ended on Monday in Colorado when the 79-year-old was found unresponsive in his cell.

For a man whose life was built upon secrets -- keeping them, uncovering them, and selling them for profit -- Hanssen died with more than a few of his own. He told authorities following his arrest that his motivation had been financial; in a 2000 letter to the Russians, however, he “added, dubiously, that he had made his decision to become a spy as a teenager, inspired by the autobiography of Kim Philby, the Soviet mole inside British intelligence,” Wise writes in Spy.

He remained a man of mystery, living modestly while amassing ill-gotten wealth, immersing himself in religion and morality while selling fatal secrets that condemned and endangered other human lives. Many close to him found it immensely hard to reconcile the opposing aspects of Hanssen’s life following his shock arrest.

“I believe he was seriously religious and a serious spy,” his former FBI boss, Tom Burns, says in Spy. “Maybe a diagnosis would find him totally bipolar, able to segment different parts of his life. Parts that to all appearances were a contradiction.”

Another friend from the State Department, Ron Mlotek, puts it differently in the 2002 book.

“Although Mlotek did not doubt Hanssen’s faith, he thought he had answered the wrong calling,” Wise writes.

“’He should have been a priest,’ Mlotek said. ‘I think everyone would have been better off. The whole world would have been better off.’”