More than 60 years after the Starved Rock killings, a lawyer for the man convicted in what became one of the Chicago area’s most notorious murder cases says he has turned up a police report of an overheard conversation on a pay phone that he says proves Chester Weger wasn’t the killer.

Attorney Andy Hale says the police report is a “smoking gun” indicating that others, not Weger, killed three women from Riverside who’d been hiking in the popular state park 100 miles southwest of Chicago.

Hale says he found the report while poring over thousands of pages of police and court records in an effort to clear Weger’s name.

Weger, 83, was paroled two years ago after spending nearly six decades in prison following his conviction in the 1960 bludgeoning death of one of the hikers, Lillian Oetting, 50. Authorities said he also was suspected of killing Oetting’s friends Frances Murphy, 57, and Mildred Lindquist, 50.

The bodies were found in a canyon in the park.

In February 2020, the Illinois Prisoner Review Board paroled Weger — who had been the longest-serving inmate in the state prison system — saying he had been a model prisoner.

But that didn’t erase his conviction, and the courts haven’t cleared him.

Despite his conviction and having initially confessed, Weger has long said he didn’t kill anyone. Hale has been working on his behalf in an effort to get the courts to deem him innocent.

After Weger was released from prison, a LaSalle County judge agreed to Hale’s request to get DNA testing done on hair, cigarette butts and twine — used to tie the women’s hands — that were among the evidence gathered in the murder investigation.

Hale is hoping that the testing — which he says is expected to be completed in late July — will show Weger’s DNA isn’t on the items and might point to someone else as the killer.

Trying to find anything in the police and court records to cast doubt on Weger’s conviction, Hale says he found the two-page, April 20, 1960, police report earlier this year. It recounts an interview between two Illinois State Police investigators and the telephone operator. She told them about a conversation she said she accidentally overheard over a pay phone between two unknown men on March 21, 1960. That was five days after the women’s bodies were discovered.

The operator, Lois Zelensek, told the investigators that she hesitated to report the conversation because operators weren’t supposed to reveal anything they overheard.

“I even considered going to my priest for advice,” she told them, according to the police report.

Zelensek told the investigators she was about to tell the two men that the time they’d paid for on the call was up.

She said that’s when she heard one of the men, who was on an Aurora-area pay phone, say: “They sure have a big write-up on the murder case in tonight’s paper. You know, the kid has bloodstained overalls in the trunk of the car, and he’s getting a little anxious to know what he’s going to do with them. He’s afraid he’ll get caught.”

According to the operator, the other man on the call, who was on a phone in the LaSalle area, not far from the state park, responded, “We’ll tell him to get rid of them. Burn them.”

Zelensek told the police she thought that what she’d overheard was about the Starved Rock killings. And she said other parts of the conversation indicated that the LaSalle man was a car dealer.

She told the state troopers that, when she came on the line to tell the man from Aurora she needed to charge him extra for going over the time limit for their call, he was courteous.

Zelensek died in 2015.

Hale says the “write-up” the men were discussing that night in all likelihood would have been a March 21, 1960, story in the Chicago Daily Tribune — now the Chicago Tribune — that described evidence found in connection with the Starved Rock killings.

Hale says it’s clear from the operator’s story that the two men on the call knew the identity of the Starved Rock killer. And he says their conversation — describing an automobile trunk in which the killer supposedly stashed his bloody overalls — points away from Weger because he didn’t even own a car.

“I mean, wow, this Lois Zelensek interview is a bombshell, and this report is a smoking gun,” says Hale, who is doing a podcast on the Starved Rock killings. “This phone call is consistent with what I have been saying all along. That makes the most sense — a premeditated plan carried out by several people.”

News reports in 1960 said the police followed up on Zelensek’s tip. Investigators checked phone records for calls made that night and found that a call was placed at 9 p.m. from a pay phone outside an Aurora tavern owned by Glen Palmatier. According to the news reports, the call was made to the home of his brother William Palmatier in Peru, which borders LaSalle.

Interviewed by the police, the brothers denied any knowledge of a call from the tavern to William Palmatier’s home that night, according to the news reports.

The LaSalle County state’s attorney’s office arranged for Glen Palmatier to take a lie-detector test in Chicago and said it cleared him of suspicion. It’s unclear whether his brother took a similar test.

According to Hale, who says Weger didn’t have any connection to the brothers, a lie-detector test would have been a “ridiculous” way to check whether the brothers knew who killed the women.

“Get a search warrant, go to their house, their business, investigate,” he says. “I mean, you’re gonna have them take a lie-detector test? Oh, my God, I mean, what a ridiculous response. Can you believe that?

“This is, to me, clearly an attempt to cover this up.”

Hale says he thinks the authorities didn’t want to do a full-blown probe of the brothers because they were prominent citizens. Glen Palmatier was an Aurora liquor commissioner who ran unsuccessfully for mayor. William Palmatier was a used-car dealer who served as mayor of Peru.

“These aren’t some low-level, like, hoodlums,” Hale says. “These are connected bigwigs.”

The brothers died in the late 1960s, records show.

Hale says that one of the men being a car dealer fits with what Zelensek told the police about the men on the call having seemed at one point to be talking about the automobile business.

A few weeks after Glen Palmatier was cleared, the police took Weger into custody.

“Chester passed six lie-detector tests,” Hale says.

Weger has said the police coerced him into confessing to killing Oetting.

The office of Will County State’s Attorney James Glasgow, who has been appointed special prosecutor in Weger’s post-conviction case, didn’t respond to a request for comment about the Zelensek report. Glasgow opposed Hale’s request to have the DNA testing done.

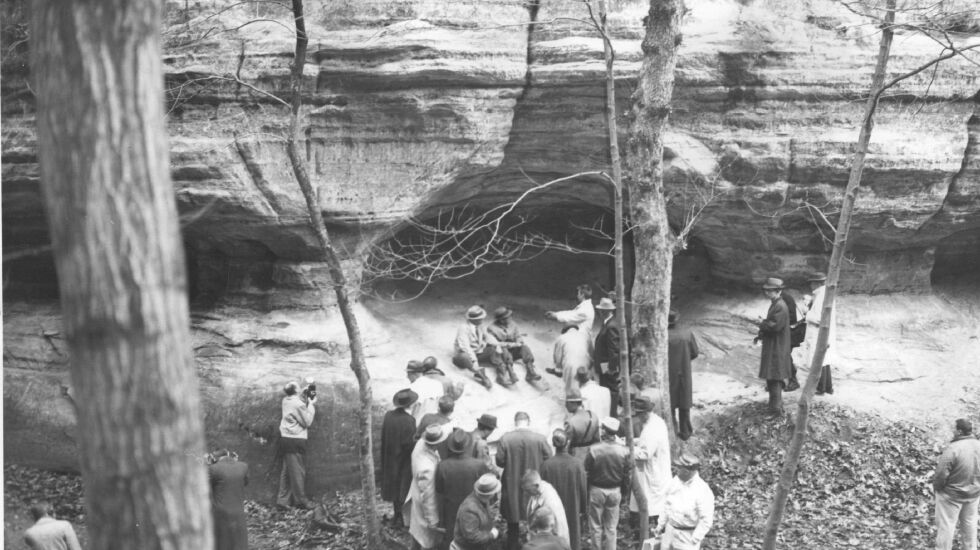

The remains of the three Riverside women were found March 16, 1960, in the park’s St. Louis Canyon. Each of the women had been beaten more than 100 times, and their bodies were unrecognizable.

All three women were married to corporate executives. Oetting’s husband George Oetting was a general supervisor of internal audits for Illinois Bell Telephone Company. Murphy’s husband Robert Murphy was a vice president and general counsel for BorgWarner Corporation. And Lindquist’s husband Robert Lindquist was a vice president of Harris Trust and Savings Bank.

Detectives said the cord that was used to bind their hands matched twine from a spool that was found in the kitchen of the Starved Rock Lodge, where Weger was a dishwasher.

For months, Weger, then 21, denied being involved in the killings.

Then, the police said, he confessed to beating the women to death with a frozen tree branch during a botched robbery attempt. And he took detectives to the state park to reenact the killings.

But then he recanted his confession.

His attorneys have pointed to evidence they say shows authorities told Weger he would be put to death in the electric chair if he didn’t confess. And they cast doubt on how Weger, who was a slender 5-feet, 8-inches tall, could have overpowered all three women.