Tensions are rising in the Democratic Republic of the Congo as it prepares for presidential and parliamentary elections while struggling to contain myriad armed groups wreaking havoc in the mineral-rich east.

The nation of about 100 million people is a battleground for more than 120 groups fighting for land and resources, some reportedly backed by or intervening in neighbouring countries, such as Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Uganda and Rwanda.

As election day approaches on December 20, government-aligned forces are battling the M23 group, which UN experts claim is backed by Rwanda. This comes on top of decades of war sparked by overspill from the Rwandan genocide in 1994. An estimated six million people have died since, with nearly seven million others displaced. Widespread insecurity has left more than a million without voter cards.

The African Union and the influential Catholic Church cast doubt on the results of the last poll in 2018, which saw incumbent Felix Tshisekedi emerge victorious over civil society favourite Martin Fayulu. Now, as the country once again prepares to vote, critics claim the president has the Independent National Electoral Commission in his pocket.

The country’s choice of president hangs on a single first-past-the-post ballot. Here’s the lowdown on those vying for the top job.

Who is Felix Tshisekedi?

Tshisekedi is the son of veteran opposition leader Etienne Tshisekedi, a towering figure in Congolese politics who founded the Union for Democracy and Social Progress.

He entered office in 2019 after 18 years of strongman rule by Joseph Kabila, who was himself catapulted to power after his father was assassinated at the height of the country’s civil war in 2001.

The new president was forced into an awkward power-sharing deal with Kabila, whose Common Front for Congo (FCC) party controlled two-thirds of parliament. But within two years, he had outmanoeuvred his foe, winning over FCC malcontents to a new coalition branded the Sacred Union of the Nation.

Much of his energy has since been invested in dismantling his predecessor’s power networks in the legislature, the judiciary and the military. But the Congolese are yet to feel the benefits, analysts say.

“The Congolese state is still riven with corruption and he hasn’t done anything visible or immediately obvious to tackle it,” says Richard Moncrieff, a consultant with the International Crisis Group.

Vast amounts of money have been pouring into state coffers, much of it from Katanga province, home to the country’s biggest reserves of cobalt – used for smartphone, computer and electric vehicle batteries. In all, the DRC’s vast mineral wealth – an estimated $24 trillion in untapped resources – is yet to trickle down to the people.

“That money’s getting lost, wasted or spent on the military,” says Moncrieff.

Nevertheless, with the opposition fragmented and help from vote-pulling allies like convicted embezzler Vital Kamerhe and former vice president Jean-Pierre Bemba, who was convicted and then acquitted of war crimes in the International Criminal Court, Tshisekedi stands a strong chance of being elected for a second five-year term.

Who are the main challengers?

At the time of writing, 21 opposition candidates are running. Aware of the dangers of splitting the vote, Tshisekedi’s rivals met in Pretoria last month to agree on a single candidate. The talks failed, but four have dropped out of the race to back Moise Katumbi, leader of Together for the Republic.

Barred from standing in the last election because of his mixed parentage – his father is a Greek-born Sephardic Jew – Katumbi is viewed as Tshisekedi’s main challenger. The wealthy businessman, who once governed the copper-rich Katanga, fled the country in 2016 after Kabila accused him of hiring mercenaries. Sentenced to three years in jail in absentia, he returned in 2019 after the charges were dropped.

The big question is whether other candidates will step down to back him, says Moncrieff. It seems unlikely that Fayulu, viewed by many in the country as the true winner of the last election, will be doing so.

The former oil executive, who leads the Engagement for Citizenship and Development Party, dropped threats to boycott the upcoming contest and remains a strong challenger. “Many preferred for me to stay away, the better to cheat,” he said in September.

However, analysts believe Denis Mukwege, another high-profile candidate, may be open to an alliance with Katumbi. The doctor known as “Dr Miracle” for his work in helping women raped by armed gangs in the war-torn east was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize in 2018.

But his humanitarian credentials may work against him, encouraging suspicions of foreign backing, thinks Jean-Claude Katende, president of the African Association for the Defence of Human Rights. “People think he’s a candidate of the West,” he says.

What’s the mood in the run-up to elections?

Katende sees Fayulu’s decision to return to the field as a positive sign for the country’s fragile democracy. However, freedom of expression is a major concern, with the government cracking down on journalists, rights activists and opposition candidates ahead of the ballot.

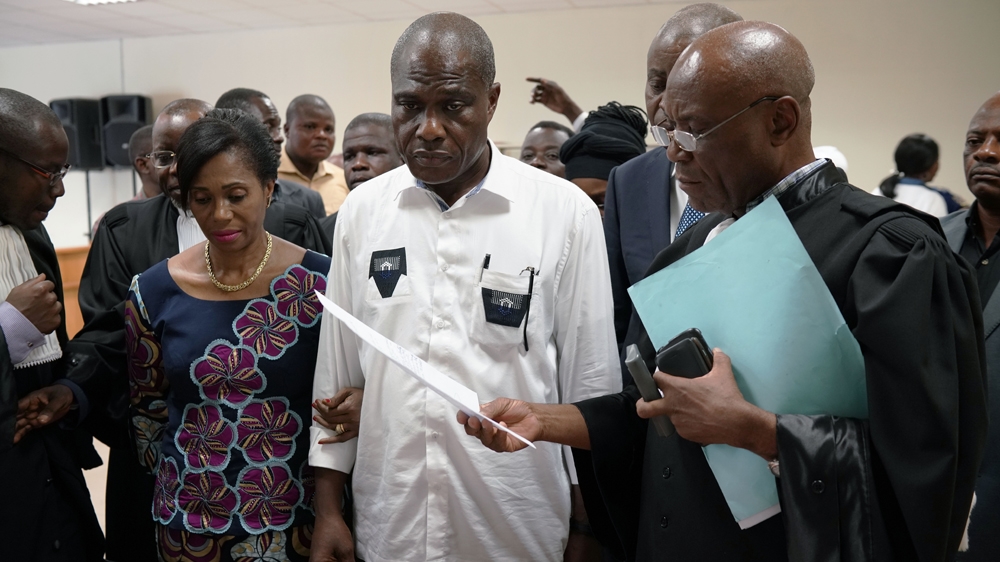

In September, Jean-Marc Kabund, a former Tshisekedi ally, was sentenced to seven years in jail for accusing the government of “mismanagement characterised by carelessness.” Kabund had recently set up a rival party called the Alliance for Change.

Concerns around transparency of the election have increased after the European Union announced the withdrawal of its team of observers in November.

Meanwhile, violence is continuing in the east after a ceasefire between the M23 and government-aligned militias broke down in April. Dormant for years, M23 launched an offensive in 2021, capturing swaths of mineral-rich territory. The group claims to be defending local Tutsis against Hutu militias and denies links to Rwanda.

The violence has provoked a local backlash against international peacekeepers. Tshisekedi has given the UN’s longstanding MONUSCO operation and East African Community forces their marching orders, banking on the Congolese military to see off aggression from the militias.

Heightened tensions with Rwanda, which accuses the DRC of providing refuge for instigators of the 1994 genocide that killed nearly a million Tutsis and moderate Hutus, are a key election theme.

“All the opponents accuse the others … of being soft on Rwanda,” says Moncrieff. “There’s a widespread feeling that Rwanda is backed by Western countries in order to pillage the resources of the Congo.”

Trapped amid all of this are the displaced, many of whom say they have no interest in voting or were unable to register to vote because of armed groups’ occupation in their villages.

What’s at the root of all this conflict?

The DRC’s woes go back a long way. Having already suffered monstrous abuses under 75 years of Belgian colonial rule – 10 million died during the hidden holocaust of the first 23 years – it has since been locked in a never-ending cycle of greed, exploitation and violence.

The post-colonial pattern was set in 1961, with the assassination of independence icon Patrice Lumumba in a Belgian-linked and US-backed plot that ushered in three decades of Western ally Joseph Mobutu, who ruled brutally.

By the mid-nineties, the Rwandan civil war between Hutus and Tutsis – its main ethnicities – had haemorrhaged over the border, turning the east into a war zone, with millions dying in the first and second Congo wars between 1996 and 2003.

Armed groups spawned in the wars and are now battling foreign-backed fighters in a toxic brew of ethnic intolerance and gamesmanship over mineral resources.

In a visit to Kinshasa this year, Pope Francis denounced the “poison of greed” driving conflict in the region, condemning “terrible forms of exploitation, unworthy of humanity”.

As the elections approach, the Congolese are once again uncertain if true peace and progress are on the cards this time.

“Personally, I don’t see any candidate embodying the change that Congolese people want,” says Katende.