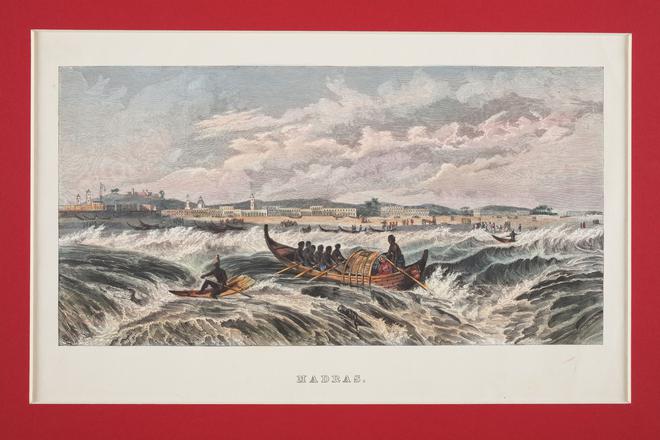

The porous nature of the Coromandel Coast has, for centuries, allowed it to absorb influences from across the world, either through trade or colonial conquests. Early maps show us that the region was the site of frenetic activity. In one such document, circa 1733 — part of digital archive Sarmaya’s collection — we see the Bay of Bengal shoreline dotted with the flags of no fewer than five colonial empires: the British, Portuguese, Dutch, Danish and French. Even older than the colonial legacies are those forged by its enterprising trading and fishing communities

Among them, coastal Muslims are identified by British anthropologists Caroline and Filippo Osella as having a greater openness towards new trends in food. In their book, Food, Memory and Community: Kerala as both ‘Indian Ocean’ Zone and as Agricultural Homeland, they write: “The whole Hindu domestic anxiety about the provenance of food stuffs, about caste purity and food ‘quality’ [in the tri gunas sense], about observing social hierarchies in feeding and serving, all mitigate against either culinary cosmopolitanism or a culture of domestic based hospitality and commensality. All this stands in sharp contrast to Muslim practices.”

This felt true to me, in my childhood in Tamil Nadu’s littoral lands and my family of sea-faring traders. Growing up in the coastal town of Kayalpatnam, I recall my grandmother’s term for condensed milk: ‘Edachi mark paal’. ‘Edachi’ is the Tamil caste name for those who work cattle — in other words, ‘milkmaid’! She was introduced to the Nestle dairy brand in the 1940s, before it became an Indian pantry staple, when her father brought home tins from his frequent trips to Colombo. Thanks to their trading background, coastal Muslims enjoyed a familiarity with the global commodities flowing through the Indian Ocean’s commercial arteries.

Regardless of their faith, the people of the Coromandel Coast have developed a multi-cultural palate through centuries of contact with colonial traders and merchants from the Persian Gulf, Red Sea, East Africa and the rest of Asia. This is most obvious when we sit down to eat — not just in Kayalpatnam, but across coastal Tamil Nadu. Our daily fare effortlessly folds in influences from Indonesia to Sri Lanka, and from Ethiopia to the Netherlands.

Kuzhi paniyaram for breakfast

In the case of the widely-loved kuzhi paniyaram, we see the foreign influence not of a recipe but a clever little kitchen implement. Inspired by the poffertjes pan introduced to these parts by the Dutch, the paniyarrakal or appe pan is a versatile tool.

The original featured three semi-circular indentations made to fry the mini pancakes it is named for. But we’ve significantly expanded its scope to make everything from savoury paniyarams to sweet unniappams, and all the other gunta (Telugu), guliyappa (Kannada) and appe (Marathi) in between. It’s no surprise that today kuzhi paniyarams are closely associated with Chettinad cuisine; the Chettiars enjoyed long historical trade ties with the Dutch East Indies.

Thakkadi for Sunday lunch

A guarded recipe among the Tamil-speaking Muslims of the Coromandel Coast and Sri Lanka, thakkadi is a one-pot dish that looks a lot like pasta. Steamed rice dumplings are steeped in a runny broth of spicy condiments, pandan leaves, coconut milk and goat’s brain — nose-to-tail eating being a way of life in these parts. It’s usually cooked after Bakrid when offal overruns kitchen counters and freezers in towns like mine. Given the Coast’s proximity to Sri Lanka, it’s not surprising that many culinary traditions like the thakkadi have made their way across the sea.

Thengai buns for tea

Covered in see-through wrappers and heaped on bakery counters across the coast, thengai buns are just the thing to dunk into a hot cup of tea at the end of a long day. These are thin discs of leavened bread stuffed to bursting with sweet, grated coconut and tutti-frutti (candied fruits); elsewhere in southern India, they have more poetic names such as dil-pasand and dil-khush. Culinary historians believe the technique of leavened bread-making arrived in the subcontinent with the Portuguese. Thengai bun mixes yet another colonial influence to serve up a tropical take on the British mince-pie. Thanks to their exposure to European trade, cities like Thoothukudi in the southern districts of the Coromandel Coast have a thriving and visible bakery culture. The Portuguese word for leavened bread ‘bao’ has acquired the twang of Tamil to become ‘paan’, as my grandmother’s generation calls it.

Koliappam for family dinner

During perunaals (Eids), the Tamil Muslims of the coast make lacy, translucent crêpes to eat with coconut curries. The koliappam has less in common with the local palappam and more with a faraway cousin: the East African injera. Made from rice flour, coconut milk, eggs and salt, the batter is poured onto a non-stick pan, which is swirled quickly to form a thin layer. In the home of the dosai and similar savoury crepes, the popularity of koliappam is evidence of the coastal Tamil people’s insatiable appetite for novelty and openness to cultures far and wide.

Dodol for dessert

Even the resolute among us will find their pace slowing as they pass the Sellakani store in Keelakarai. On the counter are neat stacks of small tubs containing an irresistibly sticky confection. Dodol is a toffee-like sweet made from rice flour, tapioca balls, coconut milk and palmyra jaggery, not to mention lavish quantities of elbow grease.

It’s a favourite with the region’s diasporic community who rely on friends and family to send them a steady supply of this local delicacy. While the dish is Indonesian in origin, it actually arrived in Keelakarai from Sri Lanka in the mid-20th century. A resident, Fathima, tasted dodol on a trip to the island nation and on her return, she taught her sister Jeilani Beevi the recipe. Jeilani’s son now carries on the tradition at Sellakani.

The first in a series of columns by sarmaya.in, a digital archive of India’s diverse histories and artistic traditions.