Last year, on Feb. 15, the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department issued a press release announcing that a 67-year-old man named Gilbert Gonzalo Gil had been found dead in his cell at Vista Detention Facility the previous night, 16 or so hours after he was booked for being under the influence of a controlled substance. Gil’s exact cause of death, the statement explained, would be disclosed “pending laboratory results and further evaluation,” though it was suggestively noted that he had tested positive for COVID-19 before dying and that an autopsy conducted by the county medical examiner’s office had revealed traces of methamphetamine in his system.

To Gil’s daughter, 41-year-old Jennifer Schmidt, the press release raised far more questions than it answered. She had reason to doubt that he’d died of COVID-19, having seen her father symptom-free hours before his arrest. Furthermore, she believed that the erratic behavior leading to his arrest—a concerned family member had dialed 911 for medical help; instead, cops showed up and hauled Gil out of his bedroom in handcuffs—stemmed from complications of his hyperglycemia and dementia, not drug use. “I was confused,” she says. “I didn’t believe my dad just went to jail and died.”

That feeling intensified days later when Schmidt visited the county crematorium to see her father’s body and noticed a “big, red mark” stretching from his forehead up into his wispy, silver hair. “My gut told me that something wasn’t right,” she says.

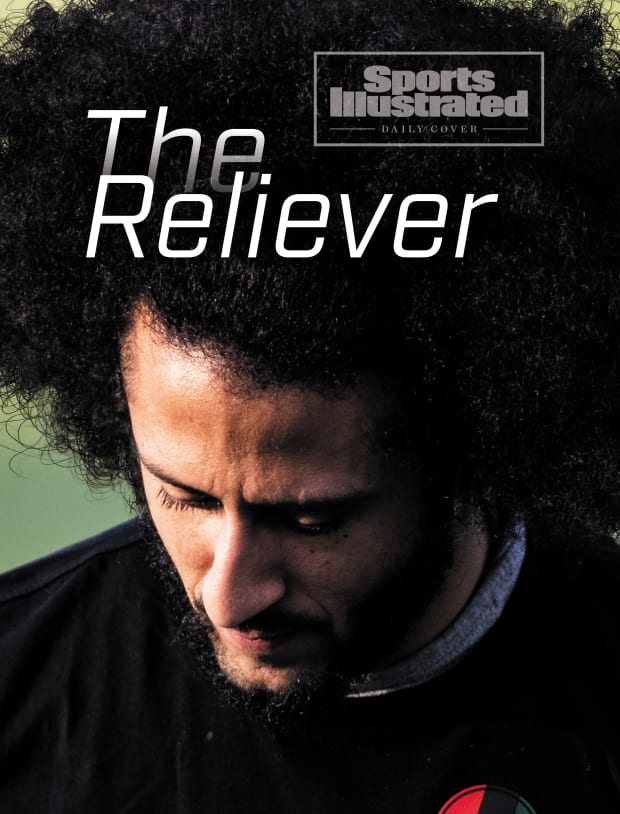

Carmen Mandato/Getty Images

Looking for help, grasping for advice, Schmidt found that her best next step was to hire a forensic pathologist who could perform a second autopsy on her father, providing an expert opinion independent of the criminal legal system. But, Schmidt says, “I just couldn’t afford it. I was discouraged. I was like: I’m gonna have to depend on what the county says.”

The following week, though, Schmidt saw a news segment on TV covering the launch of a new charity providing free autopsies after police-related and in-custody deaths. Surprised as Schmidt was by this serendipitous timing, she was more taken aback when she learned that the Know Your Rights Camp Autopsy Initiative was the brainchild of an NFL quarterback turned activist whom she once regarded with skepticism.

Left with no other options in her quest for clarity around her father’s death, Schmidt visited the Initiative’s nascent website. She clicked on an autopsy request form, typed out a summary of her father’s death and hit submit, hoping for the best but expecting much less.

“I thought it would have to be a high-profile case for them to call me back,” Schmidt says. “I was like: Colin Kaepernick? Yeah, right. Never going to help me.”

When the Chiefs and the Eagles finally take the field at Super Bowl LVII, a decade will have passed since Kaepernick appeared on the sport’s biggest stage. Then in his third year out of Nevada, and his first as the 49ers’ starting QB, he passed for 302 yards and a touchdown, adding 62 yards and another score on his own feet, in a 34–31 loss to the Ravens that seemed to herald the coming of the sport’s next great star. “Kaepernick showed exactly how dynamic—and how rare—a quarterback like him has become,” one columnist wrote from the Superdome.

But that would be Kaepernick’s professional peak. In 2016, he began kneeling during the national anthem, in protest, he said, of racial inequality and police brutality. Unsigned as a free agent the following offseason, he never played another professional snap. (In February ’19 he settled for an undisclosed amount—alongside his co-plaintiff, safety Eric Reid—in a collusion grievance against the NFL and its owners.)

Late in 2016, sometime around his last game, Kaepernick connected through mutual friends with Ben Meiselas, an attorney who at the time was litigating, and whose law firm had paid for private autopsies surrounding several police-related-death lawsuits in Southern California. “We got to know each other very well, and one thing we’d talk about is that in lots of these cases the sheriff is also the coroner,” Meiselas says. “So, you end up with findings incongruent with the actual cause of death, and families who aren’t given the truth and explanations.”

The plight of those families resonated with Kaepernick, planting the seed for what the Autopsy Initiative would ultimately become. (“He was like: How could that possibly be? They don’t even learn what happened?” Meiselas recalls.) But the Initiative would remain just an idea, as Kaepernick channeled his activism energy elsewhere for the next few years, hosting educational events for young Black and Brown people through his Know Your Rights Camp charity and donating more than $1 million to organizations serving oppressed communities.

Ezra Shaw/Getty Images

In June 2020, the idea of independent autopsies entered the national spotlight after two pathologists hired by the family of George Floyd determined that the Minneapolis resident had been suffocated when officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck. That report contradicted the county medical examiner’s preliminary autopsy, which “revealed no physical findings” to “support a diagnosis of traumatic asphyxia or strangulation.”

That summer, Meiselas and Kaepernick, along with Kaepernick’s longtime girlfriend, Nessa Diab, began meeting on the phone for hours each week, sketching out how they might be able to provide clarity to families in similar situations. “We’d always been talking about it,” Meiselas says. Now, though, “the timing was right.”

Before the Autopsy Initiative officially kicked off, says Kaepernick, now 35, there was “significant time for truly learning the issues and challenges” of the existing autopsy system. Three factors stand out to him in particular. First: “the bias that could arise” in state-issued reports, a possible function of the well-documented coziness that commonly exists between police and medical examiners (assuming they’re not the same person). Second: “We learned of the use of faulty forensics,” says Kaepernick, referring to how slipshod pathology can lead to critical details going undocumented. And third: They weighed the significant “financial burden” that a private autopsy can place on friends or loved ones, with costs typically ranging between $10,000 and $15,000, depending on how—and how far—a body needs to be moved.

Overcoming that economic hurdle would be easy enough, with Kaepernick vowing to cover everything through charitable contributions made to his organization. Ensuring that the aggrieved also got “transparency, objectivity, compassion and understanding,” as Kaepernick describes the Initiative’s mission, would take longer. “We spent probably 18 months analyzing every permutation of what could happen,” Meiselas says. “What happens with the body? What protocols do you set for the pathologist? How is the data harbored and communicated with the family?” Asked what stands out about Kaepernick’s participation in this phase of planning, Meiselas replies: “How careful he was, the painstaking attention to detail.”

Nicole Martin was hired in August 2021 to become the Initiative’s legal program director and its first full-time employee, and as early as her second remote job interview she took notice of this level of diligence. “Colin was on [that call], and I had no idea that he’d even be present,” says Martin, 28. As an undergraduate at UC Riverside, Martin had devoted her senior thesis to analyzing the connection between race and police brutality. But she’d never realized the importance that a second autopsy could play until she heard Kaepernick articulate his vision for the Initiative and his motivations behind it. “Because police-related deaths continue to be widespread, he wants to provide a sense of relief to families,” Martin says.

Agustin Paullier/AFP/Getty Images

It was for similar reasons that Roger Mitchell, the chair of pathology at Howard University, says he eagerly accepted an invitation to join the Initiative’s panel of board-certified forensic pathologists—once, that is, he recovered from the shock of discovering such a program existed at all. “Subsidizing autopsies for those who died in connection with the criminal legal system,” says Mitchell, 48, “that doesn’t exist anywhere else.”

A former high school lineman himself, Mitchell says he’s always been a fan of Kaepernick—“both of his athletic career and his career in advocacy.” So what does Mitchell make of the former QB’s foray into the relatively niche world of independent autopsies? “I think he has observed a gap and led by his heart, understanding what is needed to support families,” he says. “It’s a link to his inclination to take a knee, right?”

Jennifer Schmidt never expected any sort of response after she submitted her request to Kaepernick’s Autopsy Initiative last February. In reality, her inbox pinged with an email from Martin that same day. It wasn’t much longer before her father’s casketed body was loaded onto a plane in San Diego, flown halfway across the country to Omaha, and placed on a medical exam table in front of Nebraska Institute of Forensic Science executive director Matthias Okoye, another one of the Initiative panel’s pathologists.

At the time, the independent autopsy performed on Gilbert Gonzalo Gil last March marked the seventh to be paid for by the Initiative. To date, less than a year after its launch, the Initiative has provided 42 autopsies tied to police-related- or in-custody-death cases, spanning 15 states.

In each instance, a form and a series of questions (about how the victim is believed to have died, where the body is located …) are relayed to an Initiative pathologist, who determines the likelihood of pronouncing an official cause of death. And “if the pathologist says yes,” explains Martin, “we match the pathologist with the victim’s family.” All the while, Kaepernick remains hands-on: He takes updates at weekly staff meetings, occasionally speaks to pathologists, and personally reviews and approves each case. “He’s involved in every layer, every level,” Meiselas says.

Once a case is accepted by the Initiative, Martin typically coordinates transportation through the pathologist and funeral home directors on both ends—but this isn’t always seamless. “There can be issues obtaining permits, because each state has different transport laws,” Martin says. “There are delays from the coroner’s office in providing the death certificate to the funeral homes.” Other obstacles are less bureaucratic, some more based on personal beliefs. “We’ve had funeral homes resist working with us—and one deny us—because of our organization and who [is involved],” Martin says.

Courtesy of Jennifer Schmidt

As a protection against bias, Initiative pathologists aren’t allowed access to any existing initial findings from the local medical examiner’s office. “We don’t have much history. We’re going in just looking for evidence of injury or disease, and to document what is found,” says Mitchell, who has performed more than a dozen such procedures, all at a D.C. funeral home, on behalf of the Initiative. “The majority of times, we’re going to find exactly what the first autopsy found.” But not always.

In one of the earliest Initiative-funded cases, the family of an inmate who had been discovered dead in his jail cell was told that an autopsy was performed by the county—but the Initiative’s pathologist found, curiously, no signs of surgical cuts on the body. “The family was flat-out lied to,” Martin says. In another case, involving a man who was shot and killed by police during an attempted arrest, an Initiative pathologist discovered a bullet that the local coroner’s office had failed to remove. In others, Mitchell says, “there are certain technical procedures that should’ve been performed on the body, that weren’t.”

Those types of errors can be chalked up to the “faulty forensics” Kaepernick describes. But an independent autopsy can also reveal far darker discrepancies, like in the cause of death itself.

Norico Martinez was deep-cleaning her home in Greeley, Colo., an hour north of Denver, one day early last October when she received an email with a PDF attachment labeled “Final Autopsy Report.” Trembling with dread, Martinez, 36, eventually calmed herself down enough to comb through the official findings of the Omaha pathologist, Okoye, who had performed an independent autopsy on her mother, Lisa, through Kaepernick’s program. “It was mind-blowing,” Norico says. “From the first autopsy to the second, they were night and day.”

Five months earlier, Norico received a call and was alerted that Lisa, then 55, had been found unresponsive in the Weld County Jail cell where she was being held for money laundering and possession of a controlled substance. Authorities transported Lisa to a nearby hospital, where she was placed on assisted breathing just long enough for Norico and other family members to arrive and say goodbye. The county coroner later deemed Lisa’s death to be of natural causes, attributed to “complications of combined bronchopneumonia and dehydration,” according to records—but Norico suspected otherwise, having observed in the ICU a series of cuts and bruises on the left side of her mother’s body. Which led her online, where she found the Autopsy Initiative in a Google search.

And now here was the confirmation: “In view of the clinical history and the findings,” the independent autopsy read, “the cause of death is asphyxia by manual strangulation. … The manner of death is ruled homicide.” (There are five “manners” used by forensic pathologists to categorize a death: natural, accident, suicide, homicide and undetermined.)

The revelation hit Norico hard. “It worsened my depression,” she says. “I battle every day, just to get out of bed. It’s the worst thing I’ve ever faced.” Yet, as time passed, she also felt that the finding hardened her resolve to “keep pushing,” not only for the sake of her own three children, but for Lisa’s memory, too.

Courtesy of Norico Martinez

For many Initiative clients, the arrival of independent autopsy results can mark an end and a beginning. Because it can often take upward of six months, according to Martin, to obtain completed reports from local medical examiners (a critical precursor to an independent pathologist being able to issue their own final opinion), only four of the Initiative’s 42 cases so far can be considered fully completed. But even an independent pathologist’s preliminary finding, which the Initiative shares with a client as soon as it is available, can provide enough of a road map to take legal action. “We have a distinct purpose in providing the second autopsies, but they also give attorneys a chance to know if there’s a civil rights case to pursue,” says Martin.

In one such case, a $100 million lawsuit filed by the family of 23-year-old Robert Adams against the city of San Bernardino, Calif., late last year, a Kaepernick-funded autopsy confirmed what security cameras had captured on video: that police shot and killed Adams seven times in his back and side as he was fleeing from them in a parking lot. Here, the value of the independent autopsy was less in contradicting the state’s position, that Adams was armed and intended to take cover behind nearby cars to return fire, and more in providing expert documentation of the truth about Adams’s fatal injuries. “It’s my understanding that the [city] coroner’s office is refusing to produce the initial autopsy report to us, even though we’ve requested it multiple times,” says Bradley Gage, an attorney for Adams’s family. “The more evidence that we have of wrongdoing, the bigger the outcry should be from the public for justice for Rob.” (The San Bernardino City Police Department did not respond to a request for comment.)

Norico Martinez, meanwhile, was struggling to find a lawyer to take her mother’s case, until Initiative staff provided several recommendations in her area; now she says an attorney is gathering medical records and other documents in preparation for potential litigation. “I’m gonna fight with everything I have in me,” Norico says, “until I have justice for her.” (Beyond confirming that an autopsy has been completed by the county coroner, a public information officer for Weld County declined to comment on Lisa’s case.)

Schmidt began to head down the same road in April after receiving the Initiative’s early findings about her father’s death. There Okoye ruled out not only COVID-19, drugs and alcohol as potential causes, but also cardiac arrest and any other organ failure. Instead, Okoye concluded—in part based on the significant bruising up and down Gil’s body, and the fact that his fingertips and toes had turned blue, from a lack of oxygen—that death had resulted from asphyxiation. In August, Schmidt’s lawyer filed a tort claim against the county of San Diego, summarizing Okoye’s findings and opining: “This is akin to how George Floyd died.” (In response to a request for comment, a rep for the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department shared the text of the Feb. 15 release announcing Gil’s in-custody death. According to records, the county medical examiner’s office eventually classified Gil’s death as “accident,” attributing it to hypertensive cardiovascular disease; the medical examiner’s office did not respond to a request for comment.)

Although Schmidt’s claim was rejected by the county, she says she plans to file a lawsuit once Okoye’s final report is issued. But no matter what future compensation her case might bring, she says the Autopsy Initiative has already provided her with something perhaps more valuable: the “sense that I’m not crazy—that something happened that wasn’t supposed to happen.”

Seth Herald/AFP/Getty Images

A lifelong Steelers fan who still keeps her father’s beloved Lynn Swann jersey in her closet, Schmidt describes growing “angry” at Kaepernick when he first took a knee before a game. “I was like, ‘How can you not be proud to be an American?’” she says. Now she believes she understands his motivations in a way she never thought possible. “Yes, [this has] changed my opinion,” she says. “If it wasn’t for the Autopsy Initiative, my dad would just be written off as a COVID- or a drug-related death, like what [the sheriff’s department] told the media.”

For the Initiative, the work isn’t stopping anytime soon. “As police-related deaths continue to persist, our program is critically needed,” Kaepernick says. In 2022, there were at least 1,176 police killings in the U.S., a national record, according to one analysis. And two weeks ago the preliminary results of an independent autopsy (unrelated to the Initiative) found that a 29-year-old Memphis man named Tyre Nichols had suffered “extensive bleeding caused by a severe beating” before dying at the hands of five police officers, an incident that their department’s Twitter account had initially downplayed as “a confrontation [that] occurred,” after which “the suspect complained of having a shortness of breath.”

Kaepernick hasn’t spoken personally to any of the families who have worked with the Initiative, preferring to keep a distance while its painstakingly crafted protocols unfold. But Martin says she receives thank-you emails addressed to the former QB “all the time.” (Example: “You lend me so much wind beneath my wings to continue this pursuit of justice for our beloved son.”) She forwards each one along, so that Kaepernick, too, can know what the service means to the people it serves.

“They gave me closure,” Norico Martinez says. “They answered questions for me that could’ve easily been unanswered. But they also opened a new book.”