Concerns about fuel poverty and people not being able to heat their homes adequately are not new in the UK, but these worries have been heightened by significant increases in energy costs and the cost-of-living crisis. And as winter approaches, things are about to get a lot worse.

Despite a relatively mild climate, the UK has higher levels of excess winter deaths – deaths associated with cold weather – than many colder countries. This greater exposure to cold, despite milder weather, is related to poor housing quality, the high cost of heating homes and poverty.

We know quite a lot about how living in a home that you can’t keep warm enough affects your physical health. Colder temperatures suppress the immune system, for example. But we know relatively little about the effects on mental health. Our new research shows that living in a cold home is a significant mental health risk.

Living in a cold home can affect your mental health in several ways. For many, heating costs are a source of stress and financial strain. Not being able to keep your home and family comfortably warm reduces feelings of control and autonomy over your environment. People who are unable to heat their home often adopt coping mechanisms that limit socialising – for example, not inviting friends over and going to bed early to keep warm. And many people are just worn down by the drudgery of a whole winter of being uncomfortably cold.

Using data from a large representative sample of adults in the UK, we followed people over many years and tracked the effect of being unable to keep your home warm on mental health.

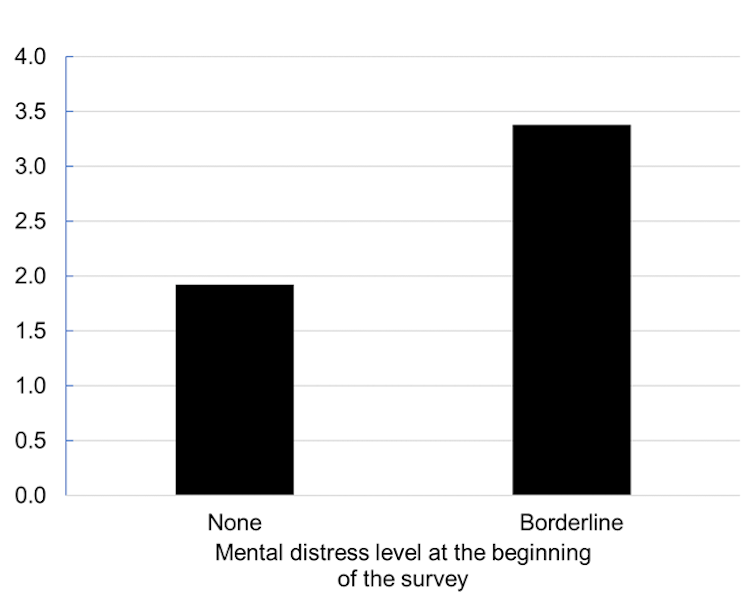

When people’s homes became cold, their risk of severe mental distress significantly increased. For people who previously had no mental health problems, the odds of severe mental distress doubled when they had a cold home, while for those who had some (but not severe) mental health symptoms, the risk tripled (see chart below). We found these effects even after taking into account many other factors associated with mental health, including income.

Odds of reporting severe mental distress following transition into cold housing compared to those who remained in warm homes

Sadly, the risk of living in a cold home differs greatly across the UK population. Lone parents and people who are unemployed or long-term sick are much more likely to live in cold homes. There is also significant inequality across ethnic groups – more than 12% of black people live in cold homes compared with under 6% of white British people, for example. Those who rent rather than own their home are also far more likely to live in cold homes, for social renters this is despite the, on average, higher quality andefficiency of social rented homes.

Putting on another jumper won’t be enough to get many in the UK through the coming winter. And mental health distress is just one consequence. Cold homes cause issues with significant personal and societal costs – from individual health effects to the increased pressure on the NHS, as well as broader economic loss due to missed work. Rishi Sunak’s new government needs to help people live in adequately warm homes this winter. But how?

The older age of housing in the UK is heavily implicated in the UK’s high levels of cold. Support for energy efficiency improvements is therefore a possible means of reducing cold homes. This will also mean tackling the so-called “split incentive” in the private rented sector, which houses a significant proportion of households. The split incentive refers to the challenge of the benefits of improvements not being experienced by the property owners but by tenants, reducing the incentive for owners to invest. This results in poorer quality and more expensive homes for renters.

Heat or eat? Most can’t afford either

The high proportion of cold homes in the social housing sector – despite having the best average energy efficiency due to insulation and building types (flats) – shows that energy efficiency improvements alone will not eliminate cold. Incomes in the UK are falling. Benefit levels are painfully low and worsened by policies including the benefit cap, two-child limit and sanctions. Years of cuts and below inflation rises mean that the term “heat or eat”, used to describe difficult spending decisions for low-income households, is now out of date, as many can afford neither.

The combination of low household incomes with surging energy costs has created devastating pressure on household budgets. While the energy cap has limited energy cost increases below the worst estimates, energy bills have still more than doubled in the past year. And prepayment meters mean that those the with the least end up paying the most.

There are, therefore, many areas for potential government intervention, and clear evidence that failing to intervene will cause harm to health.

Amy Clair receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Emma Baker receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC), the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), and the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) . She holds a board position for Habitat for Humanity SA.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.